On Christmas Day in 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne the Roman Emperor, making him protector of the Roman Church. Pope Adrian had just died, and his family didn’t like his replacement: Charlemagne’s knights, on their way to send their regards to Leo, stopped him having his eyes and tongue cut out in the street.

In Civilisation, Kenneth Clarke called Charlemagne ‘the first great man of action to emerge from the darkness since the collapse of the Roman world’. Even Alexander the Great, whose empire paved the way for the Roman Empire, doesn’t have an epic poem about him, but Charlemagne does: The Song of Roland.

In the sad fashion characteristic of academic ankle-biters, Professors Gaunt and Pratt note that, ‘troublingly, the lyricism of the poem’s celebration of military masculinity and its uncompromising patriotism are at times intensely moving.’

Before exploring the military masculinity of the poem, however, who was this great man of action? A huge man for his time, over six feet tall, Charlemagne had piercing blue eyes and fathered over eighteen children. And ‘without Charlemagne's tireless campaigning,’ Clarke reminds us, we should never have had the notion of a united Europe.’ This was done through the power of his sword.

Most notably, after eighteen campaigns in thirty years of constant fighting, he finally forced submission from the fearsome Saxons, who were known for roasting their prisoners in armour. He was ‘more or less actuated by the desire to extinguish what he and his people regarded as a form of devil-worship’. When he vanquished them, he chopped down the Irminsul, the pagan holy site supposed to be the base of the World Tree.

But he also stormed the Avar Ring, the capital of a tribe of fearsome horse warriors directly descended from Attila the Hun. And he crossed the Alps with a full army in mid-winter, matching a feat previously accomplished by Hannibal. But he never wore anything but a plain blue Frankish coat, although he did always wear a sword with it, even in his seventies.

It is probably true to say that Charlemagne saved Western civilisation, and Europe emerged from the break-up of his empire. The Song of Roland, probably the earliest (c. 1100) chanson de geste (‘song of heroic deeds’) and the masterpiece of the genre, takes as it subject the historical Battle of Roncesvalles (Roncevaux) in 778.

This was actually a skirmish between Charlemagne’s army and Basque forces, but the poem, written a few centuries afterwards, transforms it into a symbolic battle against Saracens. It has the heroic dimensions of the Greek defence of Thermopylae against the Persians in the 5th century BC. ‘When it is known no prisoners will be made,’ the poet laconically reminds us, ‘men fight back fiercely’.

What follows is an introduction to the poem aimed at gaining it new readers. As far as possible, I will let the poem speak for itself, drawing attention to its shape and substance by selecting important passages. But I will elucidate its themes to facilitate understanding and enjoyment - the ultimate aim, as T. S. Eliot said, of all scholarship (and often forgotten today).

When the poem begins, Charlemagne has conquered all of Spain except Saragossa:

The Emperor Charles is glad and full of cheer. Cordova’s taken, the outer walls are pierced, His catapults have cast the towers down sheer; Rich booty’s gone to all his chevaliers, Silver and gold and goodly battle-gear. In all the city no paynim now appears Who is not slain or turned to Christian fear.

The Saracen king then sends overtures:

He tells his men: “My barons, go with speed;

Bear in your hands boughs of the olive tree.

On my behalf King Charlemayn beseech,

For his God’s sake to show me clemency.

Say, this month’s end in truth he shall not see

Ere I shall seek him with thousand vassals leal.

The law of Christ I’ll then and there receive,

In faith and love I will his liegeman be.

I’ll send him sureties if thus he shall decree.”

The messengers have no difficulty recognising Charlemagne, the image of the ideal king:

White are his locks, and silver is his beard, His body noble, his countenance severe: If any seek him, no need to say, “Lo, here!”

He welcomes them with generous hospitality, showing his noble spirit, and they offer him great riches and promise king Marsilion’s conversion:

Much hath he studied the saving faith and true.

Now of his wealth he would send you in sooth

Lions and bears, leashed greyhounds not a few,

Sev’n hundred camels, a thousand falcons mewed,

And gold and silver borne on four hundred mules;

A wagon-train of fifty carts to boot,

And store enough of golden bezants good

Wherewith to pay your soldiers as you should.

Too long you’ve stayed in this land to our rue:

To Aix in France return you at our suit.

Thither my liege will surely follow you,

And will become your man in faith and truth,

And at your hand hold all his realm in feu!”

Although many sons of Spain are promised as a further guarantee, Charlemagne is cautious:

Early from bed the Emperor now is got;

At mass and matins he makes his orison.

Beneath a pine straightway the King is gone,

And calls his barons to council thereupon;

By French advice whate’er he does is done.

He is a model leader: his great piety means he attends Mass before responding to the envoys, and his noblemen advise him. Roland, the headstrong young warrior, doesn’t trust the Saracens, remembering how before

wrought Marsile a very treacherous deed:

He sent his Paynims by number of fifteen,

All of them bearing boughs of the olive tree,

And with like words he sued to you for peace.

Then did you ask the French lords for their rede;

Foolish advice they gave to you indeed.

You sent the Paynim two counts of your meinie:

Basan was one, the other was Basile.

He smote their heads off in hills beneath Haltile.

This war you’ve started wage on, and make no cease;

To Saragossa lead your host in the field,

Spend all your life, if need be, in the siege,

Revenge the men this villain made to bleed!”

Charlemagne sits still, head bent, stroking his beard and moustaches gently.

And then Ganelon fiercely disagrees with Roland, his step-son:

The man who tells you this plea should be rejected

Cares nothing, Sire, to what death he condemns us.

Counsel of pride must not grow swollen-headed;

Let’s hear wise men, turn deaf ears to the reckless.

