In 476, the barbarian Odoacer - with no claim to the title other than his sword - dismissed the last Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustus, marking the end of the Western Empire. How this happened reveals timeless truths about cultural decline: writing of the Roman colony of Antioch, for example, Gibbon noted ‘the serious and manly virtues were the subject of ridicule’.1 Childlessness and sexual degeneracy were also common.

Rome’s Origins

First, though, what was Rome? Rodney Stark makes the perceptive point that ‘in many ways Rome was the Athenian Empire writ large’.2 Athens and Rome both began as city-states; both were almost always at war; both enjoyed a high degree of freedom; both suppressed innovation; both ended up Christian. And both, ultimately, fell to enemies from the north.

According to the first written accounts of centuries of oral traditions, Rome, which began in the eighth century BC, was first ruled by a series of seven kings. It became a republic in about 500 BC then achieved military domination of Italy and, after expanding into Sicily, came into conflict with Carthage, who ruled Sicily, resulting in the three Punic Wars (264–146 BC).

Naval losses made Carthage sign a peace treaty with Rome. But then Carthage invaded Spain, taking its silver mines. Rome, seeing this as provocation - although Spain was not then part of its empire - declared war. In 218 BC, Hannibal Barca, with unbelievable audacity, then took thirty-six elephants over the mid-winter Alps straight into Italy. He won every battle against Rome in Italy, killing over fifty thousand at the battle of Cannae in 216 BC.

After sixteen years undefeated in Italy despite having to live off the land, Hannibal returned to Carthage to fend off a Roman naval assault. Lacking his veteran troops, he then lost the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. In 149 BC, Rome, seeing signs Carthage might flourish again, destroyed it utterly. No buildings were left standing. Everyone was either killed or enslaved. Greece, much of Gaul, Spain, much of Persia, Palestine, and Egypt then Britain fell next.

Tensions in the Empire

Rome was freer than the tyrannical Eastern empires but less free than the Greek democracies. The Senate comprised a small group of patricians owning land worth at least 100,000 dinarii (professional Roman soldiers were paid one dinari a day). The Senate itself selected new senators and also selected - each for a one-year term - the two consuls, in whom executive power was vested. In 367 BC, the Plebeian Council was formed for men ineligible for the Senate; it, too, could pass laws, and eventually the Senate permitted the election of Plebeians.

Rome’s military victories created tremendous wealth. Plutarch says Caesar took over a million slaves from Gaul. But cheap slaves meant displaced independent farmers, their land either bought or usurped, created a dependent population. They had to be pacified with ‘bread and circuses’, including free seats in the arenas. And Rome no longer benefited from the farmers’ sons as citizen-soldiers. We will return to this point about sons later.

Both eager to back tyrants for immediate benefits, the mob and the army ended the republic. When Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, the power vacuum was filled in 31 BC by Octavian as Caesar Augustus, the first emperor of Rome; Emperors then ruled Rome until the last, Romulus Augustus.

A Copycat Culture

The Roman upper classes mostly spoke Greek, not Latin, and wealthy Romans sent their sons to be educated in Greece. The Romans also adopted all the Greek gods. Because the Roman temples depended on donations, they competed for support. Consequently, the culture was highly religious: even the poor had their names inscribed in temples as donors.

Not only Roman art, literature and philosophy were essentially Greek but also their technology. To put it simply, they preferred slaves to machinery. The Romans invented concrete but nothing else important. Roman roads were designed solely for marching soldiers, but even the soldiers preferred to walk alongside them. They were too hard when dry and too slippery when wet.

Public entertainment was usually torture or slaughter of prisoners or slaves. Even most gladiators were slaves. There was a creativity to the cruelty: female gladiators, bare-chested, battled male dwarves, and Nero sometimes forced wives of senators to fight in the arena. Julius Caesar once paid for a show involving 640 gladiators; the Senate stopped him having more. There were 251 amphitheaters in the empire, in which around 2.5 million people died.

The Decisive Change to the Army

The Roman army consisted of citizen-soldiers in phalanxes at first. The sons of the wealthiest families formed the front line. But it was redesigned in 387 BC after the Gauls outmanoeuvred the Roman phalanxes and sacked Rome. Mobility was emphasised, and soldiers came only from an elite group of property-owning citizens. They were selected by lot and supplied their own equipment.

