Women are increasingly identifying as witches. Do you want ‘salt scrubs to wash away patriarchal bullshit’? Just ask Ariel Gore, whose witchcraft manuals can give you them. As Chesterton observed, the ‘black magic of witchcraft has been much more practical and much less poetical than the white magic of mythology’.1

What’s happening? Grimm’s Fairy Tales, first published today in 1812, offers some insights. As Maria Tatar observes, ‘sex and violence…are the major concerns of the tales’.2 And just as the nuclear family provides each tale’s main cast of characters, the family itself is the most common subject.

These stories are timely because they are timeless. Tolkien knew their profundity: “to ask what is the origin of stories (however qualified) is to ask what is the origin of language and of the mind."3 That is why only the Bible and the Qur’an have been translated more times.

They have often been censored, starting with Wilhelm Grimm himself, who toned down their frankness about sex. And that tendency is growing today, especially among feminists who want to kill ‘princess culture’. But as Dr. Johnson wisely observed, ‘babies do not want to hear about babies’. They like stories that can ‘stretch and stimulate their little minds.’

The fairy tale does this because, as Mercia Eliade explained, it ‘transposes the initiation process into the sphere of imagination.’ Its imagery is what anthropologists call ‘mythical,’ relying on universal metaphors expressing fundamental realities, often combining physiology and cosmology. Lévi-Strauss regarded this use of symbols as an element of the analogical mode of thought he called the “savage mind.”

Proceeding on enlightenment and rationalist principles, Locke and Rousseau rejected fairy tales. Richard Dawkins, one of their modern intellectual descendants, says that growing up involves forgetting fantasy. But as C. S. Lewis pointed out, you can get realism of content without realism of presentation: the two are independent.

‘A true fairy tale,’ said the German Romantic Novalis, ‘must also be a prophetic account of things.’ But isn’t a ‘true fairy tale’ a contradiction in terms? A square circle? No. Broadly, there are three theories of truth: the correspondence, the coherence, and the pragmatic theories. Confusion about these causes confusion about not just the nature of fairy tales but the nature of literature.

The correspondence theory entails fitting the facts of external reality. I might claim the sky is falling, but is it really? The coherence theory entails being logically consistent. Although it contradicts reality, the madman’s psychosis might not contradict itself. The pragmatic theory says something is ‘true’ if it somehow works politically or socially. It can be ‘true’ for me but not for you.

Fairy tales, Dawkins and their other detractors claim, are at best logically consistent - the coherence theory of truth - but don’t correspond to the real world in any way. Similarly, Tolkien’s fictional world, on this view, achieves only internal coherence but doesn’t tell us anything about reality.

But as Claude Lévi-Strauss said, animals are ‘good to think with’: despite being fantastic in presentation, fairy tales are realistic in content. Like all great literature, they use language in the ways in which the intellect tends to grasp the highest concepts: metaphor, simile, symbolism, analogy. As Petrarch asked, ‘what is theology, if not poetry about God?'

Throughout their various editions, the Grimms’ preface always begins with a description of gleaning. This metaphor, with its religious roots of gathering grain, implies not only searching and gathering but finding out. The Grimms combined Classical Greco-Roman, Norse-German and Biblical poetic tales all aimed, as Max Luthi noted, at answering the fundamental question, ‘what is man?’

Fairy tales provide unsettling answers to this. When the Grimms were first translated and published in English by Edgar Taylor in 1823, the cruellest tales like ‘Snow White’ or ‘The Juniper Tree’ weren’t illustrated at all. And although ogres might live far away deep in the forest, often the worst evil occurs in the heart of the home.

It most often takes the form of wicked mothers, queens and stepmothers. According to Marina Warner, ‘females dominate fairytale evil’.4 Yes, over half the Grimms’ tales feature a young hero. But even ‘The Boy Who Wanted to Learn How to Shudder,’ perhaps the clearest male initiation story, concludes with the boy, having played skittles with skulls and bones, learning fear only when his young wife pours a bucket of fish over him in bed.

What explains this fascination with the feminine? Looking at the content of paranoid delusions and dreams according to sex, men's feature groups of unfriendly male strangers; women’s, by contrast, feature familiar women. In this sense, fairy tales are warning sirens. The archetypal Wicked Stepmother or Ugly Sisters correspond to important elements of reality.

In all societies, for example, there is a tension between the husband's mother and her daughter-in-law. 90% of recorded instances of female aggression worldwide are against other women, and sexual rivals are the frequent victims. Even in societies with sororal polygyny, at least 20% of co-wife aggression is between sisters. (In King Lear, Goneril poisons Regan over Edmund.)

Female relational aggression is central to fairy tales. Suzannah Lipscomb writes that ‘in most places in Europe women made up the vast majority of those who were prosecuted and executed as witches’. But most accusers were women, and the fewer women involved in the trials, the fairer the treatment witches were likely to receive.