So Roland nominates his stepfather to negotiate peace terms, infuriating him:

His great furred gown of marten he flings back

And stands before them in his silk bliaut clad.

Bright are his eyes, haughty his countenance,

Handsome his body, and broad his bosom’s span;

The peers all gaze, his bearing is so grand.

He says to Roland: “Fool! what has made thee mad?

I am thy step-sire, and all these know I am,

And me thou namest to seek Marsilion’s camp!

If God but grant I ever thence come back

I’ll wreak on thee such ruin and such wrack

That thy life long my vengeance shall not slack.”

Roland laughs in his face, at which Ganelon ‘very nearly goes out of his mind’. This lack of composure is a telling flaw in his masculinity. But Charlemagne orders him to go, and he must do his duty.

Angry because Roland proposed him for the dangerous task, Ganelon plots with the Saracens to achieve his stepson’s destruction: ‘each to other begins to speak with guile.’ In contrast to the calm Charlemagne, the hotheaded king, enraged, at first moves to kill the messenger, and his men have to restrain him. Marvelling at Charlemange, who inspires awe even in his enemies, he then asks, will he ever tire of fighting?

‘That’s not his way,’ Ganelon replies:

Howe’er I sounded his praise and his esteem,

His worth and honour would still outrun my theme.

His mighty valour who could proclaim in speech?

God kindled in him a courage so supreme,

He’d rather die than fail his knights at need.”

Ganelon warns of the formidable Roland, his step-son:

…while Roland still bears sword;

There’s none so valiant beneath the heavens broad,

…while Roland sees the light;

Twixt east and west his valour has no like

‘What must I do to bring Roland to die?’ asks the Saracen king. ‘I’ll tell you that’, replies Ganelon: he will ensure Roland commands the rear guard of the army when it withdraws from Spain. Although the Saracen losses will be heavy, Ganelon warns, they will be able to outnumber and defeat Roland and Oliver. And then Ganelon gives Marsile his oath.

One of the most infamous of literary traitors, he is included in Dante’s Hell.

Marsilion’s hand on Guènes’ shoulder lies;

He says to him: “You are both bold and wise.

Now by that faith which seems good in your eyes

Let not your heart turn back from our design.

Treasure I’ll give you, a great and goodly pile,

Ten mule-loads gold, digged from Arabian mines;

No year shall pass but you shall have the like.

Take now the keys of this great burg of mine,

Offer King Charles all its riches outright.

Make sure that Roland but in the rear-guard rides,

And if in pass or passage I him find

I’ll give him battle right bitter to abide.”

“I think”, said Guènes, “that I am wasting time.”

He mounts his horse and on his journey hies.

What should it profit a man if he gain the whole world but lose his own soul? As Dorothy Sayers noted, ‘so the grand outline of the poem defines itself: a private war is set within a national war, and the national war again within the world-war of Cross and Crescent. The small struggle at the centre shakes the whole web. The evil that is done can never be undone.’

The description of Ganelon’s return again highlights Charlemagne’s nobility and piety, as well as the bravery and bond of Roland and Oliver. Ganelon, by contrast, is a hollow, slinking half-man:

Early that day the Emperor leaves his bed.

Matins and mass the King has now heard said;

On the green grass he stood before his tent.

Roland was with him, brave Oliver as well,

Naimon the Duke and many another yet.

Then perjured Guènes the traitor comes to them

And starts to speak with cunning false pretence.

Few works of literature are as directly concerned with the meaning of masculinity and its relationship to conflict. When, towards the end of the poem, Charlemagne receive a blow that almost fells him, he hears the voice of St Gabriel rallying him, but it offers only challenge, not comfort: “And what,” said he, “art thou about, great King?” The hero is called forth.

Read rightly, the poem asks each of us what we are about. Its sinewy lyricism is sober, sparse and stark. One of the few moments of poignant emotion is when they pass the gates. Charlemagne had ominous dreams the night before:

The day goes down, dark follows on the day.

The Emperor sleeps, the mighty Charlemayn.

He dreamed he stood in Sizer’s lofty gate,

Holding in hand his ashen lance full great.

Count Ganelon takes hold of it, and shakes,

And with such fury he wrenches it and breaks

That high as heaven the flinders fly away.

Carlon sleeps on, he sleeps and does not wake.

This dream disturbs him, lingering in his mind long afterwards. And another follows:

That in his chapel at Aix in France was he;

In his right arm a fierce bear set its teeth.

Forth from Ardennes he saw a leopard speed,

That with rash rage his very body seized.

Then from the hall ran in a greyhound fleet,

And came to Carlon by gallops and by leaps.

From the first brute it bit the right ear clean,

And to the leopard gives battle with great heat.

The French all say the fight is good to see,

But none can guess which shall the victor be.

Carlon sleeps on; he wakes not from his sleep.

The bear is Ganelon; the leopard, Marsilion; the greyhound, Roland.

Charlemagne, concerned, asks who shall have the rearguard to hold the pass:

Quoth Ganelon: “I name my nephew Roland;

You have no baron who can beat him for boldness.”

When the King heard, a stern semblance he showed him:

“A fiend incarnate you are indeed”, he told him;

“Malice hath ta’en possession of you wholly!

But Ganelon feigns fidelity, recommending that Roland’s place at Charlemagne’s own vanguard be taken by Ogier the Dane, since ‘no baron can do it with more prowess’.

When Charlemagne had ordered Ganelon to go to the Saracen king, Ganelon had dropped the ‘right-hand glove’ of the king into the dust, an ominous omen. Roland, on hearing that Ganelon has nominated him to hold the pass, remembers this shame:

When Roland hears that to the rearward guard

His stepsire names him, he speaks in wrath of heart:

“Ah! coward wretch, foul felon, baseborn carle,

Didst think the glove would fall from out my grasp…

“Just Emperor,” then besought Count Roland bold,

“From your right hand deliver me your bow;

No man, I swear, shall utter the reproach

That I allowed it to slip from out my hold…”

The Emperor sits with his head bended low,

On cheek and chin he plucks his beard for woe,

He cannot help but let the tears o’erflow.