After the Roman defeat at Noreia on the Danube in 112 BC, Marius redesigned the army again, introducing the legion - six thousand soldiers divided into ten cohorts, each of which consisted of six centuries - and abolishing the citizenship requirement. The army became professional, meaning soldiers were loyal to their generals, not Rome: they could overthrow emperors.

Rome persecuted Christians from the start, but by 303, when Galerius began it in earnest, Christians were the majority. Constantine converted after he won the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and seized the throne in 312, and every Roman emperor afterwards was Christian, except Julian, who ruled for fewer than two years. Rome shaped the Christian bureaucracy that would outlive the empire after the barbarian Odoacer dismissed the last Emperor, Romulus Augustus, in 476.

No Sudden Fall

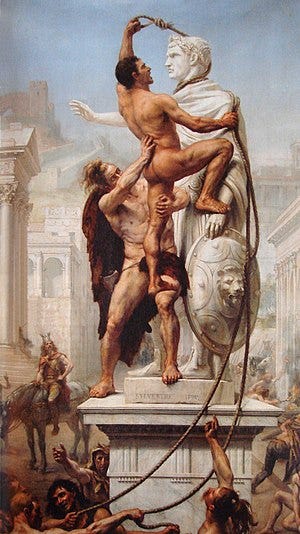

The Empire had been in its death throes since 410, when the Gothic army of King Alaric had sacked the city of Rome. ‘The whole world,’ lamented Saint Jerome, ‘perished in one city’. Several decades after the end of the Roman West, the Byzantine pagan Zosimus published a New History, arguing that abandoning the republic for rule by an emperor had led to increasingly unsupportable taxation, moral depravity, corruption, weakening of the army, and needless appeasement of the barbarians.

Above all, he said, “the precepts of Christian religion had the effect of debilitating the martial spirit.” Nearly all subsequent theories agree with Zosimus: Rome fell because of its internal failures and shortcomings, and the fall of Rome occurred primarily on the battlefield. No civilisation can maintain its privileges without training or fighting to defend them.

Rome did not - contrary to what some conservative commentators say - fall through miscegenation: genetics shows that Italians have retained their racial composition.

Recall that Gibbon, writing of the Roman colony of Antioch, noted ‘the serious and manly virtues were the subject of ridicule’. The Vandals numbered merely 15,000 fighting men, yet Germany, Belgium, Gaul, Spain, Hippo, Carthage, Cirta - all fell to them. In 420-440, for example, the Vandals installed themselves in North Africa, cutting off both Roman empires from their primary supply of grain in Egypt.

Weakness invites attack

By then, the Roman West was essentially deadwood, and the Vandals put it to the torch. Their king even spent two weeks in Rome in 455 plundering at will, stripping the gilded roof of the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus. And shortly before, in 440-450, Atilla the Hun had ravaged Europe without effective interference from Roman armies.

It is said that the Huns invading Greece decided not to torch the libraries because they decided that while the Greeks were reading books they would not be making conspiracies against the Huns. They knew bookworms couldn’t fight barbarians.

The East Empire mounted one unsuccessful naval expedition against the Vandals in 468 and finally defeated them in 533 with an army of only 17,000 men - but only after the Vandals had themselves fallen into decadence, weakened by creature comforts.

So why couldn’t the Western Empire - previously capable of assembling armies of 200,000 men - defend itself against such small forces?

Fertility and Falling Cultures

‘Childlessness prevailed,’3 according to Tacitus. And Pliny the Younger lamented how ‘even one child is thought a burden preventing the rewards of childlessness.’ Immigrants replenished the ageing population to augment the workforce and maintain taxation but failed to fully integrate, leading to internal aliens.

Remember: under the republic, only Roman citizens had been admitted to fight in the army. But late in the empire the army comprised largely foreigners and mercenaries: the higher officers were practically all Germans. The Eastern Empire, by contrast, survived 1,000 years longer, and there the aristocratic houses of Constantinople maintained their own military traditions.

The “barbarian” armies were thronging with veterans returning from Roman service, and many of their leaders had held Roman commands. Alaric, who led the Gothic sack of Rome, had himself served as a unit commander under Emperor Theodosius I, only returning to lead the Goths when the Romans denied him promotion to general.