So ‘fairy tales provide vitally helpful messages that parents could be discussing with their girls’, Amy Alkon reminds us. Consider Snow White, perhaps the Grimms’ masterpiece. The opening is arrestingly beautiful and profound:

Once upon a time in the midst of winter as the snowflakes were falling like feathers from heaven, a queen sat at a window which had an ebony frame and sewed. And as she was sewing, she looked up at the snow and she stabbed herself in the finger with the needle and three drops of blood fell onto the snow. And since the red looked so beautiful in the white snow she thought to herself, "I wish I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood of the window frame." Soon thereafter she had a child which was as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black-haired as ebony wood, and therefore was called Snow White. And as the child was born the queen died.

Snow White's mother wishes for a child red as blood (loving and warm), white as snow (pure and spiritual) and black as ebony wood (earthy, connected to the tree of life). But such beauty has a price: ‘as the child was born the queen died’. Motherhood involves sacrifice. In decadent Rome, many women avoided childbirth because they feared losing their looks.

But Snow White’s stepmother can’t stand her beauty. Unlike a painting produced to please her, the mirror tells her the truth: learning that Snow White is ‘a thousand times fairer’ than she is, ‘the queen took fright and turned yellow and green with envy’. In contrast to Snow White's red, white and black, the green and yellow queen is jealousy incarnate. She can tolerate no rival.

