Why Literature is Wokewashed

We used to go to great writers for the truth. And it's still there.

What follows are some thoughts aimed at helping humanities students, primarily as an antidote to the woke-washing of literature. Even if all they do is arouse curiosity, they will have succeeded.

Don't take it as a matter of course, but as a remarkable fact, that pictures and fictitious narratives give us pleasure, occupy our minds.

- Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations.

What is literature?

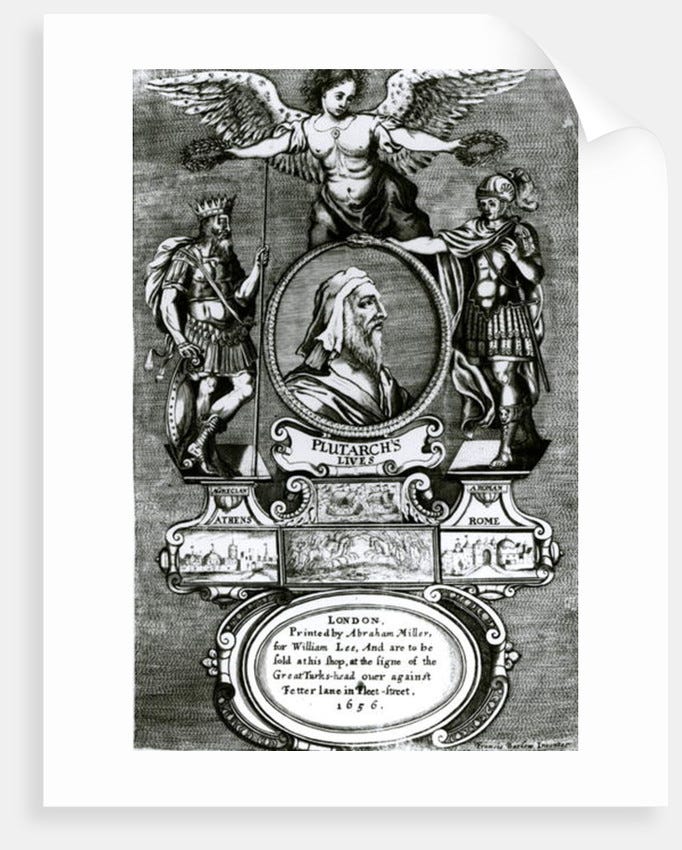

By far the best book on this is Wellek’s Theory of Literature, but a brief outline will be useful for clarity:

The term litteratura, which comes from littera, “letters” in Latin, was called by Quintilian a “translation of the Greek grammatike”: a knowledge of reading and writing.

Cicero, however, spoke of Julius Caesar as having littaratura in a list of his qualities, which includes “good sense, memory, reflexion and diligence”: literary culture.

In the second century, Tertullian and Cassian, for the first time, used the term to contrast secular literature with scriptura, pagan with Christian literature: a body of writing.

In Rome, the term litterae was prevalent, meaning the study of the arts and letters of the Greeks as far as they represented the Greek idea of man.

In the Middle Ages, Literatus or literator meant anybody acquainted with the art of reading and writing.

With the Renaissance, a clear consciousness of a new secular literature emerged and with it the terms litterae humanae, lettres humains, bonnes lettres, or as late as in Dryden, “good letters” (1692).

By that time, the term “literature” had re-emerged in the sense of a knowledge of literature, of literary culture. Thus Boswell refers to Giuseppe Baretti as an “Italian of considerable literature.”

E. R. Curtius’ definition in European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, then, is neither too narrow nor too broad: literature, he said, is ‘the great intellectual and spiritual tradition of Western culture as given form in language’.

Why study it?

Typical answers to this miss the point, e.g., ‘to improve your vocabulary’, ‘to improve your critical thinking skills’. Those are mere byproducts.

For as long as there have been people, literature has been studied, even when it was only oral, because it’s interesting, using that word in its original sense of ‘it matters’. The etymology of ‘interest’ is illuminating here: from the noun use of the Latin interest "it is of importance, it makes a difference," third person singular present of interresse "to concern, make a difference, be of importance," literally "to be between," from inter "between" + esse "to be".

