Part III of ‘The Machine Stops’ explores disengagement from reality through idolatry. Part I showed Vashti blocking her view of Greece, symbolic of the tradition of Western philosophy: ‘No ideas here’. Part II showed how, in an emasculating technocracy, the ‘strong will suffer euthanasia’. Kuno longs for a wife and family but isn’t allowed to reproduce because the Machine fears his type — his ‘atavism’. And now Forster explains how the idolaters try to get ‘beyond facts’.

Two great developments occur: respirators are abolished, and religion is reintroduced. And Forster portrays totalitarianism as ultimately directed by people’s desires because these developments ‘did but express tendencies that were latent already’. The Machine just gives people what they want — good and hard.

One of ‘the most advanced’ of the lecturers warns against going to the surface of the earth:

‘Beware of first-hand ideas!…First-hand ideas do not really exist. They are but the physical impressions produced by love and fear, and on this gross foundation who could erect a philosophy? Let your ideas be second-hand, and if possible tenth-hand, for then they will be far removed from that disturbing element – direct observation…And in time' – his voice rose – 'there will come a generation that had got beyond facts, beyond impressions, a generation absolutely colourless, a generation seraphically free from taint of personality, which will see the French Revolution not as it happened, nor as they would like it to have happened, but as it would have happened, had it taken place in the days of the Machine.’

‘Gross’ suggests reality is too coarse — too carnal — for the lecturer’s pride. To be human, in fact, is to suffer the ‘taint of personality’. It’s contamination and corruption. Instead, he wants to be ‘seraphically free’ from it, meaning angelically. They fled from nature because they couldn’t master the sun (an affront to their pride). Now they flee from human nature, too.

And ideology means theory now begins to determine reality: they don’t study how the French Revolution actually happened but only how ‘it would have happened, had it taken place in the days of the Machine.’ This is idolatry, as Forster makes clear from how ‘no one could mistake the reverent tone in which the peroration had concluded’. It’s a religious sermon.

Man can’t escape worshipping something because that’s what he’s made for. Hence the lecturer finds ‘a responsive echo in the heart’ of each of his listeners:

‘Those who had long worshipped silently, now began to talk. They described the strange feeling of peace that came over them when they handled the Book of the Machine…the ecstasy of touching a button…the Machine is omnipotent, eternal; blessed is the Machine.’

Man, as Dostoevksy said, must bow down to something.

And yet ‘the word “religion” was sedulously avoided despite only ‘retrogrades’ not worshipping the Machine as ‘divine’. Ironically, the people, so sophisticated in their own minds, have been snared by idolatry while trying to avoid worship. (‘Sedulously’ comes from the Greek ‘dolos’, meaning ruse or snare.) And it happened through pride:

‘Humanity, in its desire for comfort, had over-reached itself. It had exploited the riches of nature too far. Quietly and complacently, it was sinking into decadence, and progress had come to mean the progress of the Machine.’

Their comfort is their curse because man is saved only via the Cross. Hence Vashti ‘believed she was growing more spritual’ yet ‘did not much mind’ when her friends died, and ‘she would sometimes ask for Euthanasia herself’. She suffers from acedia or sloth: as the Psalmist says, ‘Their soul abhorred all manner of meat.’ (Psalm 106:18)

Yet still she cannot imagine the Machine could ever stop, so when Kuno tells her it’s stopping she says his remark ‘would be impious if it was not mad.’ And Vashti’s friend says, ‘The phrase conveys nothing to me.’ The Machine is their reality, so even when signs of its breakdown finally become apparent — the ‘mouldy artificial fruit’, the ‘bath water than began to stink’ and the ‘defective rhymes that the poetry machine had taken to emit’ — they ignore them:

‘the human tissues in that latter day had become so subservient, that they readily adapted themselves to every caprice of the Machine.’

This image of the ‘subservient’ body reminds us of how ‘each infant was examined at birth, and all who possessed undue physical strength were destroyed’. Kuno, who trained himself to recover the strength to journey to the surface, isn’t allowed children because his type isn’t one the Machine wants to pass on.

Yet after the failure of the sleeping apparatus ‘the discontent grew, for mankind was not yet sufficiently adaptable to do without sleeping.’ They are, after all, creatures humbled by the body — not the seraphim they aspire to be. But ‘the Committee of the Mending Apparatus now came forward, and allayed the panic with well-chosen words.’ Through words the Devil ensnared Eve, and through words the Machine ensnares man:

‘Under the seas, beneath the roots of the mountains, ran the wires through which they saw and heard, the enormous eyes and ears that were their heritage, and the hum of many workings clothed their thoughts in one garment of subserviency.’

