‘Wherever an altar is found, there civilization exists,’ wrote Joseph de Maistre, and Alexander Boot’s How the West was Lost diagnoses the disorder of modernity as ultimately spiritual. As what Schopenhauer termed the metaphysical animal, man seeks in vain for political or economic cures. This article is a summary of what I consider to be Boot’s most salient points, along with my commentary on them.

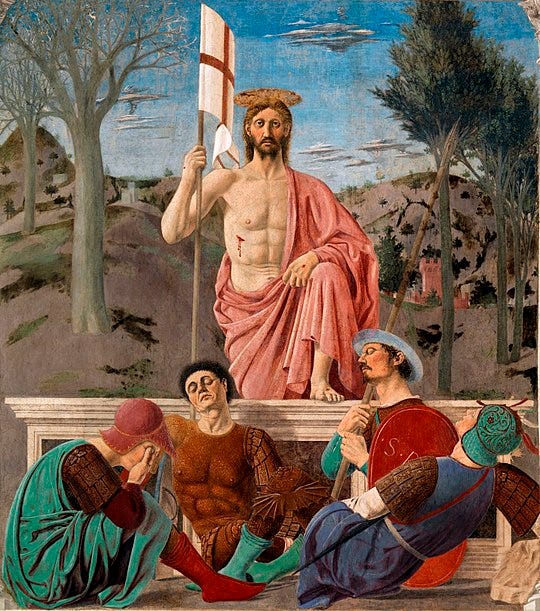

According to Boot, the modern world results from a revenge-driven attack by ‘Modman’ - civilization’s internal barbarian - on the Christian tradition of ‘Westman’. Since the two prongs of Modman’s attack, nihilism and philistinism, are ultimately doomed to fail, Boot argues that it behoves all those who would oppose it to ‘keep vigil over Westman’s treasure’. As Christianity was founded on the ruins of Rome, so from the wreckage of Modman’s project will arise a ‘revived and rejuvenated Westman, a Lazarus brought back from the dead, a light reignited to blind the infidels yet again with the glory of transcendent beauty.’

That, in essence, is Boot’s thesis. It recalls T. S. Eliot’s ‘Thoughts After Lambeth’ (1931):

‘The World is trying the experiment of attempting to form a civilized but non-Christian mentality. The experiment will fail; but we must be very patient in awaiting its collapse; meanwhile redeeming the time: so that the Faith may be preserved alive through the dark ages before us; to renew and rebuild civilization, and save the World from suicide.’

Though the night of Eliot’s prophesied dark ages thickens still, in a dark time the eye begins to see, and Boot offers trenchant insights into both the causes and consequences of our cultural decline.

Free Will and the Reality of Good and Evil

For Boot, Westman’s ‘founding animus came from an all-consuming, introspective need to understand Christ’s message, to express this understanding by every means, mostly artistic, and to fashion a society that would encourage and reward a life-long spiritual quest.’ Boot is a precise writer, and animus here is used in its strict sense of ‘temper,’ indicated etymologically by the Latin animus, ‘rational soul’. Free will and rationality stand or fall together: free choices are rational. Whereas most ancient societies believed in fate, Westmen believed, as Boot explains, that ‘choices made by their free will could either save or destroy their soul’. Free will was more than merely abstract philosophy: the Ten Commandments presupposed it. The soul would be judged based on its choices. ‘Free individual choice between good and bad,’ Boot points out, ‘is the basis of Western culture as much as the choice between good and evil is the bedrock of Western religion.’

As the ‘founding animus’ of Westman, Christ’s message brought to fulfilment the best of the classical culture of Greece and Rome. The strength of Boot’s narrative is that he shows how Christianity is pivotal in that, having done this, it was then opposed by the Enlightenment. He thus involves all three of the main strands of Western civilization typically identified by scholars: (1) Greece and Rome, (2) Christianity and (3) the Enlightenment. But Boot rightly emphasises the centrality of Christianity: as Christopher Dawson put it, ‘no one has any right to talk of the history of Western civilization unless he has done his best to understand its aims and its methods.’

Christianity’s assimilation of classical culture is illustrated by one of the early Church fathers, Justin Martyr (ca. 100–165). Born into a Greek-speaking pagan family, he still wore his philosopher’s cloak after his conversion to Christianity in 130 and considered the Jewish prophets and Greek philosophers ‘Christians before Christ.’ Plato, he believed, had laid the foundation for Christianity: God was outside the universe, timeless, and immutable. Because Greek philosophy recognised man’s divine gift of reason, it also recognised the reality of free will, and Justin saw Christ as the personification of ‘right reason’. Indeed, Boot argues that, ‘if one had to express the essence of Westman in a sentence, no other set of words could come close’ to ‘The kingdom of God is within you’.