It is done. Ganelon ‘has the false lord Ganelon betrayed / Vast the reward the paynim king has paid’. The journey through the pass is one of the most touching moments in the poem:

High are the hills, the valleys dark and deep,

Grisly the rocks, and wondrous grim the steeps.

The French pass through that day with pain and grief;

The bruit of them was heard full fifteen leagues.

But when at length their fathers’ land they see,

Their own lord’s land, the land of Gascony,

Then they remember their honours and their fiefs,

Sweethearts and wives whom they are fain to greet,

Not one there is for pity doth not weep.

Charles most of all a boding sorrow feels,

His nephew’s left the Spanish gates to keep;

For very ruth he cannot choose but weep.

The French have been in Spain for seven years: they long to see their lands and loved ones. But as the Pyrenees Mountains loom over them, a shadow also looms over Charlemagne’s heart: the angelic dream vision of the shattered lance. Charlemagne’s tears don’t detract from his masculinity. In Macbeth, when Malcolm - watching MacDuff weep after he learns Macbeth has, in his absence, butchered his wife and children - tells him to ‘dispute it like a man’, MacDuff replies, ‘I shall do so, but I must also feel it as a man’.

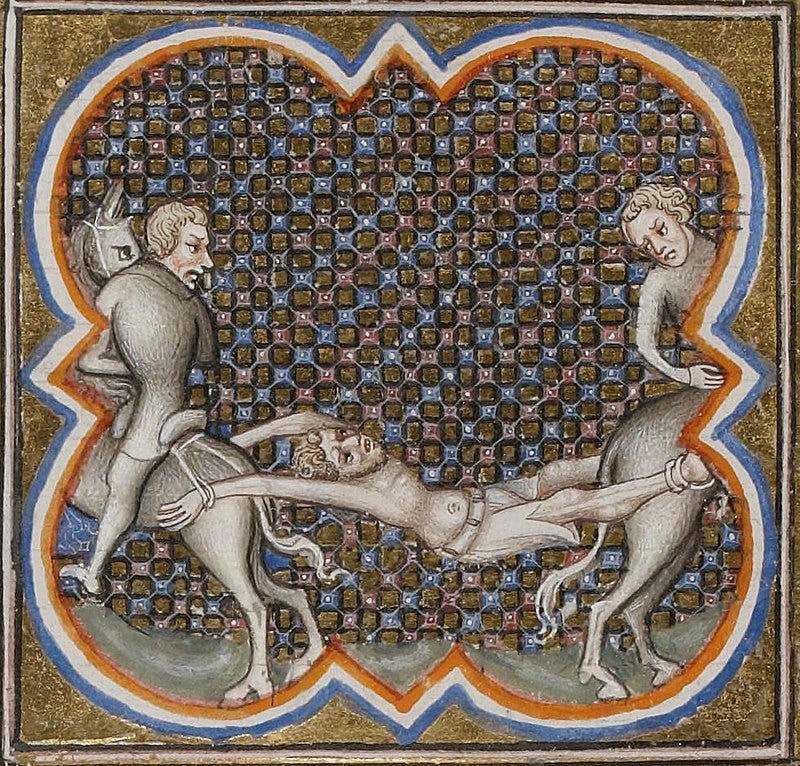

As the army crosses the Pyrenees, the rear guard is surrounded at the pass of Roncesvalles by an overwhelming Saracen force. The poet’s portraits of the Twelve Champions among them, all begging for Roland’s blood, are nevertheless respectful: there is a bond between men-at-arms, even foes. For example,

From Balaguet there cometh an Emir;

His form is noble, his eyes are bold and clear,

When on his horse he’s mounted in career

He bears him bravely armed in his battle-gear,

And for his courage he’s famous far and near;

Were he but Christian, right knightly he’d appear.

Or again:

Then comes at speed Margaris of Seville,

Who holds his land as far as Cazmarin.

Ladies all love him, so beautiful he is,

She that beholds him has a smile on her lips,

Will she or nill she, she laughs for very bliss,

And there’s no Paynim his match for chivalry.

But the keynote is disaster:

Last there comes Chernubles of Munigre;

His unshorn hair hangs trailing to his feet.

He for his sport can shoulder if he please

More weight than four stout sumpter-mules can heave.

He dwells in regions wherein, so ’tis believed,

Sun never shines nor springs one blade of wheat,

No rain can fall, no dew is ever seen,

There, every stone is black as black can be,

And some folk say it’s the abode of fiends.

The odds are crushing:

One hundred thousand stout Saracens they lead.

Each one afire with zeal to do great deeds.

Beneath a pine-grove they arm them for the field.

‘The 5-million-year-long-trail to our modern selves was lined, along its full stretch, by a male aggression that structured our ancestors’ social lives and technology and minds.’

- Richard Wrangham, Harvard Professor of Anthropology1

Yet Roland, headstrong, will not yield - the paragon of valour, victorious even in defeat.

Great is the noise; it reaches the French lines.

Quoth Oliver: “I think, companion mine,

We’ll need this day with Saracens to fight.”

Roland replies: “I hope to God you’re right!

Here must we stand to serve on the King’s side.

Men for their lords great hardship must abide,

Fierce heat and cold endure in every clime,

Lose for his sake, if need be, skin and hide.

Look to it now! Let each man stoutly smite!

No shameful songs be sung for our despite!

Paynims are wrong, Christians are in the right!

Ill tales of me shall no man tell, say I!”

‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’ But there is a clash between Roland, whose courage borders on recklessness, and his more prudent friend Oliver. ‘Roland is fierce and Oliver is wise.’ There are divergent conceptions of feudal loyalty.

The feudal world is alien to us now. Dorothy Sayers perceptively remarks that ‘the present century has contrived so to cheapen all human relationships that it is difficult to find an unambiguous word for this strong blend of affection, admiration, and loyalty between two men.’ But the perilous world of the poem necessitated military prowess. The protector role was primary. On the baron’s strength depended all.

Although effete critics might sneer at this, without the heroic virtues, now as then, no higher virtues are possible. And now as then, some of the deepest male bonds are between brothers-in-arms. Oliver warns the men about what he has seen, but they are undeterred:

Quoth Oliver: “The Paynim strength I’ve seen;

Never on earth has such a hosting been:

A hundred thousand in van ride under shield

Their helmets laced, their hauberks all agleam

Their spears upright, with heads of shining steel.

You’ll have such battle as ne’er was fought on field.

My lords of France, God give you strength at need!

Save you stand fast, this field we cannot keep.”

The French all say: “Foul shame it were to flee!

We’re yours till death; no man of us will yield.”

Oliver advises Roland to summon help from Charlemagne. They need reinforcements. But Roland’s judgement is clouded by his preoccupation with his personal renown. There is an air of Achilles about him.

Quoth Oliver: “Huge are the Paynim hordes,

And of our French the numbers seem but small.

Companion Roland, I pray you sound your horn,

That Charles may hear and fetch back all his force.”

Roland replies: “Madman were I and more,

And in fair France my fame would suffer scorn.

I’ll smite great strokes with Durendal my sword,

I’ll dye it red high as the hilt with gore.

This pass the Paynims reached on a luckless morn;

I swear to you death is their doom therefor.”

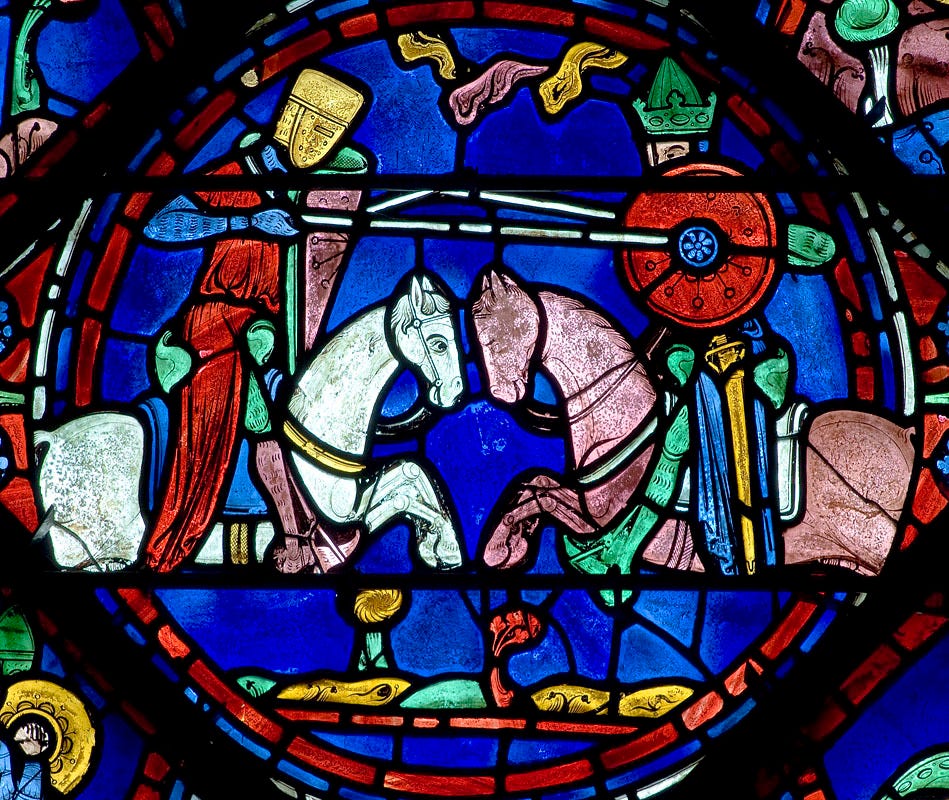

Thrice Oliver asks, and thrice Roland refuses: ‘blood-red the steel of Durendal shall flow.’ And so the hopeless battle is joined.

Roland is fierce and Oliver is wise

And both for valour may bear away the prize.

Once horsed and armed the quarrel to decide,

For dread of death the field they’ll never fly.

The counts are brave, their words are stern and high.

Now the false Paynims with wondrous fury ride.

Quoth Oliver: “Look, Roland, they’re in sight.

Charles is far off, and these are very nigh;

You would not sound your Olifant for pride;

Had we the Emperor we should have been all right.

To Gate of Spain turn now and lift your eyes,

See for yourself the rear-guard’s woeful plight.

Who fights this day will never more see fight.”

Roland replies: “Speak no such foul despite!

Curst be the breast whose heart knows cowardise!

Here in our place we’ll stand and here abide:

Buffets and blows be ours to take and strike!”

E. M. Forster famously contrasted round and flat characters. The former have depth and internal conflict. They are human. The latter, lacking such complexity, inhabit melodrama: you know what the pantomime villain is going to do next. Roland and Oliver, despite their greatness, are both round, flawed, human.

They aren’t idealised. Is Roland too proud? Why didn’t Oliver blow the horn himself? Wisdom and ferocity combined might have carried the day. But the Archbishop Turpin reminds them they will at least die as martyrs:

“Barons, my lords, Charles picked us for this purpose;

We must be ready to die in our King’s service.