Only man, the rational animal, possesses language because it’s a sign of his intellect, part of the image of God in him, from which comes his capacity for abstract thought. But the corruption of the highest becomes the lowest, and what is rightly ordered towards freedom in the Word becomes a disordered ‘garment of subserviency’. Had he been strong enough, Kuno would have gone to the surface ‘naked’.

When the Machine finally stopped, ‘with the cessation of activity came an unexpected terror – silence.’ Many thousands of people died instantly. ‘The steady hum’ of the Machine, having surrounded them since birth, ‘was to the ear what artificial air was to the lungs.’ Addiction to the Machine has weakened them. Although Vashti survived the silence, ‘agonizing pains shot across her head.’

Yet this silence ‘behind all the uproar’ is ‘the silence which is the voice of the earth and of the generations who have gone.’ Kuno was strong enough to survive it even though he says it ‘pierced my ears like a sword.’ It is an echo of ‘the three stars hanging’ that Kuno thought looked ‘like a sword’, reminding him of the time when ‘men carried swords about with them’ — a time when men knew the bill for freedom must be paid in blood.

But it is too late now. Echoing the ‘long white worm…gliding over the moonlit grass’ in the glade when the Mending Apparatus came to pull Kuno back down into the Machine, ‘a tube oozed towards [Vashti] in serpent fashion.’ As the darkness fell, ‘she knew that civilization's long day was closing.’ Man has fallen through comfort, and Vashti realises too late that some kind of sacrifice is necessary to make amends:

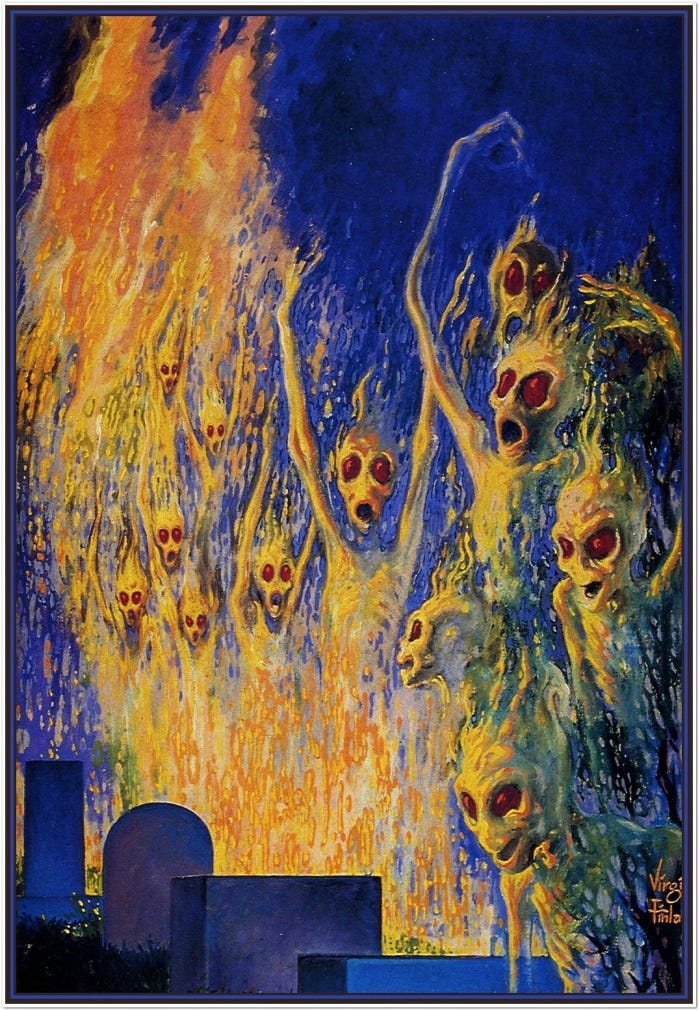

‘Vashti continued to whirl, like the devotees of an earlier religion, screaming, praying, striking at the buttons with bleeding hands. It was thus that she opened her prison and escaped – escaped in the spirit: at least so it seems to me, ere my meditation closes.’

This dervish allusion juxtaposes cuttingly to her sophisticated image of herself as being so refined, civilised and advanced that she doesn’t need religion. And the narrator’s closing description of his story as a ‘meditation’, echoing his use of the same word at the beginning, points to this as material for contemplation, not mere diversion.

Civilisation, as T. S Eliot says, dies not with a bang but a whimper, and Vashti was surrounded by ‘little whimpering groans’ as people ‘were dying by hundreds out in the dark’:

‘Beautiful naked man was dying, strangled in the garments that he had woven…The sin against the body – it was for that they wept in chief; the centuries of wrong against the muscles and the nerves, and those five portals by which we can alone apprehend – glozing it over with talk of evolution, until the body was white pap, the home of ideas as colourless, last sloshy stirrings of a spirit that had grasped the stars.’