If liberty was the Greek heritage, the Roman heritage was law. In the Aeneid, for example, Anchises’s shade, speaking to his son Aeneas, tells him that, although others will exceed the Romans in the arts, the Romans will “impose their rule on the peoples (these will be your arts) and add settled custom to peace, to spare the conquered and cast down the proud” (Aeneid 6.851–53). Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations also claims Rome is distinctive in this regard. Thus Remi Brague’s Eccentric Culture: A Theory of Western Civilization (1992, trans. 2002) argues that Rome mediated the Greek and Judaeo-Christian traditions.

Liberty and law: by stressing the sanctity of the individual believer (souls are immortal, but states aren’t) and the need for submission to a higher authority (Christ) than any secular one (Caesar), the Roman Catholic Church’s struggle against the Holy Roman Emperor refined the concept of liberty under law and the separation and limitation of powers.

Culture and Internal Barbarians

Thus the kingdom of God was not only within but also manifested without: ‘the most visible part of Westman’s soul is its ability to produce culture.’ Non-rational animals lack culture. People claim dolphins, for example, are intelligent, but dolphins don’t compose symphonies or build cathedrals. By contrast, human culture constitutes the pattern of life and thought into which each generation is initiated. Accordingly, ‘the culture of Westmen was intertwined with the way they viewed the world,’ Boot reminds us. He writes movingly of how ‘people who would catch a glimpse of the West across a castle moat or hear an echo of it through a concert-hall door.’ George Steiner, in explaining why Middlemarch falls short of the status of, for example, The Brothers Karamazov, remarked that ‘the only way for art to pass into universality is for it to attack on a metaphysical front’. Transcendent art is religious.

And the most transcendent art of all, Boot argues, is music: ’the quintessence of Western culture’. For Plato, music moved the soul, and Boot points to Bach as the epitome of its power. Unlike modern celebrities, he wasn’t glorifying himself; he was glorifying God. That is why Boot says ‘the greatest achievement of Western civilization in the arts, certainly in music and painting, preceded the Enlightenment.’ But such is the power of music that it has also been weaponised to attack Westman’s tradition. Accordingly, ‘pop music exists to express the true nature of Modmen’: their hatred of Westmen. Indeed, ‘mass vulgarity thus has succeeded where the Crucifixion failed: Christ is now dead, at least as a social force.’

The reason for this hostility, he believes, is that, ‘as Christian culture grew more sublime and consequently more exclusive, Christendom became more vulnerable.’ Why? Essentially, it’s because ‘culture’s meat is civilization’s poison and vice versa.’ Those unwilling to put in the heroic effort demanded by the ‘lifelong spiritual quest’ at the heart of Westman’s tradition increasingly became internal barbarians. It presented itself as the easier option. Concupiscence, after all, means fallen man inclines towards disorder. I recall a young student once remarking, when discussing why Shakespeare’s tragedies are more popular than his comedies, that ‘there’s not much love around.’ Thus ‘the vanquishing civilization, rather than coming from a remote continent, grew to maturity within the West itself’. And ‘no marriage is possible between Christendom and the internal barbarian.’

The Reformation

This crisis, Boot believes, underpinned the Reformation. ‘Detrimental to Westman’s health,’ the Reformation’s ‘shock waves would never become properly attenuated’. Jaime Luciano Balmes, writing in the mid-nineteenth century, remarked that Protestantism did not produce the principle of private judgement but rather was itself the offspring of it. It tried, without success, to limit private judgement but was thereby ‘compelled either to throw itself into the arms of authority, and thus acknowledge itself in the wrong, or else allowing the dissolving principle’ to unfold its logical implications. With this assessment Boot agrees:

‘The Reformation encouraged every man to fashion his own God…The Enlightenment taught him to be his own God…Marxism said the state was God.’

Two aspects of the Reformation are especially significant. First, one of the initial and most fundamental errors of Luther and Calvin was the denial of free will - absolutely central to Westman’s tradition. This removed the burden of weight of making the right choices. Boot notes that ‘Cranmer, in particular, expurgated from his Book of Common Prayer all prayers for the dead because to the Protestants the final posting of the human soul was predetermined from the start, not being sensitive to any good works undertaken during one’s lifetime.’ Second, ‘European countries were no longer just Christian’. Instead, ‘they were either Catholic or Protestant, and their respective churches had to take political sides.’ The Reformation thus instantly led to ‘the politicizing of religion, and for Boot ‘modern means, among other things, politicized’.