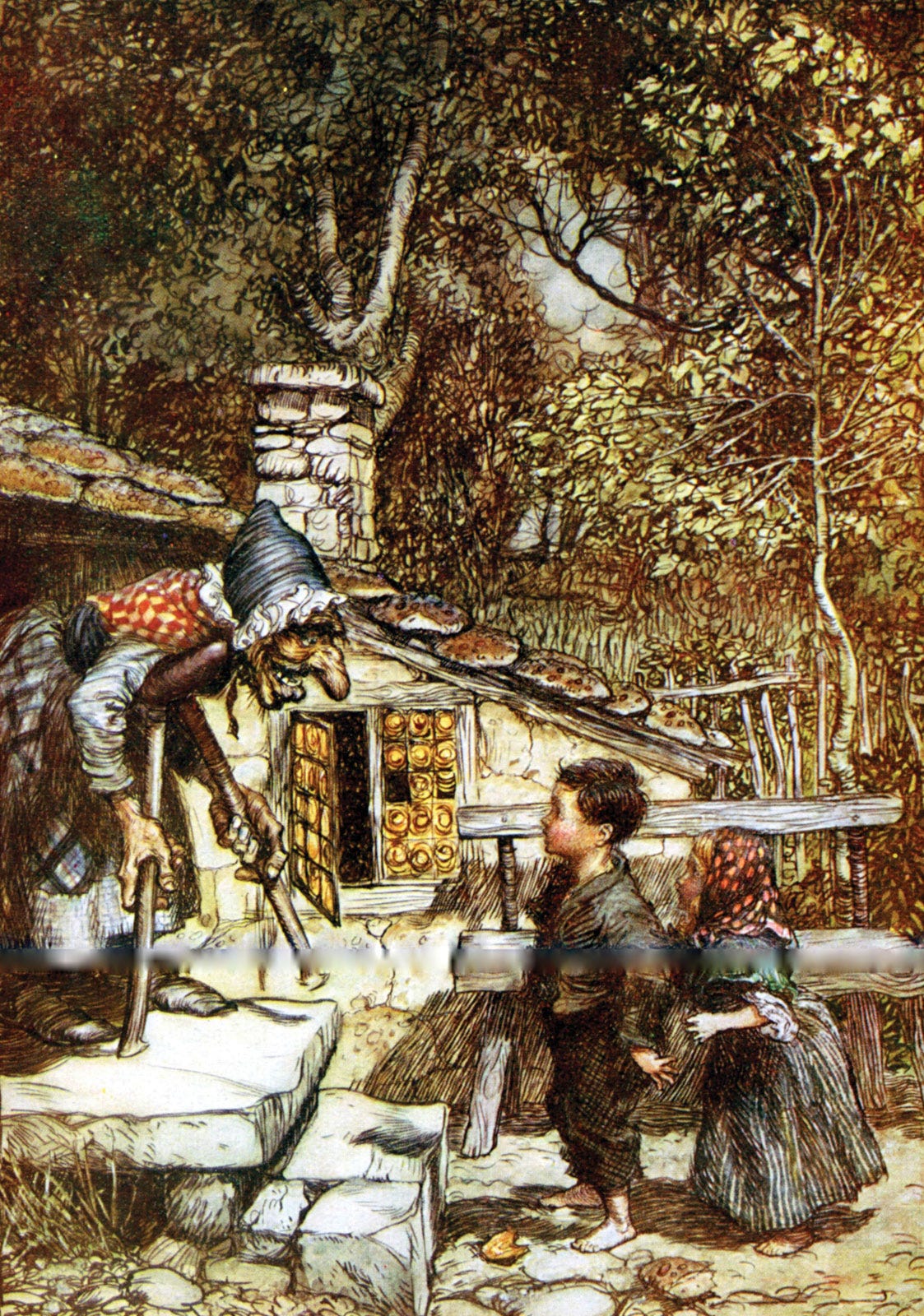

She orders the huntsman to kill Snow White and ‘bring her lungs and her liver back to me’ because she wants to eat them. She desires to incorporate Snow White's magic beauty into herself; there is a connection here to the cannibalistic witch in Hansel and Gretel. Both are inversions of the feminine: Snow White’s mother sacrifices her life and beauty, whereas these perversions of femininity kill.

Satan was created as the angel Lucifer ("light-bearer"), second only to God in beauty. He fell because he was so infatuated with this own beauty that he could tolerate none above him. ‘You, my queen, are fair,’ admits the mirror. But that isn’t enough. She has to be the most beautiful in ‘the land’.

In Bettelheim’s reading, the queen, disguising herself, then plays the satanic role of the tempting serpent. This is a deep insight. The queen aims at tricking Snow White into accepting her own concept of beauty. Being naturally a thousand times more beautiful than the queen, Snow White has no need for the queen’s offers. But like Eve she is not content.

And so tightening the bodice suffocates her soul. The more she combs her hair with the black comb, the more poison it transfers. And most chillingly the poison of the red apple tempts her to see beauty as something that can be eaten, just as her stepmother tried to eat her. It encourages her to see her ‘red’ warmth as mere sexuality.

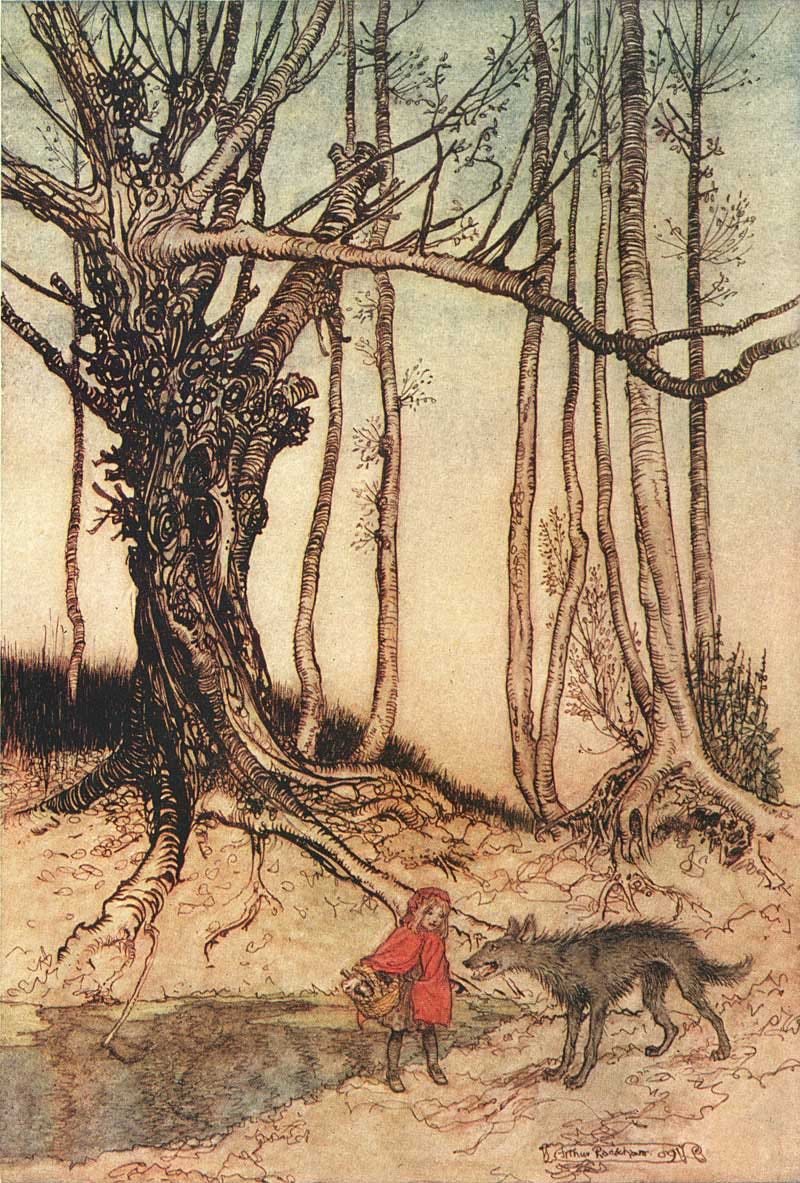

Like the queen and like the witch in ‘Hansel and Gretel’, the wolf in ‘Red Riding Hood’ is also a devourer. It is commonly read as an initiation into sexuality. Bettelheim, for example, saw Little Red Cap’s danger as her budding sexuality, for which she is not yet emotionally mature enough.