The ‘five portals’ of the five senses echoes the ‘advanced’ lecturer’s attempt to ‘get beyond facts’ and ‘first-hand impressions’ because they are too gross. Man, however, is an embodied creature, not an angel. As Aquinas said, ‘Nothing is in the intellect that was not first in the senses.’ Using the intellect, man abstracted from the senses and soared with ‘a spirit that…grasped the stars’, but the attempt to rise above the body, denying it, has left it ‘white pap’ — an echo of Vashti’s ‘lump’ of flesh at the beginning.

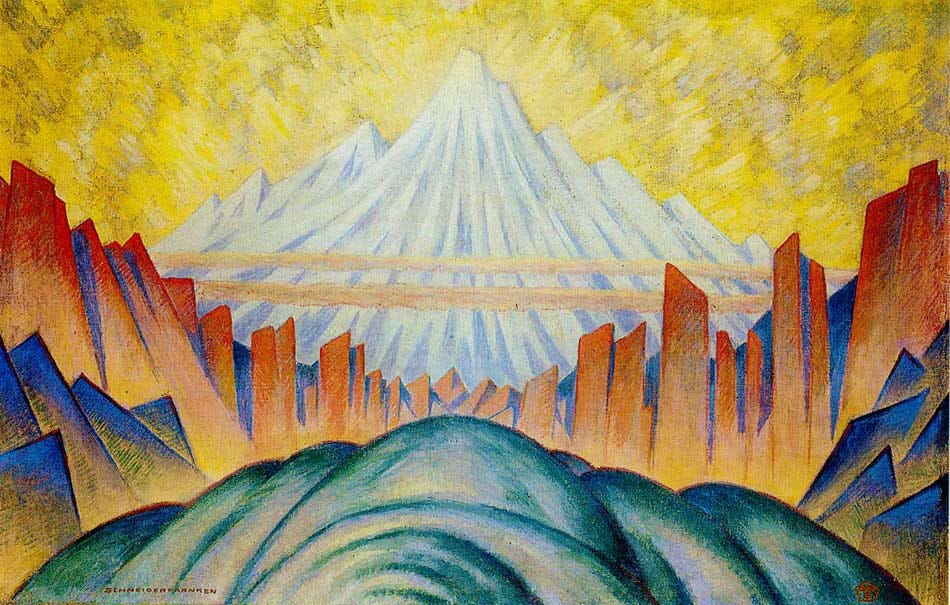

For Kuno, however, ‘we die, but we have recaptured life, as it was in Wessex, when Ælfrid overthrew the Danes. We know what they know outside, they who dwelt in the cloud that is the colour of a pearl.’ Echoing the image of the pearl in the Bible (and Muslims, too, refer to the pearl as a symbol of heaven), this suggests only suffering forms spiritual beauty. Ælfrid did not sink into decadence.

Vashti fears that ‘some fool will start the Machine again, tomorrow.’ But Kuno confidently replies, ‘never. Humanity has learnt its lesson.’ And the final image is of the Machine being ‘broken like a honeycomb’ as an ‘air-ship…sailed in through the vomitory into a ruined wharf.’

This pointedly recalls the opening description of Vashti’s room as being ‘like the cell of a bee’. And the air ships earlier in the story were a symbol of man’s pride as he attempted to outpace the sun, crashing like Icarus. Now they are the final symbol of his fall: ‘It crashed downwards, exploding as it went, rending gallery after gallery with its wings of steel.’

Yet the concluding image of the ‘scraps of untainted sky’ that Vashti and Kuno see before joining the ‘nations of the dead’ offers an image of the beauty of what Augustine called the book of Nature as the book of the Machine burns:

‘there is a great book: the very appearance of created things. Look above you! Look below you! Note it. Read it.’

Interesting, this idea about the pearl as John Steinbeck wrote "The Pearl"- and that story seems in essence this mysticism you describe that is in the Bible and Muslim faith. John Steinbeck's literary Canon was about the rustic "salt of the earth" working class types- their trials, tribulations, and many evils. Was he talking about the potential pearls of society? I feel there's an idea here. Also all of this you are discussing resonates with C.S. Lewis work "The Abolition of Man." It seems there was a lot of threads in this exploration then- T.S. Eliot's "The Wasteland," and the above mentioned works. It seems like the Victorian and Romanticism Eras were at a very sudden and intense clash with the new ideas of industrialism. And then around the time of the free love movement- the counter culture with Woodstock machines were beginning to be seen as wondrous and beneficent portals of opportunity and evolution. I think Star Wars may have helped really cement a love for the machine- after all it did mix a very potent cocktail of the wonders of technology, diluted spiritualism, and a very easy and non offensive "Hero's Journey" of Joseph Campbell, which later became a model to every hero story. I don't know- much of this is me speculating and I could be wrong.