Ultimately, ‘what gave Protestantism its great attraction,’ Doellinger wrote, ‘was that its teaching revealed an easier road to heaven.’ Brenz, too, a Protestant writer, admitted that freedom from the obligation of penance and of fasting was what tempted the common people over to Protestantism. And they were quick to identify liberty of conscience - and the new religion itself - with freedom to disregard all ecclesiastical and moral laws. In ‘What is Enlightenment?’ (1784), Kant wrote that it was the “freeing” of the mind from the shackles of tradition and religion.

The Enlightenment

Hatred against Rome, then, was the main cause of the Reformation. As Boot remarks, ‘hatred of the past comes as naturally to Modmen as does their belief in a shining future.’ Modman was ‘born out of a widespread urge to do away with Westman and everything he stood for’.

He is ‘a sociocultural type whose intuitive two-pronged animus comes from a desire to destroy the spiritual and cultural essence of Westman heritage, while at the same time magnifying the material gains that were incidental to that heritage.’

In fact, ‘ever since the destruction of religion, Westman’s material acumen has been growing in inverse proportion to his ability to maintain his culture and civilization.’

This, ultimately, is what makes Modman’s destruction of Westman ‘a hollow victory, akin to an insect causing its own death by stinging a foe.’ In fact, Modman never rationally vanquished Westman. Instead, noting how ‘at some point in the past Westman had curled up and died,’ Modman seized the opportunity to replace ‘God as man’ with ‘Modman as God’.

No man, however, Theodore Dalrymple reminds us in the preface to Boot’s book, ‘can live without a philosophy, whether implicit or explicit’. And so Modman ‘took out of Christianity what he needed and dumped the rest’. Britain’s Glorious Revolution of 1688 stressed liberty and constitutionalism; the French Revolution of 1789, democracy and rationalism. As Boot puts it, whereas ‘Westmen’s individualism leads to respect for the individuality of others’, Modmen ‘are not metaphysical individualists but materialistic egotists.’

Above all, this was evident in the Enlightenment’s idolatry of reason and science. Since the Enlightenment, our civilization has not been Christian. With it, the intellectual elite of Christendom was secularised. As Dostoevsky remarked, however, ’it’s impossible to be a man and not bow down to something. Such a man could not bear the weight of himself.’ Because man is made for worship, science, progress and democracy became surrogate religions. Ironically, even science, proudly regarded by Modman as his greatest achievement, was stillborn everywhere except the Christian West, where the scientific method of investigating nature by means of careful observation and rational inference, leading to a belief in the possibility of progress, resulted from the Judaeo-Christian conception of the world as the work of a rational Creator. Stanley Jaki developed this thesis at length in The Road of Science and the Ways to God (1980).

Christianity thus birthed the best elements of the Enlightenment tradition while subordinating them to a higher Biblical truth. It knew, to use Aquinas’s terminology, that man is a ‘measured measure’ (mensura mensurata), not a ‘measuring measure’ (mensura mensurans). Man is not his own god. Seen in this light, the Enlightenment is merely a manifestation of the ancient temptation ‘ye shall be as gods’, and progress towards what Bertrand Russell termed the ‘shining society of the future’ is driven by pride. (Revealingly, even in old age, Russell refused to stay faithful to his wife.) Rebellion is the heart of revolution, and Aquinas defined pride as the greatest sin: as Boethius observed, "while all vices flee from God, pride alone withstands God”. The queen of all vices according to Aquinas, it was man’s first sin.

‘Every rebellion against the order of man is noble, so long as it does not disguise rebelliousness against the order of the world.’ - Don Colacho

‘Knowledge is power,’ Francis Bacon famously wrote. Although nobody regards him as a great scientist now, he is nevertheless remembered as the prophet of man’s scientific power, as evident in Cowley’s ode ‘To the Royal Society’:

Bacon, like Moses, led us forth at last;

The barren wilderness he past;

Did on the very border stand

Of the blest promised land.

And with Bacon’s belief in both a complete instauration of learning on a new basis and a utilitarian ideal of science as an instrument of human progress Descartes agreed. Men would thereby become ‘the masters and possessors of nature.’ Since French was then the common language of educated Europe, this spirit animated the elite of the day, as it still does today.

