Luther famously called Islam ‘the scourge of God’ — a corrective instrument for Christian civilisations turned degenerate. Developing this insight, E. Michael Jones says in Islam and Logos that

‘Islam always arrives on the scene when Christianity has failed’ because it’s ‘the sign that God has run out of patience with lukewarm Christians who do nothing to preserve the social and moral order from soul-destroying decadence.’ (Fidelity Press 2016, p.102)

If Islam’s appeal is growing today, as Andrew Tate’s conversion would suggest, it’s the latest example of this centuries-old phenomenon. Indeed, you can’t understand the crisis of masculinity in Christianity and the West at large without understanding Islam. As Chesterton warned in ‘The Fall of Chivalry,’ Islam’s lack of ‘self-correcting complexity’ by comparison with Christianity meant ‘it allowed of those simple and masculine but mostly rather dangerous appetites that show themselves in a chieftain or a lord.’

But the caricature version of Islam presented in Western education means it’s poorly understood. This article will explain what I admire about Islam, why I think it’s superior to secular liberalism and why I am nevertheless not a Muslim.

Muhammad and the message of Islam

Muhammad was born c.570 AD and adopted by his uncle at age 8 after losing his father, mother and grandfather. At age 25, he then married a 40-year-old widow, Khadija, and their marriage was monogamous until she died when he was 50. Only in the last years of his life did Muhammad take multiple wives, and it was for the purpose of unifying warring tribes — a fact neglected in cartoon versions of Islam.

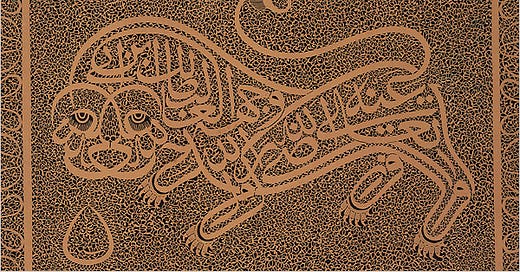

The defining event of his life was the Night of Power in 610 A.D., when Muhammad said an angel commanded him to preach. The Koran says the angel told Muhammad, ‘Proclaim in the name of your Lord who created! Created man from a clot of blood. Proclaim: Your Lord is the Most Generous, Who teaches by the pen; Teaches man what he knew not.’ (Koran 96:1-3).

Despite initially refusing the angel three times due to feeling unworthy, Muhammad then preached for the remaining 23 years of his life. The angel gave him one command: Iqra’—Recite! And al-qur’an (‘koran’) means simply ‘a recitation.’ The Koran is presented as God Himself speaking in the first person. Only in the recitation, Muslims believe, can the barakah (similar to ‘grace’) of the message be conveyed.

This is why it’s a common misconception to compare Muhammad to Christ. It would be more accurate to compare the Koran to Christ. In fact, the Koran is often called a ‘Sword of Discrimination’ because it cuts between good and evil, and Christ also came to bring ‘not peace but a sword’. As the Western convert Charles Le Gai Eaton explains in Islam and The Common Destiny of Man,

‘For Christians the Word was made flesh, whereas for Muslims it took earthly shape in the form of a book, and the recitation of the Quran in the ritual prayer fulfils the same function as the eucharist in Christianity.’ (State University of New Press Press, 1985, p.73)

Another misconception is that Islam can be called Mohammedanism. Christianity is properly named after Christ because He is God, but Islam is similar to Buddhism in being named after its doctrine, not its founder. Just as budh means ‘awakening,’ Islam means ‘peace’ or ‘surrender.’ Muslim means ‘one who submits,’ and Islam aims at ‘the peace that comes with surrender to God.’

This was the central idea of Islam, tawhid: the contemplation of the One God, the God Who is One. Alone among all world religions, only Christianity, Islam and Judaism get monotheism correct. Islam calls all three — Christians, Muslims, and Jews — ‘People of the Book’. As the first line of the Nicene Creed says, ‘We believe in One God.’ Indeed, the Catholic Church, in its Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions, ‘views with esteem the Muslims, who worship the one and only God, living and subsistent, merciful and omnipotent, the Creator of heaven and earth.’

No, this isn’t a trendy post-Vatican II position: Pius X’s Catechism, too, said Muslims rightly admit only ‘one true God’.

When he first preached Islam in Mecca, Muhammad met with great hostility because he said there weren’t many gods but only ‘the God,’ Allah. In the year 622, after suffering persecution, he was therefore invited to lead a new Islamic community in Yathrib (280 miles north of Mecca). He took 70 families with him, and Muslims date their calendar from this event. The city came to be called Medinat al-Nabi, the City of the Prophet — Medina.