Christendom needs you, so help us to preserve it.

Battle you’ll have, of that you may be certain,

Here come the Paynims—your own eyes have observed them.

Now beat your breasts and ask God for His mercy:

I will absolve you and set your souls in surety.

If you should die, blest martyrdom’s your guerdon;

You’ll sit on high in Paradise eternal.”

This exhortation to engage in battle with penitent hearts and sincere loyalty evokes the attitudes to religious war and martyrdom that prevailed during the First Crusade, shortly before the earliest surviving manuscripts of the poem. There, too, many great men gave all.

A Saracen mocks Roland:

Now Adelroth, (he was King Marsile’s nephew),

Before the host comes first of all his fellows;

With evil words the French he thus addresses:

“Villainous Franks, with us you have to reckon!

You’ve been betrayed by him that should protect you,

Your king lacked wit who in the passes left you.

Fair France will lose her honour in this venture;

From Carlon’s body the right arm will be severed.”

This defiance was a standard part of the proceedings of combat. In response, Roland’s ‘rage is reckless’:

He spurs his horse, gives full rein to his mettle,

His blow he launches with all his mightiest effort;

The shield he shatters, and the hauberk he rendeth,

He splits the breast and batters in the breast-bone,

Through the man’s back drives out the backbone bended,

And soul and all forth on the spear-point fetches;

Clean through he thrusts him, forth of the saddle wrenching,

And flings him dead a lance-length from his destrier;

Into two pieces he has broken his neckbone.

His boast, the standard conclusion to the proceedings, follows:

No less for that he speaks to him and tells him:

“Out on thee, churl! no lack-wit is the Emperor,

He is none such, nor loved he treason ever;

Right well he did who in the passes left us,

Neither shall France lose honour by this venture.

First blood to us! Go to it, gallant Frenchmen!

Right’s on our side, and wrong is with these wretches!”

Although this sits uneasily with English notions of sportsmanship, it is standard for early epic. In Homer, these speeches are often very lengthy, but in Roland they are laconic and cutting.

As customary, Roland fights with his spear until it shatters, and then he uses his sword:

Great is the battle and crowded the mellay,

Nor does Count Roland stint of his strokes this day;

While the shaft holds he wields his spear amain—

Fifteen great blows ere it splinters and breaks.

Then his bare brand, his Durendal, he takes..

Against Chernubles, the Saracen from the land where the ‘sun never shines’, Roland then rides. Both hands were often used for swords, the aim being to bring the edge, not the point, of the blade down on the opponent’s head, so Roland

Splits through the helm with carbuncles ablaze,

Through the steel coif, and through scalp and through brain

’Twixt the two eyes he cleaves him through the face;

Through the bright byrny close-set with rings of mail,

Right through the body, through the fork and the reins,

Down through the saddle with its beaten gold plates,

Through to the horse he drives the cleaving blade,

Seeking no joint through the chine carves his way,

Flings horse and man dead on the grassy plain.

“Foul befal, felon, that e’er you sought this fray!

Mahound”, quoth he, “shall never bring you aid.

Villains like you seek victory in vain.”

But so fierce is the fighting that Roland’s horse becomes ‘bloody from crest to withers’, and there are ‘many French in flower of youth laid low, / Whom wives and mothers shall never more behold’.

Nor Charles, who scans the pass with anxious eyes.

Throughout all France terrific tempests rise,

Thunder is heard, the stormy winds blow high,

Unmeasured rain and hail fall from the sky,

While thick and fast flashes the levin bright,

And true it is the earth quakes far and wide.

As King Marsile himself rides up with reinforcements, Roland turns to Oliver:

“Brother,” quoth Roland, “friend Oliver, sweet lord,

It is our death false Ganelon has sworn;

The treason’s plain, it can be hid no more;

A right great vengeance the Emperor will let fall.

But we must bide a fearful pass of war.

No man has ever beheld the like before.

I shall lay on with Durendal my sword,

You, comrade, wield that great Hauteclaire of yours.

In lands how many have we those weapons borne!

Battles how many victoriously fought!

Ne’er shall base ballad be sung of them in hall!”

They desire to fight well to honour not only themselves and the Emperor but their weapons, too. Through the poem runs a profound connection between men and metal. It is another of the many bonds forged in battle. In the Iliad, for example, the war horses weep for their fallen riders.

Then comes a duel between the Saracen Abisme - ‘in all that host was none more vile than he’ - and the good Archbishop, who ‘observes him, much displeased’.

From flank to flank he spits his body through,

And flings him dead wherever he finds room.

The French all cry: “A valiant blow and shrewd!

Right strong to save is our Archbishop’s crook!”

Roland, impressed, calls out to Oliver:

Fair sir, companion, confess that for this gear

Our lord Archbishop quits him like any peer;

Earth cannot match him beneath the heavens’ sphere,

Like Christ, the Archbishop came to bring not peace but a sword. Turning the other cheek is a private, not public, injunction.

Although some Saracens begin to flee from the fierce fighting, when Roland ‘sees all his brave men down’, he laments, ‘well may we pity this fair sweet France of ours, / Thus left so barren of all her knighthood’s flower.’ And so he agrees to blow the horn.

But Oliver is angry at Roland:

“Companion, you got us in this mess.

There is wise valour, and there is recklessness:

Prudence is worth more than foolhardiness.

Through your o’erweening you have destroyed the French;

Ne’er shall we do service to Charles again.

Had you but given some heed to what I said,

My lord had come, the battle had gone well,

And King Marsile had been captured or dead.

Your prowess, Roland, is a curse on our heads.

No more from us will Charlemayn have help,

Whose like till Doomsday shall not be seen of men.

