In her article ‘The virtues of masculinity’, Mary Harrington ends with an important warning about how contemporary culture is demonising traditional male traits:

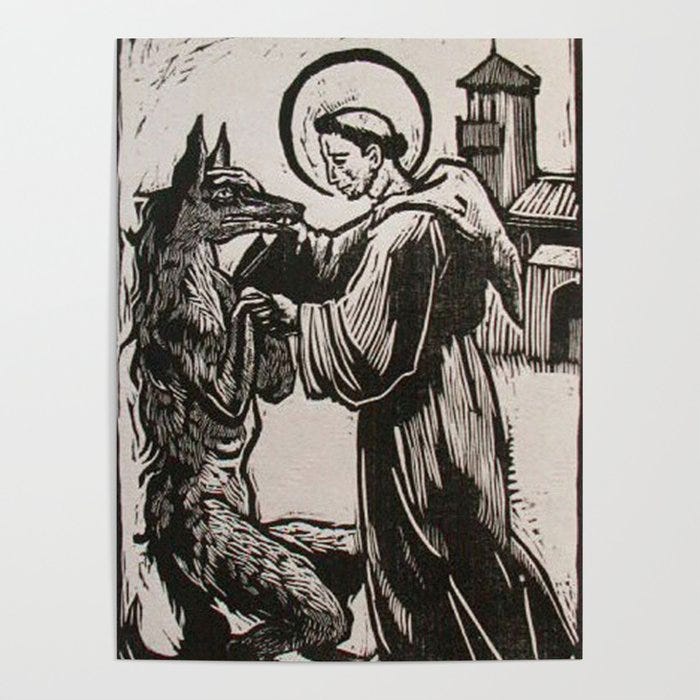

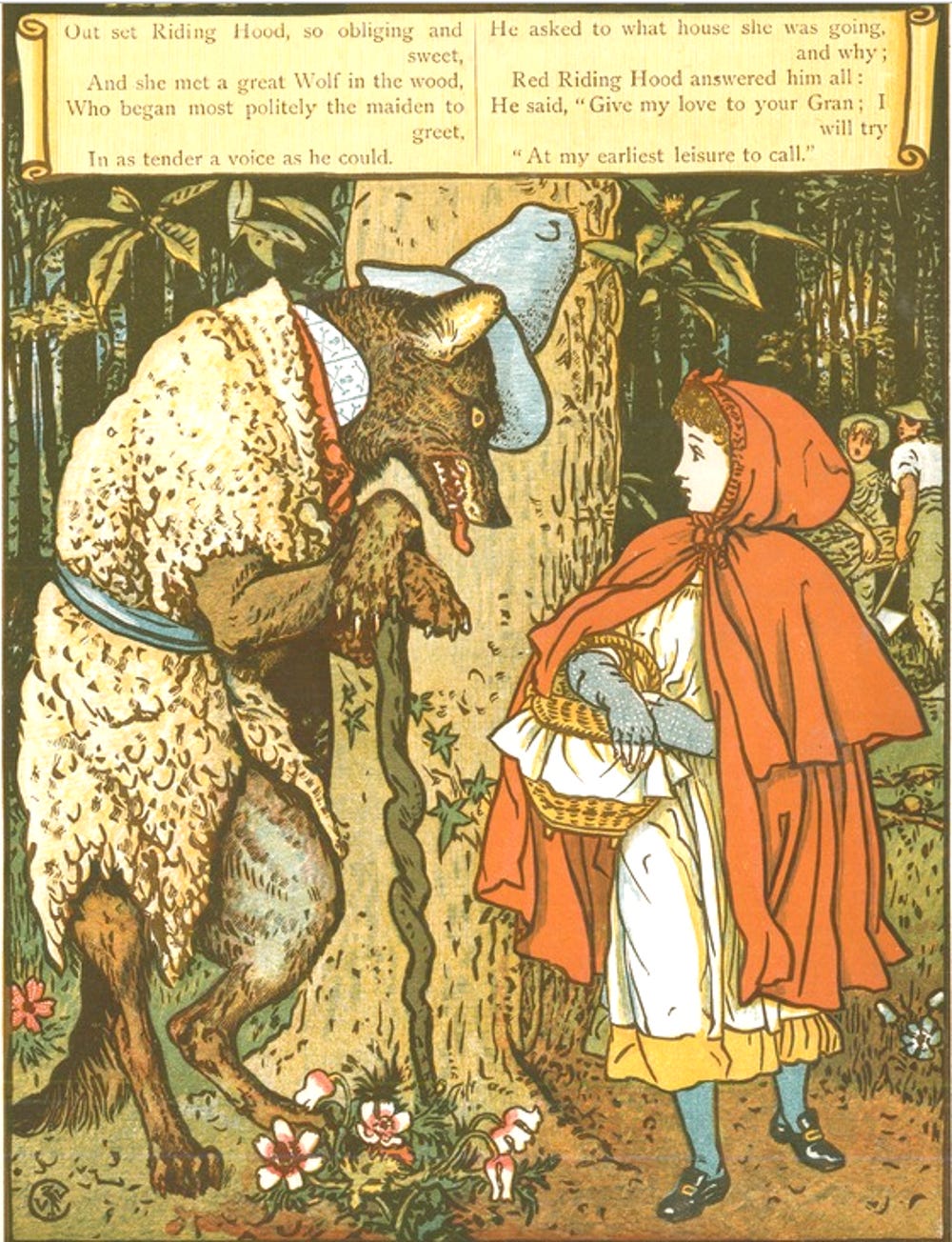

‘for men whose personalities tend toward aggression, protectiveness, competition and stoicism, what honourable roles are left? We’d be foolish to shrug our shoulders as such men lose hope of being valued as protectors, and start looking for glory as wolves.’

Either protector — or wolf. But is it really that simple? For both the Romans and the Egyptians, the wolf symbolised valour. The word, meaning ‘value, worth’, derives from Old French valor, valour "valor, moral worth, merit, courage, virtue" (12c.), from Late Latin valorem (nominative valor) "value, worth" (in Medieval Latin "strength, valor"), from stem of Latin valere "be strong, be worth”. And the Middle English word also had a sense of “worth or worthiness in respect of manly qualities”.

Sheep can’t protect. But the problem is that what makes the wolf able to also means he has great destructive potential. Fenris, the wolf of Norse myth who destroyed his iron chains and was eventually imprisoned in the bowels of the earth, breaks free with the twilight of the gods to devour the sun. Masculinity is like this.

Man is by nature a social animal, said Aristotle. He who lives alone must be either a beast or a god. Valour is ultimately about virtue — “moral strength, high character, goodness; manliness; valor, bravery, courage (in war); excellence, worth” — and this derives from vir, “man”. If glory is the pride, boasting and vanity of the lone wolf, virtue is about flourishing in the pack.

Our common humanity links us to our fellow men so closely, in fact, that society reflects our individual failings or virtues. Ultimately, there is no such thing as a purely private act. “Why do you care what goes on in other people’s bedrooms?” Because someone sitting in his bedroom doing DMT every night because he’s listened to too much Joe Rogan is damaging the common good, depriving society of the proper use of his life.

The strength of the virtuous man — the whole, well-balanced and fully human man — comes from living with his specifically human powers of mind and of will developed to the peak of their possible perfection. To the extent that the sense appetites (food and sex) are under the control of intellect and will, it also controls them.

Virtue, then, is defined by St. Thomas as a good quality or habit of the rational powers which renders them capable of acting rightly and which cannot be used badly. Why does he call it a quality or habit? Because it is a kind of increase or growth within the power, a super-excellence or perfection of the power. These habits fulfill human nature.

By contrast, instinctive responses or physical mannerisms are not habits in this sense. And whereas virtue perfects, vice deforms. The alcoholic, the crack addict and the masturbating MAP all suffer a lack of a good that should be there. In them human nature is not fulfilled. The consequences of his, remember, are not purely private. The alcoholic, for example, might neglect his family.