However offensive feminists might find the fact, rape is one of the most common female fantasies. And ‘rapture’ and ‘rape’ are etymologically connected. ‘Rapture’ as an ‘act of carrying off’ as prey or plunder comes from the Latin raptus "a carrying off, abduction, snatching away, rape”. It is also used in the sense of "spiritual ecstasy, state of mental transport or exaltation”.

‘The Beauty and The Beast’ is the archetype of women’s desire not just to tame the beast in men but for their beauty to render men beasts overwhelmed by desire. And it persists throughout literature. In A Streetcar Named Desire, Stella explains her reconciliation to Stanley’s crudity by saying that ‘there are things that happen between a man and a woman in the dark - that make everything else seem - unimportant’.

Angela Carter saw the opportunity for sexual liberation here, concluding her version with Little Red Riding Hood ‘tucked up between the paws of the tender wolf.’ But the Grimms’ tale is deeper than that. The wolf is also the jaws of death. The wolf has often been a symbol of the Devil. As Luther said, Christ ‘rips the sheep out of the jaws of the wolf, that is, the devil.’

The Grimms’ wolf has a ‘terrible big mouth,’ as does Fenrir, the wolf of Norse myth, whose jaws devour the entire cosmos at Ragnarok. The wolf, then, is chaos threatening to devour order - not just Little Red Riding Hood but her grandmother, too, symbolising her ancestors. This is why below the grandmother’s oak trees (sacramental as the place of sacrifice to Woden) are poison hazel nuts, as the wolf - Woden’s great adversary - ‘must know’.

There is deep religious symbolism here. According to G. Ronald Murphy, ‘Fenrir, the cosmic wolf of night, blends with Cronos, god of time, and Christ puts on the clothes of a hunter and performs the task of Zeus to overcome time and the belly of the beast, not to save fellow gods, however, but to save the red-capped human soul.’5

Like the witch, the wolf is a devourer. Chesterton speculates that black magic has a practical attraction ‘because the Fall has really brought men nearer to less desirable neighbours in the spiritual world’.6 Generations of readers, for example, have fallen under the spell of Milton’s Satan: we have more in common with him than we do with the angels.

But witches were most commonly seen, Chesterton adds, as preventing the birth of children. ‘Running through [black magic] everywhere,’ he observes, is ‘a mystical hatred of the idea of childhood’.7 And today the annual bodycount of abortion dwarfs that of the Holocaust, while the developed world, especially Europe and America, falls further below the fertility replacement rate.

Marina Warner points out that ‘parsley, not rampion, is the herb that gives the heroine her names (e.g., Persinette) in the Italian and French variations of the fairy story which predate the Grimms’, adding that ‘parsley, when decocted in concentration, was a popular abortifacient.’ It grows in the witch's garden.

Perhaps this is the reason for the attraction to witchcraft today. If so, even the most gruesome Grimm tale, ‘The Juniper Tree’, offers hope. A stepmother decapitates her stepson then feeds him to his unknowing father. But when the sister buried her murdered brother’s bones with his mother’s beneath the tree,

it began to move. The branches separated and came together again as though they were clapping their hands in joy. At the same time smoke came out of the tree, and in the middle of the smoke there was a flame that seemed to be burning. Then a beautiful bird flew out of the fire and began singing magnificently.

This symbolises the true association of the feminine with fertility and life, not the terrifying ‘dead, dried out’ hand of the witch in Hansel and Gretel. Like the hand of Snow White's wicked stepmother, that ‘dead, dried out’ hand reaches out from modern culture to tempt girls away from themselves - unless they read fairy tales.

Everlasting Man (Dodd, Mead and Company, 1925), p.163

The Hard Facts of the Grimms Fairy Tales (Princeton, 1987), p.35)

"On Fairy-Stories," in Essays Presented to Charles Williams (London: Oxford University Press, 1947), p. 47.

Fairy Tale: A Very Short Introduction to Fairy Tales (OUP, 2018) p.52).

The Owl. The Raven and The Dove (Oxford, 2000), p.83.

Everlasting Man (Dodd, Mead and Company, 1925), p.163

Ibid, p.169

Beautiful. Thank you for writing this.

There is a deep connection between fairy tales and the nature of national identity, too. The Zollverein states of Germany were buoyed by the Grimm's fairy tales and Johann Gottlieb Fichte's Addresses to the German Nation, strongly tied land and history to its people.