The barbarians also had iron plows, steel swords and battle-axes far superior to those of the Romans. By contrast, the effeminacy and depravity of the emperors is captured by Gibbon’s comment that Gallienus was ‘a ready orator, an elegant poet, a skilful gardener, an excellent cook, and most contemptible prince’.

Skin in the Game

And whereas the ideal Roman citizen-soldier had previously been able to serve close to home, returning to his wife, family and fields, soldiering in the latter days of the empire was a year-round, far-away affair. Increasingly, the Western Empire made the fatal mistake of surrendering control of its military to people without a significant stake in the society they were defending.

The barbarian invasions merely lifted the lid on the unrest already present. Rome’s regressive taxation meant the rich paid less. Provincial tax collectors also notoriously collected for themselves, and the army was regularly quartered on villagers. There were special taxes for every new emperor and every five years, and eventually tax exhaustion meant amnesties had to be granted.

Rome begged people to go back to the soil to produce crops. There were frequent complaints from the rural poor. Forced to stay on the soil as serfs, they often joined the barbarians, and there was a reemergence of the local traditions stifled under enforced Romanisation. The governors of the state had made almost no effort to win the loyalty of the people on whom they depended for defence of the social structure.

The West’s attempt to assimilate the barbarian tribes hadn’t worked. German tribes were given a third of the yield of the provinces they were defending - or a third of the land, sometimes even two-thirds. This had the advantage that the proprietor kept his life and wife, but it created a multilingual, multiracial and disgruntled society.

And even worse was the method adopted during the Italian reign of Theodoric. There the civil administration was entirely Roman, but the military was entirely handed over to the Ostrogoths. This led to thirty-three years of ease, leaving them totally unprepared for the Vandals.

The Eastern Empire was more successful. Valens had subdued then expelled them. He admitted them only if they disarmed. Although he refused admission to the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, they entered anyway, weakening him. So he rounded up and killed all the hostages he’d taken when they became threats. And they were finally expelled when Arcadius imported the rough Isaurians from what is now Southeast Turkey: they forced the Ostrogoths to move to Italy, where they eventually killed Odoacer.

The Eastern Empire used its own people for its armies. It gave tax privileges for military liability and focused on small units, giving commanders relative autonomy in their leadership of men they had recruited personally. Minimum bloodshed was the goal.

Confidence and Exhaustion

Like the Western Empire, the Eastern Empire didn’t reach far down enough into the labouring classes or far out enough into the provincial countryside. This meant it, too, eventually became obsolete and feeble. But it lasted a thousand years longer. And unlike the Western Empire, it never acquiesced in its own destruction.

The last of the emperors, Constantine XI, could not even afford a coronation. But with only 8,000 troops, he died defending the imperial city against 200,000 attackers for 53 days, falling in the streets among his men, like the Spartans. In Steven Pressfield’s Gates of Fire, Dionekes says, “you have never tasted freedom, friend, or you would know it is purchased not with gold, but steel.”

As Kenneth Clark explained in Civilisation, the real reason Rome collapsed is that ‘it was exhausted’. Above all, he stressed, ‘civilisation requires confidence in the society in which one lives’. But when the historian Priscus travelled to the court of Atilla deep in the dark forests north of the Danube in 448, he met a renegade Greek. Dressed as a Scythian, this Greek deplored Rome: the benefits of its civilisation, he complained, weren’t worth the costs.

The reason a falling fertility rate is one of the strongest signs of decadence is that it means men, responsible for protecting the perimeters of civilisation - without which no cultural flourishing is possible - literally have less skin in the game. Like Priscus’s renegade Greek, they retreat to the marshes and forests, frogs waiting for the kiss of the feminine to integrate and transform them.

As early as 131BC, the Censor recommended making marriage compulsory because so many men were opting to remain single, and Augustus’ address regarding population decline to the renegades of his day is just as relevant to today’s renegades:

How otherwise shall families continue? How can the commonwealth be preserved if we neither marry nor produce children? Surely you are not expecting some to spring up from the earth to succeed to your good and to public affairs, as myths describe. It is neither pleasing to Heaven nor creditable that our race should cease and the name of Romans meet extinguishment in us, and the city be given up to foreigners, - Greeks or even barbarians.4

Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol II, Ch.24

Stark, How the West Won (ISI, 2014), p.27

Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome, iii, 25

Cassius Dio, Dio’s Rome (Kessinger Publishing, 2004), Book IV, p.86

Share this post