Now you will die, and fair France will be shent;

Our loyal friendship is here brought to an end;

A bitter parting we’ll have ere this sun set.”

But the Archbishop, hearing their dispute, rebukes them:

Let’s have no quarrel, o’God’s name, ’twixt you two.

It will not save us to sound the horn, that’s true;

Nevertheless, ’twere better so to do.

Let the King come; his vengeance will be rude…

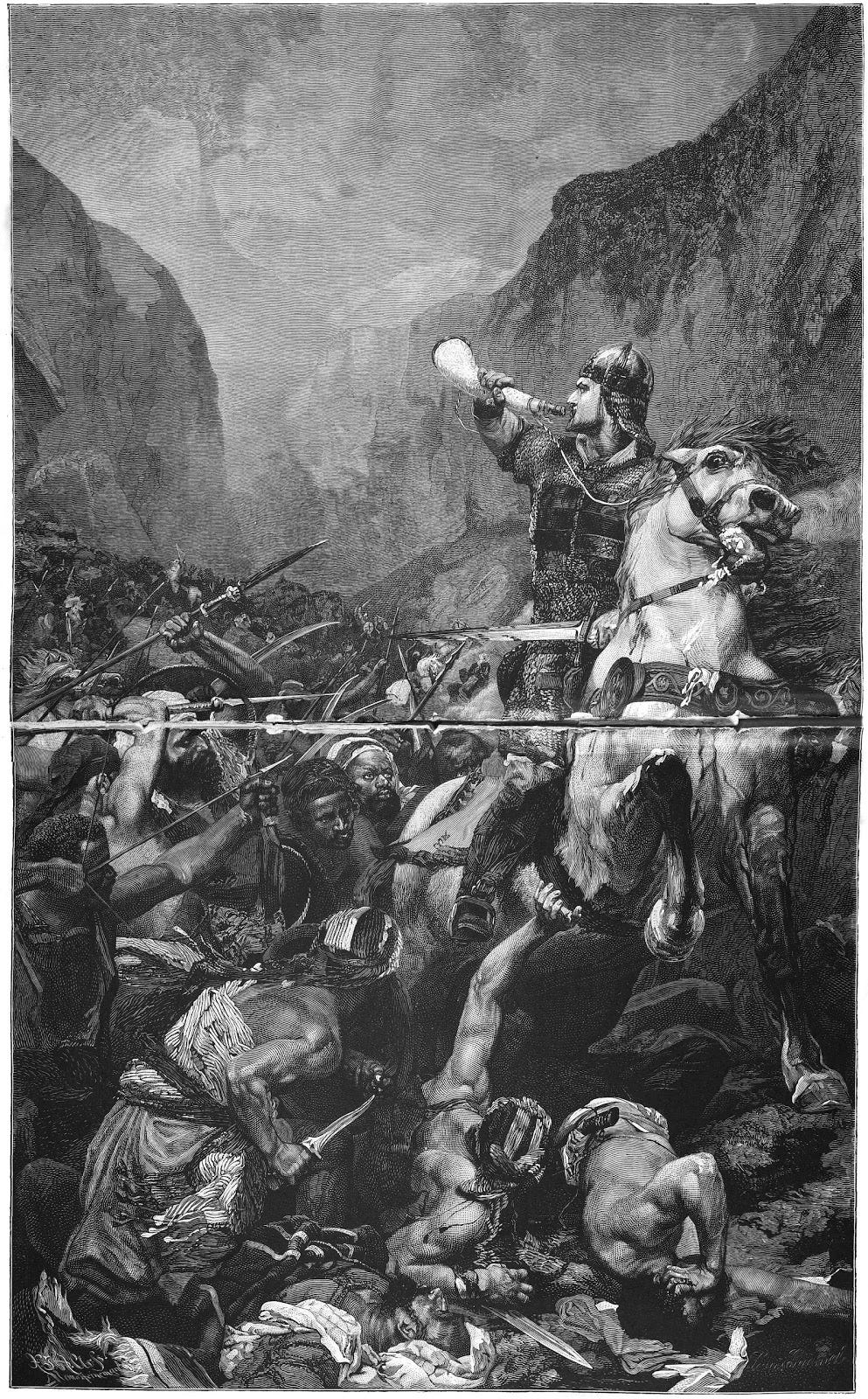

Roland finally blows the horn to summon Charlemagne, mortally wounding himself by bursting his temples:

The County Roland with pain and anguish winds

His Olifant, and blows with all his might.

Blood from his mouth comes spurting scarlet-bright

He’s burst the veins of his temples outright.

Charlemagne hears it, so ‘long of breath’, blown ‘with all a brave man’s strength’. Ganelon is then chained ‘like a bear in a cage’ (recalling the dream vision of the bear), and ‘in wrath of heart the Emperor Carlon rides’. The odds are against him: ‘huge are the hills and shadowy and high’.

Roland knows they won’t make it in time. And yet he will die like a man:

Fail not, for shame, right dear to sell your lives.

Lift up, my lords, your burnished blades and fight!

Come life, come death, the foe shall pay the price,

Lest we should bring fair France into despite!

When on this field Carlon my lord sets eyes

He’ll see what toll we’ve taken of their might.

Courageous action, said Aristotle, requires either hope of safety, or hope of success, or both. Thus he judged that the Spartans at Thermopole could display courage even though they knew that they were doomed. Why? There was still hope of achieving the worthwhile goal of slowing down the enemy.

So, too, Roland. Seeing the dwindling French numbers, the Saracens plume themselves, puffed up with pride and hope:

“Now to the Emperor,” they say, “his crimes come home!”

Marganice comes, riding a sorrel colt;

He spurs him hard with rowels all of gold,

And from behind deals Oliver a blow;

Deep in his back the burnished mail is broke,

That the spear’s point stands forth at his breast-bone.