The Confiscation of the Political

At Medina, the orphan Muhammad — husband, businessman, warrior — became a successful political leader. In this respect, Muhammad was more like Moses than he was like Christ. The Koran is the basis of the Sharia: the rules that govern Islamic society. God determines it directly, and there is no ordinary life.

For Islam, everything is religious: it encompasses legal administration and economic policy. Whereas Christianity makes a distinction — not, as most people think, a separation — between Church and State, Islam absorbs the State. Roger Scruton termed this ‘the confiscation of the political’.

Muhammad therefore managed all aspects of society. For example, Zakat, the third pillar of Islam, concerns almsgiving. It means ‘purification’: what’s left after the zakat has been purified. Comprising 2.5% of one’s income and total holdings, it cultivates sacrifice and ensures society is strengthened by its wealthiest members. According to the Koran, ‘with hardship cometh ease,’ and Muhammad said that 'Paradise is surrounded by things that you dislike'. Unlike the Christian tithe, which primarily supports Churches, the Zakat is socially direct because it has to be distributed back into the same community from which it came.

Islam emphasises orthopraxy (right practice) over orthodoxy (right belief) because it has no equivalent of the Catholic magisterium to determine orthodoxy. Even Jews and Christians living in Muslim lands also had to pay a special tax in lieu of the Zakat, forcing them to contribute to the general welfare of the community. But Sharia permitted toleration of People of the Book. When visited by Christians, for example, Muhammad allowed them to conduct their religious services in his mosque, Indeed, according to Islam, all religions that speak of the One God are Islamic. And all believers who testify and surrender are muslim — hence Abraham is called muslim.

The Koran says that in Heaven there is the Umm al-kitab, the Mother Book, that is the source of all revelations. And although it regards Muhammad as ‘The Seal of the Prophets,’ meaning the fullest and final one, Islam also regards Jesus and many other Biblical figures as genuine prophets. In fact, like Jews, Muslims trace their lineage back to Abraham: Muslims are descended from him via Ishmael whereas Jews are descended from him via Isaac. But they are both descendants of Shem — Noah’s son, whose line produced Abraham — and hence both Semites.

Islam especially reveres Jesus and Mary. According to Islam, only Adam and Christ had their souls created directly by God. And the Koran says Mary was surrounded by divine grace from her birth and affirms her perpetual virginity. Islam is very stern with the Jews for rejecting Mary. Whereas there is a parallel between Christ and the Koran, there is also one between Mary and Muhammad: just as Mary didn’t taint Christ with sin, Muhammad was a channel for the Word without tainting it.

Creation and Redemption

Towards the Trinity and the Incarnation, however, Muhammad felt great antipathy. For Muslims, shirk — the denial of tawhid, the Oneness of God — is the ultimate vice. Islam believes Christians sin by saying God is Three Divine Persons in One nature. But it believes this sin of Christians is lessened because, as Muhammad Asad says in The Message of the Quran (p. 160, note 97), it 'is not based on conscious intent, but rather flows from their “overstepping the bounds of truth” in their veneration of Jesus’. In other words, Islam says Christians have been so overwhelmed by their prophet Jesus that they have come to believe He is God.

For Islam, however, the Incarnation not only compromises the Oneness and absolute transcendence of God, but it’s also unnecessary. This is because there is no Original Sin. Man does not need redeeming. He simply needs reminding of what he has forgotten. For Islam, man isn’t fallen. ‘[God] created man in the best of stature’ (Koran, 95:4), and man has retained that stature. Whereas Christian original sin says man is weakened in will and intellect, the Islamic ghaflah means merely being prone to forgetfulness.

In Islam, then, man doesn’t need a miracle to save him. He just needs to be told what to do. Islamic soteriology is simply about knowledge. Muslims think Jesus was merely repeating the same message given to Adam but doing so less effectively than Muhammad did. The only miracle in Islam is Revelation itself: the Koran. Muhammad performed no miracles and also refused to perform them. By contrast, the entirety of Christianity rests on the Resurrection.

Significantly, in denying the Trinity, Islam believes that the purpose of creation was so that God could know Himself through His creatures, whereas the Christian God already knew Himself perfectly and created the angels and man to enjoy Him.

Logos and Will

In addition to denying relationally in God, Islam also denies rationality. Abu Hasan al-Ash’ari (873-935) said that God is ‘pure will, without or above reason.’ This is why Islam has traditionally been hostile to science. In fact, in Science and Creation, Stanley Jaki shows that only within Christendom nourished science: in Arabic, Babylonian, Chinese, Egyptian, Greek, Hindu, and Mayan cultures, it suffered a “stillbirth.”