And this domination and control over nature of course includes human nature. Boot remarks that ‘the totalitarian scientist wants to extend his domain beyond the natural world and over the spirit, for without such extension his power would be less than total.’ He quotes Ortega y Gasset: ‘By 1890, we find a type of scientist without precedent in history’ — one who wants, Boot says, ‘not just to run people’s lives but to change their nature’. The aim, as expressed by Rousseau, was ‘altering man’s constitution’.

Rival Religions

Although this rationalism is regarded as anti-religious, it is in fact a rival faith. ‘Strictly speaking’, wrote Nietzsche,

‘there is no such thing as science “without any presuppositions”…a philosophy, a “faith”, must always be there first…It is a metaphysical faith that underlies our faith in science.’

To reason at all, for example, is to have faith in reason, which cannot prove itself without assuming what it’s trying to prove. The Enlightenment faith in reason and man’s ability to create heaven on earth by his own power fails to see what Pascal pointed out as reason’s last step: the recognition that there are infinite number of things beyond it.

As Boot remarks, however, ‘polarized thinking comes naturally to unsubtle minds’, and Modman’s mind, seething with hatred for Westman, is as unsubtle as they come. Whereas for Westman, as Pope John Paul II put it, ‘faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth,’ Modman admits reason only. And yet there is a messianic element to Modman’s mission, as manifested in the totalitarian tendencies of Modman’s politics. Each of the three post-Enlightenment substitute religions, as Kenneth Minogue notes in “‘Christophobia’ and the West,” identifies Christianity as the enemy: (1) progress, (2) Marxism, and (3) “Olympianism.” He defines the last as the belief that an enlightened intellectual elite not merely can but should bring about

“human betterment . . . on a global scale by forcing the peoples of the world into a single community based on the universal enjoyment of appropriate human rights.”

Here again, Genesis is illuminating. At the serpent’s instigation, man sinned by wanting to decide what was good or evil for him to do. But Aquinas remarks that man sinned, too, in ‘coveting God's likeness as regards his own power of operation, namely that by his own natural power he might act so as to obtain happiness.’ Christopher Dawson noted that, in American especially, ‘progress’, ‘democracy’ and ‘science’ acquired what a ‘numinous power’. For Boot, too, socialism and communism are Modman’s ‘redemptive creeds’ - indeed, ‘unlimited democracy’s first cousins once removed’. This is because ‘socialism is democracy with logic’, and ‘communism is socialism with nerve.’ He sees ‘socialism as a natural consequence of liberalism, not its denial’ and regards the lasting impact of the Soviet Union as ‘worse than that of Nazism despite the emotional consensus of the West.’

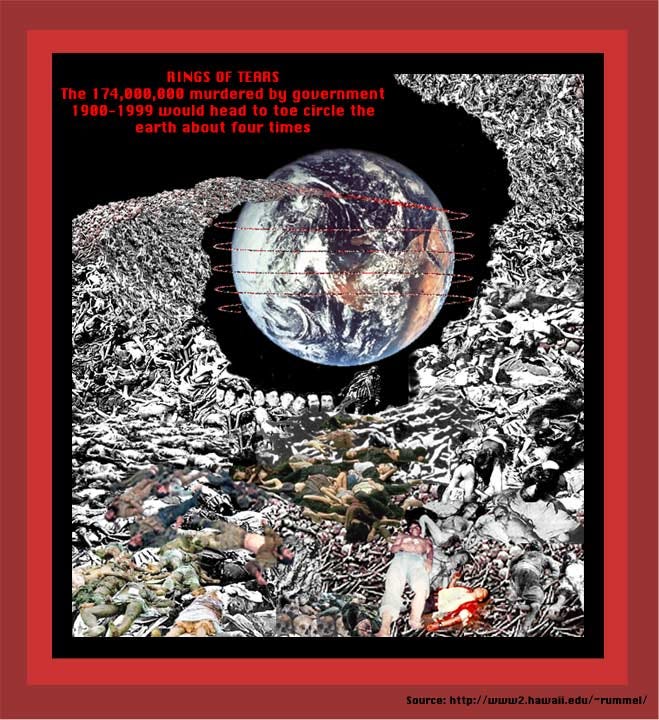

If Bacon saw that knowledge is power, Nietzsche - announcing the death of God - saw that power is domination. In the name of liberation and rationality, then, the modern scientific state becomes totalitarian. Indeed, it desires a universal empire of global governance. The Olympian elites are masters of the globe, and for Boot ‘rumours of the demise of Marxism are exaggerated’ because ‘it is in Modman’s breast.’ And for this reason ‘it will persevere for as long as Modman does’ because Modman is ‘totalitarian by nature’.

