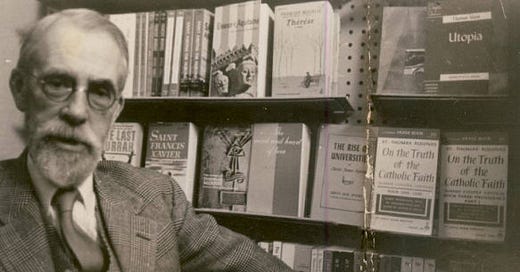

Dawson on The Crisis of Western Education

Surrogate religions strive to fill the spiritual void

According to Christopher Dawson, our culture lacks a common understanding of nature or of man and any transcendent aim for person or society. Each deficiency is serious, and together they constitute the crisis of Western education.

“The world religions,” he said, “are the great spiritual highways that have led mankind through history from remote antiquity to modern times.” (p.121) And the state needs a spiritual bond. Mere law or force will not suffice.

Christianity used to provide the integrating principle, but since the secularisation of western culture three contemporary surrogate religions —democratic, fascist, and communist—have tried to replace it. Although each transcends the individual, none succeeds in transcending either the secular or the temporal.

The secularisation dates not from the Renaissance of Reformation but from the eighteenth-century enlightenment. The humanist educators of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw their devotion to classical culture as compatible with their Christianity. And although the Reformation showed an inherent contradiction between Protestantism and Humanism, the latter was strong enough to survive.

Christian humanism thus saved western culture from disintegration under the forces of religious conflict. And through the vernacular literatures, it came to everyone who could read. Right up to the seventeenth century, educational development in Europe was dominated and unified by the traditions of Christianity and classical culture.

But the ‘scientific utilitarianism’ of Francis Bacon divorced the religious and secular worlds. His ‘distrust of metaphysics and mysticism caused him to draw an unnaturally sharp boundary between religion and science’ (p.38). Bacon, as Dawson described him, was ‘the first man to preach the new gospel of the new philosophy of active science with authority and to assert the necessity of a complete reorganisation of studies on this new foundation’.

Particularly in America, Dawson noted, faith in science supplanted theological orthodoxy and merged unconsciously with faith in democracy. And this culminated in John Dewey’s ‘secular idealism’: ‘the participation of every human being in the formation of social values’ to create ‘the final pooled intelligence’. (p.79)

This, Dawson remarked, was more religious than political. In Dewey’s thought, ‘community’, ‘democracy’, ‘progress’ and even ‘youth’ take on, he said, ‘a kind of numinous power character which gives them an emotional or evocative power and puts them above rational criticism’. (p.80)

Dawson noted an ‘all-pervading influence of the secular standards and values which affects the whole educational system and makes the idea of an integrated religious culture seem antiquated and absurd to the politicians and publicists and the technical experts who are the makers of public opinion’. (p.79)

All over Europe, liberalism and nationalism were accompanied by a decline in educational freedom and the growth of a state monopoly in education. In this way, ‘great forces are at work which have changed the lives and thoughts of men more effectively than the arbitrary power of dictators or the violence of political revolutions’. (p.77)

Dawson warned that, ‘once the State has accepted full responsibility for the education of the whole youth of the nation, it is obliged to extend its control further and further into new fields: to the physical welfare of its pupils – to their feeding and medical care – to their amusements and the use of their spare time – and finally to their moral welfare and their psychological guidance.’ (p.78)

So strong, however, was the organic unity of Western culture, rooted in the marriage of Athens and Jerusalem, that even extreme forms of modern nationalism had been unable to create ‘any real cultural and spiritual autarky.’ (p.92) According to Dawson, ‘the history of Western culture has been the story of the progressive ‘civilisation’ of the barbaric energy of Western man and the progressive subordination of nature for human purpose under the twofold influence of Christian ethics and scientific reason.’ (p.94)

Using 'culture' in the broad sense of 'the whole pattern of human life and thought in a living society,' Dawson believed that, 'the educated person cannot play his full part in modern life unless he has ... a knowledge of our Christian roots and of the abiding Christian elements in Western culture.’ (p.149)

The culture of Christendom, Dawson argued, ought to be studied as an objective reality - not as propaganda or indoctrination: ‘what we need is not an encyclopaedic knowledge of all the products of Christian culture, but a study of the culture-processes itself from its spiritual and theological roots, through its organic historical growth to its cultural fruits.’ (p.254)

Each student must get a glimpse of ‘the intellectual and spiritual riches to which he is heir’. (p.150) And so there must be an initiation: ‘taken in its widest sense education is simply the process by which the new members of a community are initiated into its way of life and thought from the simplest elements of behaviour up to the highest tradition of spiritual wisdom.’1

‘Christian education is therefore an initiation into the Christian way of life and thought…nowhere else in the history of mankind can we see such a mighty stream of intellectual and moral effort directed through so many channels to a single end…and no one has any right to talk of the history of Western civilisation unless he has done his best to understand its aims and its methods.’

The spiritual vacuum in Western culture, he warned, is a danger to its existence: ‘a common bond of loyalty and the will to cooperate in essentials, in spite of all disagreements and divergencies of interest…is essential to the existence of a free society and consequently it is the key–point against which the totalitarian attack on Western Culture is directed.’2

‘The tactics of totalitarianism’, he said, ‘are to weld every difference of opinion and tradition and every conflict of economic interests into an absolute ideological opposition which disintegrates society into hostile factions bent on destroying one another,’ creating ‘an inferno of hatred and suspicions.’3

‘A complete change of spiritual orientation…can only be reached by a long and painful journey through the wastelands’ (p.217), leading to ‘membership of a real community, more real than that of nation or state and more universal than secular civilisation. It is a community that transcends time so that past and present coexist in a living reality.’ (p.201)

Unless footnoted, all quotations are from Dawson’s The Crisis of Western Education.

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2016/05/christian-education-initiation-christian-way-life.html

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2016/06/left-right-fallacy-timeless.html

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2016/06/left-right-fallacy-timeless.html

Your blog and accompanying youtube channel are excellent.

An important theme which begs to be expanded into a series of articles on how declining Christianity and spirituality are affecting Western culture.