It matters for many reasons:

Literature is about the greatest wonder in the visible universe: man.

It is a record of his highest activity: the pursuit of Truth, Goodness and Beauty.

It does so using language – the tool of his highest faculty, the intellect.

It tends to use language in the ways in which the intellect tends to grasp the highest concepts: metaphor, simile, symbolism, analogy. As Petrarch asked, 'what is theology, if not poetry about God?'

Indeed, when considering what subjects should be studied, Dr. Johnson said, in his Life of Milton,

…the truth is that the knowledge of external nature, and the sciences which that knowledge requires or includes, are not the great or the frequent business of the human mind…[W]e are perpetually moralists, but we are geometricians only by chance…Those authors, therefore, are to be read at schools that supply most axioms of prudence, most principles of moral truth, and most materials for conversation; and these purposes are best served by poets, orators, and historians.

Important caveats

Literature in English has been a respectable university subject for barely a century. The scholar of Scottish and English ballads Francis James Child was appointed to the first chair in English at Harvard in 1876; the English honors degree was not established at Oxford until 1894.

Although it can help show you good and evil, it can’t make you a good person. For an attack on the view that it can, see George Steiner's stimulating essay 'To Civilise Our Gentlemen' in Language and Silence. Having lost confidence in Matthew Arnold’s idea of literature as a secular scripture capable of inculcating virtue, many people talk of the death of literature.

But literature in his sense was stillborn. As Cardinal Newman quipped, trying to subdue the passions of man with art is like trying to leash an ogre with a noodle.

Although Matthew Arnold was wrong to think literature could make people good by inculcating virtue, it is likely, however, to at least awaken the moral and spiritual sense of its students. Accordingly, the Jesuits thought the classics could be used as ‘hooks to catch souls’. The experience of many bears this out. Reading The Brothers Karamazov, Shakespeare’s tragedies or Moby-Dick, for example, can be intellectually and spiritually harrowing.

Ultimately, as W. J. Bate put it in his excellent article ‘The Crisis in English Studies’, the subject matter of literature is unrivalled:

it aims at giving the whole experience of life – historical movements, the individual's dilemmas in the choice of values, original sin, and the highest hopes and visions of mankind.

And, uniquely, it does so by making one bump up against concretely real people, things, and events in story, as in life. In that sense, it brings philosophy to life. As Schopenhauer said, the artist does in the concrete what the philosopher does in the abstract.

How to study it?

Forget trendy ideas in education about 'learning to learn'. Think about how stupid that is for a moment. Before you could learn how to learn, you'd have to learn how to learn how to learn, generating an infinite regress, in which you'd learn nothing - as actually happens in most schools.

Endless energy goes into avoiding activities that are simple, hard and effective:

listen to people who know more about the subject you are learning than you do

read and summarise what you read to check you have grasped it

explore the limits of your understanding in writing

talk to other people who are at a similar stage in their understanding

These are unpopular with overpaid educational theorists because they aren’t sexy: they give little scope for initiating people into an Inner Ring of Learning. (Beware inner rings, as C.S. Lewis wisely warned.) And they are unpopular with lazy people because they are demanding.

But what did you expect? What did you want? Spinoza's insight, as inspiring as it is chastening, cannot be repeated too often: 'All things excellent are as difficult as they are rare'.

Basic Tips

Set yourself a small but manageable amount of reading of daily reading. When you find you can stick to it, increase it slightly.

‘Read not The Times, read the eternities.’ (Thoreau)

Look up unfamiliar words immediately. Write them in a vocabulary book. Review them regularly.

One of the best ways to improve your writing is to read it aloud.

Use pens of different colours for different sorts of annotation and underlining. Reading is active. Dr. Johnson’s books often fell apart.

Don’t feel the need to read the whole of every book you pick up.

Not every book you read needs to be the calibre of the Iliad.