He saith to him: “You’ve suffered a sore stroke;

Charlemayn sent you to the pass for your woe.

Foul wrong he did us, ’tis good he lose his boast:

I’ve well requited our loss on you alone.”

To strike an opponent from behind was against the rules of engagement. There is no honour here.

Oliver feels that he is hurt to death;

He grasps his sword Hauteclaire the keen of edge,

Smites Marganice on his high golden helm,

Shearing away the flowers and crystal gems,

Down to the teeth clean splits him through the head,

Shakes loose the blade and flings him down and dead;

Then saith: “Foul fall you, accursèd Paynim wretch!

Charles has had losses, so much I will confess:

But ne’er shall you, back to the land you left,

To dame or damsel return to boast yourself

That e’er you spoiled me to the tune of two pence,

Or made your profit of me or other men.”

He then cries to Roland for help:

Oliver’s face, when Roland on him looks,

Is grey and ghastly, discoloured, wan with wounds,

His bright blood sprays his body head to foot;

Down to the ground it runs from him in pools.

“God!” says the Count, “I know not what to do!

Fair sir, companion, woe worth your mighty mood!—

Ne’er shall be seen a man to equal you.

Alas, fair France! what valiant men and true

Must thou bewail this day, cast down and doomed!

Bitter the loss the Emperor has to rue!”

So much he says, and in the saddle swoons.

The poem is clear on not just the physical but the emotional wounds of war. Oliver has bled so much that he can see ‘nothing straight / Nor recognise a single living shape’, so he strikes Roland:

Then Roland, stricken, lifts his eyes to his face,

Asking him low and mildly as he may:

“Sir, my companion, did you mean it that way?

Look, I am Roland, that loved you all my days;

You never sent me challenge or battle-gage.”

Recognising Roland’s voice, Oliver prays to be pardoned. Now not only blind but totally deaf, he feels death approach:

His heart-strings crack, he stoops his knightly helm,

And sinks to earth, and lies there all his length.

Dead is the Count, his days have reached their end.

The valiant Roland weeps for him and laments,

No man on earth felt ever such distress.

Only Roland, Walter de Hum and the Archbishop remain standing:

Betwixt their valours there’s not a pin to choose.

In the thick press they smite the Moorish crew.

A thousand Paynims dismount to fight on foot,

And forty thousand horsemen they have, to boot,

Yet ’gainst these three, my troth! they fear to move.

‘With what sort of terrible things, then, is the brave man concerned? Surely with the greatest; for no one is more likely than he to stand his ground against what is dreadful. Now death is the most terrible of all things.’

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1115a24-26

But move they do, and only Roland remains. He sees the Archbishop’s ‘bowels gush forth out of his side / And on his brow the brain laid bare to sight’. Roland himself soon ‘lies senseless on the greensward’:

a Saracen is there, watching him keenly;

He has feigned death, and lies among his people,

And has smeared blood upon his breast and features.

Now he gets up and runs towards him fleetly;

Strong was he, comely and of valour exceeding.

Now in his rage and in his overweening

He falls on Roland, his arms and body seizing;

He saith one word: “Now Carlon’s nephew’s beaten.

I’ll take his sword, to Araby I’ll reive it.”

But as he draws it Roland comes to, and feels him.

Roland has felt his good sword being stol’n;

Opens his eyes and speaks this word alone:

“Thou’rt none of ours, in so far as I know.”

He takes his horn, of which he kept fast hold,

And smites the helm, which was all gemmed with gold;

He breaks the steel and the scalp and the bone,

And from his head batters his eyes out both,

And dead on ground he lays the villain low;

Then saith: “False Paynim, and how wast thou so bold,

Foully or fairly, to seize upon me so?

A fool he’ll think thee who hears this story told.

Lo, now! the mouth of my Olifant’s broke;

Fallen is all the crystal and the gold.”

Roland then tries to smash his sword, too:

I cannot tell you how he hewed it and smote;

Yet the blade breaks not nor splinters, though it groans;

Upward to heaven it rebounds from the blow.

When the Count sees it never will be broke,

Then to himself right softly he makes moan:

“Ah, Durendal, fair, hallowed, and devote,

What store of relics lie in thy hilt of gold!

St Peter’s tooth, St Basil’s blood, it holds,

Hair of my lord St Denis, there enclosed,

Likewise a piece of Blessed Mary’s robe;

To Paynim hands ’twere sin to let you go;

You should be served by Christian men alone…

But Durendal has sliced the right arm of the Saracen king Marsile, frighting the whole Saracen army, and decapitated the king's son, Jursaleu. It will not shatter. The northmen, according to the French historian Lucien Musset noted, ‘were able to produce a special steel for the cutting edge of their swords or battle-axes which was unequalled until the nineteenth century’.2

But this sword goes deeper. It symbolises Roland’s loyalty to his lord: ‘My Durendal the Emperor gave to me’. And it is ‘hallowed’, holding many relics. So Roland hides it under his body as he dies. Finally arriving, Charlemagne sees Roland and faints:

Carlon the King out of his swoon revives.

Four barons hold him between their hands upright.

He looks to earth and sees his nephew lie.

Fair is his body, but all his hue is white.

His upturned eyes are shadowy with night.

By faith and love Charles mourns him on this wise:

“Roland, my friend, God have thy soul on high

With the bright Hallows in flowers of Paradise!

Thy wretched lord sent thee to Spain to die!

Never shall day bring comfort to my eyes.

How fast must dwindle my joy now and my might!

None shall I have to keep my honour bright!

Methinks I’ve not one friend left under sky;

Kinsmen I have, but none that is thy like.”

As he tears at his hair, all the French warriors cry with him. Although he feels it as a man, reproaching himself for having failed to protect Roland (‘thy wretched lord sent thee’), Charlemagne will also dispute it as man.