The idea of physical laws, according to Islam, is blasphemy because it restricts Allah’s absolute autonomy. He might discontinue them at any time. For Islam, the universe is therefore deeply irrational. Indeed, like David Hume, al-Ghazali said there is no “natural” sequence of cause and effect. Because of this view, Islam couldn’t provide the necessary metaphysical foundations for science.

Accordingly, although it’s politically correct to talk about Islamic achievements in science, Lewis points out in What Went Wrong?, that Arabs inherited ‘the knowledge and skills of the ancient Middle East, of Greece and of Persia.’ (OUP, 2002, p.6) For example, Samuel H. Moffett points out in A History of Christianity in Asia, the ‘earliest scientific book in the language of Islam’ was a ‘treatise on medicine by a Syrian Christian priest in Alexandria, translated into Arabic by a Persian Jewish physician.’ (HarperSanFrancisco, 1992, Vol 1, p. 344)

By contrast, the Bible says, God ‘ordered all things by measure, number, weight’ (Wisdom 11:21). As the English philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead explained in Science and The Modern World, science developed in Europe because of the widespread ‘faith in the possibility of science … derivative from medieval theology.’ (Free Press, 1967, p.13.) For Christians, scientific investigation of nature could only reveal order because God had ordered it.

In his Regensburg speech, Pope Benedict criticised Islam’s relation to reason because it’s not docile to Logos. Allah’s will is arbitrary. Instead, the Christian view of God’s relation to reason entails that He could not in principle abolish the Ten Commandments. God is necessarily worthy of worship, for example, and it is against man’s rational nature to murder. These things cannot possibly be otherwise. God is the eternal law as divine reason, and man’s reason participates in that.

The Scourge of God

Allah differs from the Christian God, then, in representing the pure will to power. The Christian God cannot act contrary to His Eternal Law by permitting marriage between parent and child, for example. But Allah is will over rationality. This appeals to the liberal mind while Sharia law orthopraxy relieves the disorientation caused by secular liberal social chaos.

Another way Islam appeals to the liberal mind is that the absence of a magisterium makes it more similar to Protestantism than it is to Catholicism. Finally, as Aquinas pointed out, Muhammad ‘seduced the people by promises of carnal pleasure to which the concupiscence of the flesh goads us.' As it did in Muhammad’s time, this appeals to ‘carnal men’ in our time. Furthermore, it appeals to the liberal mind in its emphasis on man’s essential sinlessness and his salvation by knowledge.

But perhaps the greatest appeal of Islam is its simplicity. As Hillaire Belloc explains in The Great Heresies, what Muhammad ‘taught was in the main Catholic doctrine, oversimplified’. Indeed, Belloc says,

‘the very foundation of his teaching was that prime Catholic doctrine, the unity and omnipotence of God.’

‘The attributes of God he also took over in the main from Catholic doctrine: the personal nature, the all-goodness, the timelessness, the providence of God, His creative power as the origin of all things, and His sustenance of all things by His power alone.’

‘The world of good spirits and angels and of evil spirits in rebellion against God was a part of the teaching, with a chief evil spirit, such as Christendom had recognized.’

‘Mohammed preached with insistence that prime Catholic doctrine, on the human side -- the immortality of the soul and its responsibility for actions in this life, coupled with the consequent doctrine of punishment and reward after death.’

The strength of Islam, then, derives from its Catholic content. And that commands respect: heresies can persist for centuries because of the grain of truth they contain.

Naturally, Islam’s errors are all its own. For example, Aquinas was right to point out in Summa Contra Gentiles (Book 1, Chapter 16) that no ‘divine pronouncements on the part of preceding prophets offer [Muhammad] any witness’. Nor did Muhammad ‘bring forth any signs produced in a supernatural way, which alone fittingly gives witness to divine inspiration; for a visible action that can be only divine reveals an invisibly inspired teacher of truth.’

Islam also faces not only all the problems of Unitarianism (such as a God who needs creatures in order to be known and loved) but the added problems of a God who can act irrationally. But as Chesterton warned with grave understatement in The Illustrated London News (Nov. 15, 1913),

you will not find in the Koran ‘strong encouragements to the worship of idols’

nor will ‘the praises of polytheism…be loudly sung’

nor will ‘the character of Mohammed…be subjected to anything resembling hatred and derision’.

And you certainly won’t find ‘the great modern doctrine of the unimportance of religion’.

The scourge of God has taught these vital lessons in the past, and it’s time for the West to learn them again.

Thanks for this Will. Very interesting. It makes me chuckle when feminists decry Islam as bad for women. The Islamic prophet did so much to advance the dignity of women.

This was a brilliant and well researched essay and I learned a lot! I especially found it interesting how you revealed that the Koran and not Mohammad is most analogous to Christ. Really enjoyed the clear writing! I can tell you must have been a great teacher