Beyond the Basics

For a full treatment of going further, see A. D. Sertillanges’s The Intellectual Life. Here are some pointers:

Why are you reading demanding books? To say you’ve read them to appear cultured to impress people? No, you are forming your mind.

This will benefit from a plan, so focus on a small number of topics.

Write about them to develop your thoughts fully. When choosing a question to explore, make it controversial, specific and an either/or.

Engage with secondary literature; otherwise, you’re sparring without a partner.

Take pride in the essays that will be the finished product of this process. People have died for your freedom to read, think and write.

Advice on Style

To think clearly, write clearly. This is a moral matter, as Montaigne recognised:

Our understanding is conducted solely by means of the word: anyone who falsifies it betrays public society. It is the only tool by which we communicate our wishes and our thoughts; it is our soul’s interpreter: if we lack that, we can no longer hold together; we can no longer know each other. When words deceive us, it breaks all intercourse and loosens the bonds of our polity.

By contrast, have you noticed how incomprehensible postmodernist prose is? Consider this, for example, from Judith Butler, a Guggenheim Fellowship-winning professor of rhetoric and comparative literature at the University of California at Berkeley:

The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.1

Murky writing comes from murky thinking. It is also a defensive tactic, like a squid squirting ink when attacked.

The reasons for this are interesting…

Perspectivism and Postmodernism

Nietzsche is the grandfather of postmodernism. His core idea, perspectivism, is central to it: there is no truth, only various interpretations from the varying perspectives of power-hungry individuals, interpretations that serve to enhance the power of these individuals.

If you understand this, you’ll understand the Marxist roots of critical theory, as Thomas Nagel lucidly explains:

The explanation of all ostensibly rational forms of thought in terms of social influences is a generalization of the old Marxist idea of ideology, by which moral principles were all debunked as rationalizations of class interest. The new relativists, with Nietzschean extravagance, have merely extended their exposure of the hollowness of pretensions to objectivity to science and everything else. Like its narrower predecessor, this form of analysis sees "objectivity" as a mask of the exercise of power, and so provides natural expression of class hatred. Postmodernism's specifically academic appeal comes from its being another in the sequence of all-purpose "unmasking" strategies that offer a way to criticize the intellectual efforts of others, not by engaging with them on the ground, but by diagnosing them from a superior vantage point and charging them with inadequate self-awareness. Logical positivism and Marxism have in the past been used by academics in this way, and postmodernist relativism is natural for the role. It may now be on the way out, but I suspect there will continue to be a market in the huge American academy for a quick fix of some kind. If it is not social constructionism, it will be something else -- Darwinian explanations of virtually everything, perhaps.2

So postmodernists, following Nietzsche, say the world is a vast constellation of ever-changing power-centres vying with each other for dominance, and what a particular power-centre calls 'true' are merely those interpretations that enhance and preserve its power.

But is perspectivism true? If so, there is an absolute truth after all. Nietzsche never extricated himself from this contradiction. If it is true, then it is false. If it is false, then it is false. So it is necessarily false. Postmodernism is necessarily false.

But what if somebody says he doesn’t care if postmodernism is necessarily false? What if he's going to embrace falsehood knowingly? (Again, this is pure Nietzsche: 'why truth?') What then?

According to St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics, Book XII, Lecture 9,

"We should love both: those whose opinion we follow, and those whose opinion we reject. For both have applied themselves to the quest for the truth, and both have helped us in it."

But those who no longer apply themselves to the quest for truth, however, cannot help us. They are corrupt. And corrupt minds, as Elizabeth Anscombe noted, cannot be reasoned with.

Bullshit

You must learn to sniff out bullshit. For a statement to count as a lie, two conditions must be satisfied: (a) the statement must be false; (b) the statement must be made with the intention to deceive. These conditions are individually necessary and jointly sufficient.