The Family and The Future

Hence Modman’s attack on the family — ‘the core unit of Westman society’. The Fourth Commandment is “Honor your father and your mother,” and the Catechism comments that ‘we are obliged to honor and respect all those whom God, for our good, has vested with his authority” (2197). Indeed, here we see in concrete form the passage from the “love of God” to the “love of neighbor,” beginning with the family, which the Catechism calls “the original cell of social life” (2207). From this cell, extended families, tribes and nations develop.

But Boot highlights how ‘the hectoring provider state replaces the loving provider family as the core of Modman’s world; the only thing left for the family to do is to fade away.’ Whereas for Westman ‘the objective of society is to prepare the young for adulthood’, for Modman ‘the objective of the modern state is to keep them perpetually adolescent.’ Boot notes how Turgenev showed in Fathers and Sons that a rift between parents and children natural accompanies a radical onslaught on the family as the repository of tradition and wisdom. Thus ‘the young were urged to hate their families’.

This, Boot observes, is one reason for Modman’s anti-Semitism:

‘The importance of family, a patriarchal organization of society, religiosity governing every aspect of behaviour, a set of religious laws seen to have primacy over any secular regulations – all these characteristics made the Jews unacceptable to Modmen.’

Whereas Christians had sought to convert the Jews, ‘Modman nihilists sought to exterminate them’. Although thinkers on the right often accuse Jews of having caused the West’s cultural crisis, it would be accurate to say Jews, as a nomadic people comprising different ethnicities bound by a strong religious identity, were well-positioned to thrive in it. Throughout history, Jewish advancement to positions of power —in the Reformation, for example — has been a symptom of political and economic upheaval.

And what of philistine Modman? In America, which Boot regards as ‘the first modman country’, he has grown ‘so smug that he no longer honours Westmen with hatred. Derisory laughter is all he can spare.’ But it is likely, Boot argues, that Westman will have the last laugh because history shows that ‘Modman will die by the same hatred by which he lives.’ This is because ‘evil has a life-long lease in the human soul.’ That is the fundamental and fatal error at the heart of Modman’s project. Russell’s ‘shining society of the future’ fails to account for the darkness in man’s heart.

As Helen Pinkerton puts it in her haunting poem ‘On Goya’s Duel with Cudgels’, all attempts to bring heaven down to earth only end up raising hell:

Uncertain light limns hills obscure and sere.

Mired in quicksand thick as the atmosphere,

Two unknown men, who may be son and father

Or riven brothers, raise bludgeons to each other.

Starkly-avowed, this reign of rage and pride,

Of reason’s dream become nightmare and graves,

Makes time thereafter, Goya, seem prophesied:

Heaven not brought down to earth as you dreamed, young,

But hell raised up, an open field for knaves.

‘Reason’s dream become nightmare and graves’: the Enlightenment dream was knowledge as power, but as Burke wrote in A Vindication of Natural Society, ‘power gradually extirpates from the mind every humane and gentle virtue.’ And so, as Albany comments in King Lear,

It will come,

Humanity must perforce prey on itself,

Like monsters of the deep.

Westman, though, is ‘not scared of suffering because it was to a large extent suffering that had made him what he was.’ Westman’s world was founded not on the pursuit of happiness but on Christ crucified. And since ‘it is his soul that made Westman what he was’, Boot argues that 'it is the preservation of his soul that holds a glimmer of hope for his coming back from the dead.’ And so we can insist that ‘words be used in their real meaning’, ‘counter the pernicious effect of Modmen’s schools on our children by teaching them Westman truths’ and ‘hone our minds and tastes to a point where they become worthy of Westman’s heritage.’

Ultimately, he reminds us, ‘no true freedom, be that of enterprise or anything else, is possible without the ultimate discipline imposed by a suprahuman authority.’

'The question is what can be done–what can and what

must be done, because there isn’t any choice.

Whatever we do in the political and social order, the indispensable foundation

is prayer, the heart of which is the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the perfect prayer

of Christ Himself, Priest and Victim, recreating in an unbloody manner the

bloody, selfsame Sacrifice of Calvary. What is Christian Culture? It is

essentially the Mass. That is not my or anyone’s opinion or theory or wish but

the central fact of two thousand years of history. Christendom, what secularists

call Western Civilization, is the Mass and the paraphernalia which protect and

facilitate it. All architecture, art, political and social forms, economics, the way

people live and feel and think, music, literature–all these things when they are

right, are ways of fostering and protecting the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. ' - John Senior, The Restoration of Christian Culture

Great work Will! Superb!!!