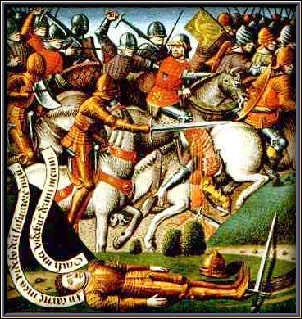

In the great final battle, Charlemagne and the Emir Baligant, lord of all Islam (who had promised his warrior not only booty but ‘fair women’), fight man to man.

They know each other by these clear calls and loud,

Each in mid-field has sought his foe and found.

They meet, they charge, exchanging mighty clouts,

On the ringed shields crash home the spearheads stout…

Both fall from their horses, quickly leaping to their feet and drawing their swords: ‘Charles of fair France is a great man of might, / And the Emir knows naught of fear or flight.’ Again, the poet admires the prowess of the Saracens: Charlemagne is put to the test.

Then comes the angel’s question to the wounded Charlemagne: ‘“And what,” said he, “art thou about, great King?”

When Charles thus hears the blessed Angel say,

He fears not death, he’s free from all dismay,

His strength returns, he is himself again.

At the Emir he drives his good French blade,

He carves the helm with jewel-stones ablaze,

He splits the skull, he dashes out the brains,

Down to the beard he cleaves him through the face,

And, past all healing, he flings him down, clean slain.

With Marsilon and Baligant slain, Sargagossa is taken. Its inhabitants are given the choice between death or baptism. Queen Bramimonda, however, is peaceably converted: ‘sermon and story on her heart have prevailed,’ symbolising Charlemagne’s total victory over the pagans.

But the poet does not shirk from the grim realities even after victory. Upon returning to France, Charlemagne breaks the news to Aude, Roland’s betrothed and the sister of Oliver. She falls dead at his feet. The tremendous and realistic weight of loss pulls at the margins of this paen to masculinity.

Roland felt it looking at Oliver’s body; Charlemagne felt it looking at Roland’s. Tolkien’s ‘Lament for the Rohirrim’ doubtless alludes to it:

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the hand on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing?

They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow;

The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow.

Who shall gather the smoke of the dead wood burning,

Or behold the flowing years from the Sea returning?

As for Ganelon, he claims he took legitimate revenge, openly proclaimed, and that it wasn’t treason. Although the council of barons are at first persuaded by this, Thierry, argues that Roland was serving Charlemagne when he took revenge. It was therefore betrayal of the emperor.

Ganelon's friend Pinabel challenges Thierry to trial by combat and, despite being the weaker man, defeats him with God’s help after being wounded first:

When Thierry feels the blade bite through his flesh,

And sees the blood upon the grass run red,

Then he lets drive a blow at Pinabel.

Down to the nasal he cleaves the bright steel helm,

Shears through the brain and spills it from his head,

Wrenches the blade out and shakes him from it dead.

With that great stroke he wins and makes an end.

The Franks all cry: “God’s might is manifest!

Justice demands the rope for Guènes’s neck,

And for his kinsmen who set their lives in pledge!”

Ganelon is then tortured to death as a traitor, and thirty of his relatives are also hung upon ‘the tree of doom’.

Ganelon’s torment is fearful and extreme,

For all his sinews are racked from head to heel,

His every limb wrenched from the sockets clean;

His blood runs bright upon the grassy green.

Ganelon’s dead—so perish all his breed!

’Twere wrong that treason should live to boast the deed.

And yet. Although Ganelon had told Marsilion that Charlemagne would ‘weary of going to the wars’ if Roland were dead, Charlemagne is Christ’s vassal. And to the war between belief and unbelief there is no end: “Never to Paynims may I show love or peace.” Once more the hero is called forth:

The day departs and evening turns to night;

The King’s abed in vaulted chamber high;

St Gabriel comes, God’s courier, to his side:

“Up, Charles! assemble thy whole imperial might;

With force and arms unto Elbira ride;

Needs must thou succour King Vivien where he lies

At Imphe, his city, besieged by Paynim tribes;

There for thy help the Christians call and cry.”

Small heart had Carlon to journey and to fight;

“God!” says the King, “how weary is my life!”

He weeps, he plucks his flowing beard and white.Here ends the geste Turoldus would recite.

‘Troublingly,’ Professors Gaunt and Pratt noted, ‘the lyricism of the poem’s celebration of military masculinity and its uncompromising patriotism are at times intensely moving,’ but the falling cadence of the poem’s finale reminds us that in this world you will have troubles.

As written in the Book of Job, ‘the life of man is a warfare.’

What art thou about?

Demonic Males (Bloomsbury, 1996), p.172

Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Europe AD 400–600. (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1993), p.203

Who thinks long articles like this would be better as podcasts?

Thank you for this thought provoking article. I enjoyed reading it.

I greatly prefer the written form. I can read it at my leisure, breaking off here and there to savour a passage or to look up a word and perhaps to indulge in a diversion as the etymology leads me to other thoughts. The written form also allows references to sources and places for further reading. I find that podcasts not only allow none of these, they allow no time for reflection. In consequence, I take in much less and retain much less. Podcasts usually leave me with little more than an impression of what a subject might be about if I were to read about it.

At one time the programme In Our Time on Radio 4 offered an email service which supplied the text of the programme. These programmes last for about 45 minutes. I worked through these email every week for several months. I found that most contained two ideas, a single example contained three and one contained only one idea. The rest of the programme was taken up with entertaining padding. I concluded that broadcasts and podcasts are a poor medium for conveying ideas, particularly ideas which require thought and challenge.

For these reasons, I think the written form will remain the best form for discussion of ideas.