By contrast, a statement that is bullshit is, according to Harry Frankfurt,

‘grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true. It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth — this indifference to how things really are — that I regard as of the essence of bullshit.’3

Postmodernism, as we have seen, is necessarily false. Postmodernists, then, are either just plain wrong (because their statements are false), liars (if they make those false statements with the intention to deceive), or bullshitters (if they are indifferent to how things really are).

There is no alternative.

Recovering Roots

Recall that E. R. Curtius, the great literary scholar writing to affirm the unity of European civilisation in response to the Nazi totalitarian threat, defined literature as ‘the great intellectual and spiritual tradition of Western culture as given form in language’.

In A Defence of the Realm, David Conway describes the 'systematic deracination of the citizens of western liberal democracies since World War two':

Through changes in educational curricula, plus other cultural changes, most notably in public broadcasting, the cultural majorities in these societies have been made increasingly unfamiliar with their national histories and traditions. Without adequate historical knowledge of their national histories and without encouragement and opportunity to participate in national traditions, the members of a society cannot be expected to have much understanding of or affection for them.4

To deracinate is to uproot. Solzshenitsyn put Conway's point chillingly: 'to destroy a people, you must first sever their roots'.

That is why English has been the epicentre of the woke attack on Western civilisation in the form of ‘critical theory’. If your aim is to destroy the West, then you can’t let people appreciate its greatest achievements. They might like it.

Literature is dangerous. It is the most intellectual of the arts: its medium, words, is the medium of thought itself. And it becomes classic by passing the test of time as a result of capturing enduring truths about human nature.

Western literature starts, for example, with an account of men fighting over a woman. Listen to Achilles: ‘Why must we battle Trojans, men of Argos? Why, why in the world if not for Helen with her loose and lustrous hair?’ And Odysseus endures all perils and resists all temptations – even immortality – to get back home to his wife. These timeless truths about men and women will bury their postmodern purported undertakers.

But literature is even more dangerous for another reason.

Christianity and the Classics

Most great English writers were Roman Catholic or Anglican: Chaucer, Shakespeare, Pope, Dryden, Swift, Dr. Johnson, Austen, Hopkins, and T. S. Eliot. Seamus Heaney and Geoffrey Hill are notable among modern writers. Milton was a Protestant. Even those who weren’t Christian (e.g., Joyce) started so far inside Christianity that no matter how far they walked away from it, they still wrote within it.

And the novel was a development unique to the Christian west. Oriental intellectuals, after contact with the West, judged the novel unlike anything in their own traditions.

What explains this? A few facts are suggestive:

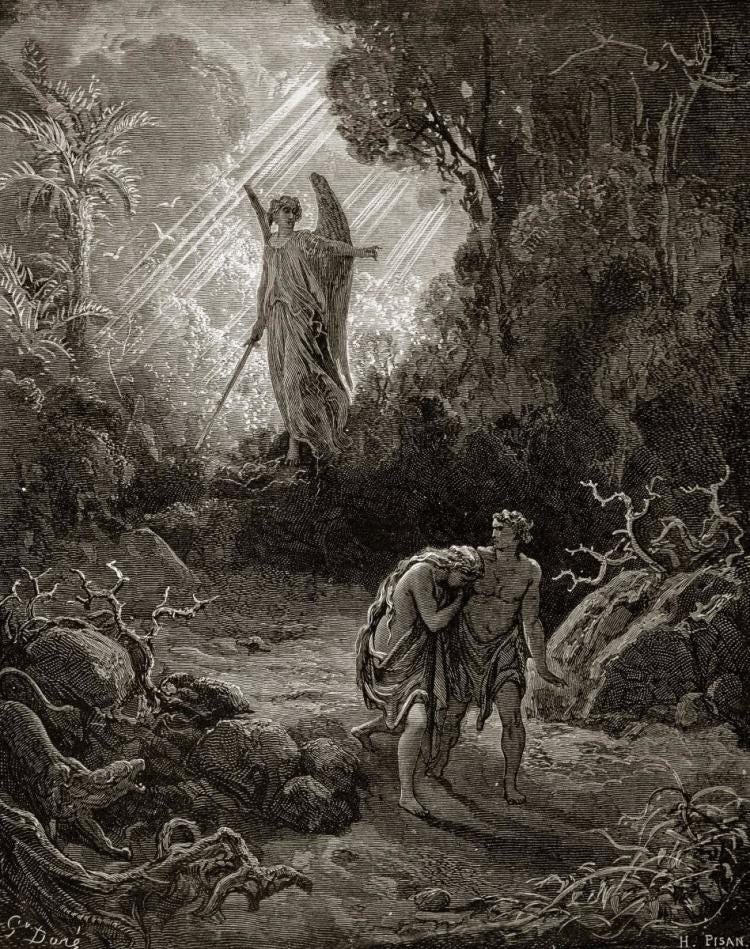

Christianity holds that reality is a grand story: Creation → Fall → Redemption.

The Bible is the biblioteca divina (L. 'divine library').

Christianity holds that the world is rational and real; unlike in Eastern religions, it is not an illusory chaos.

The Biblical style is characterised by metaphor and minimalism, encouraging artistic interpretation. Following A.N. Whitehead, who said that all philosophy is a footnote to Plato, we could say that English literature is a footnote to the Bible.

Christianity holds that man is rational and free. The novelist Walker Percy said that 'what distinguishes Christianity is its emphasis on the individual person, its view of man as a creature in trouble, seeking to get out of it, and accordingly on the move.'

Coda: The Common Bond

Remember Montaigne’s point that about ‘the bonds of our polity’? In his treatise on old age and again in the Pro Archia, Cicero made the argument that learning gives us a common bond (omnes arts quae ad humanities pertinent habent quoddam commune vinclum et quasi cognatione quadam inter se continentur).

No man by himself is able to attain the truth adequately (Aristotle's insight), although collectively men do not fail to amass a considerable amount, so learning – despite involving much individual discipline, effort and activity – is a collective endeavour.

And the central principle of Western civilisation, intellectual and philosophical realism – the belief that there exists a reality independent of our human wishes for it and of our human ideas of it, natural knowledge of which, through a discipline of the will and mind, is possible and indeed indispensable for human dignity – binds us because truth, the goal of learning, is the conformity of the mind with reality.

In conforming our minds to reality, we all come to know the same truth, which nobody owns, which is for everyone, and which makes us free because it is itself free. The modern denial of truth, which does leave only power, is the denial of this deepest spiritual bond between human beings. Du Bois put this movingly in his essay ‘Of the Training of Black Men’ (1902):

I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of Evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what souls I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil.

If any of this sounds even slightly quaint, it marks how much we have lost since even Conrad, one of the most experimental of modern novelists, could write that '[fiction is] a single-minded attempt to render the highest kind of justice to the visible universe, by bringing to light the truth’.

As the great Shakespeare scholar John Danby wrote as recently as 1948, at the opening of his study of King Lear as a work of moral and political philosophy, Shakespeare’s Doctrine of Nature,

we go to great writers for the truth. Or for whatever reason we do go to them in the first place it is for the truth we return to them, again and again.

In their pursuit of truth, their openness to the best in foreign intellectual traditions, and their willingness to subject to criticism the foundations of their own tradition, our great writers, particularly Shakespeare, embody the enduring, redemptive values of Western civilisation.

You owe a debt of gratitude to that civilisation, its laws, those who have worked to maintain and defend it, and especially those who have died in its defence. Its rise or fall can be nothing other than the sum total of the rise or fall of individual minds, so study as if your life depends on it.

It does.

“Further Reflections on the Conversations of Our Time,” an article in the scholarly journal Diacritics (1997)

"The Sleep of Reason" in Concealment and Exposure (Oxford 2002), p.174

Harry Frankfurt, On Bullshit (Princeton University Press, 2005, p.34).

In Defence of the Realm: The Worth of Nations in Classical Liberalism (Ashgate, 2004), p.192.

Thank you - and for every brave stance you and your family have taken.

My favourite article so far