Since the virtues perfect either the knowing (intellect) or desiring (will) side of man’s nature, they fall into two classes: intellectual and moral. This article is mainly about the moral virtues, but it’s worth stressing here that vice, as the contrary of virtue, means a bad disposition opposed not just to doing good but to attaining truth.

The cardinal virtues get their name because they are the hinge (Latin cardo) on which our lives turn:

Prudence is the habitual right thinking about things that have to be done in the moral order.

Justice is the virtue which perfects the will, enabling it to order our acts rightly in relation to our fellow man.

Temperance is the virtue which strengthens and orders the passions of the concupiscible appetite (feelings of pain and pleasure).

Fortitude is the virtue which helps us to act rightly and easily in the realm of the irascible appetite (instincts such as the fear of death).

Our actions, then, must be done consciously and for the right reason (prudence). They must be rightly ordered with regard to society (justice). We must persist in the face of obstacles (fortitude). And our choices must be moderated (temperance). Lacking any one of these affects all the others. A just judge will make a poor judgement under moral pressure if he lacks fortitude. The alcoholic’s intemperance will affect his prudence.

Schools often like to claim they teach virtue. But Aristotle said that you cannot teach virtue to the young: because they are inexperienced, they haven’t been able to form the virtue of prudence. Instead, the young simply have to be forced to behave properly until they understand that is how they should behave.

And many people can give great advice but can’t carry it out. What’s the point of prudence - deciding how to act rightly - if you don’t actually act on it? The senses blindly drive us toward pleasure and away from pain. So this is where temperance and fortitude bring them under the control of reason.

The desires for food and sex are hardest to control because they are survival instincts — food for the individual and sex for the species. Gluttony harms the body. Similarly, sexual promiscuity - sex outside marriage - endangers the welfare of offspring. And Puritanical distrust of food and sex is also bad because it goes to the other extreme.

Although a lack of temperance is clearest in food and sex, it is apparent in other aspects of contemporary culture. Temperance is about valuing things properly, not exploiting and perverting them with a disordered love. Your dog is just a dog. Your car is just a car. Your career is just a career.

Even with all the other virtues in order, without fortitude we won’t endure physical pains and face great danger reasonably. More than any of the other virtues, fortitude illustrates stability and constancy. Fear, for example, as Aristotle noted, is always a condition of courage: a man acting out of uncontrolled anger is "pugnacious but not brave,” animalistic rather than human.

In The Case for Patriarchy, Timothy Gordon writes that, ‘post-feminism, fathers will be heard referring the practice of all the other virtues back to exercises in courage. Are we brave enough to be just? Are we brave enough to be temperate?’ Derived from fortitudo (‘manliness’), from fortis (‘strength’), fortitude confers vigour.

Whereas prudence, fortitude, and temperance — the individual virtues — mainly perfect the person in his private activities, justice — the social virtue — concerns perfecting his actions in relation to others. And in Moral Theology (1930), Callan and McHugh outline what the threat to society today demands from men as the protectors of the pack:

‘The first act of fortitude, namely, attack, requires greatness of soul (which makes one love the best things and despise all that is opposed to them) and greatness of deed (which makes one perform generously what was nobly willed).

The second act of fortitude, namely, endurance, requires patience (that the soul be no thrown into dejection by difficulties) and steadfastness (that the soul be not turned aside from its purpose or wearied by long-continued opposition.

Since the life of man is a warfare (Job, vii. 1), fortitude is always required to defend the fortresses of heart, home and heritage.

Topic hijack: referencing discussion from YTube (https://knowlandknows.substack.com/p/the-cardinal-virtues/comments?s=r) in more open SubStack forum...

>> There's a very interesting website called "<redacted> Contributions" which details how much <redacted> have contributed to the shaping of Western society. Feminism, hardcore porn, relaxing immigration policies, and many more progressive changes have been driven by <redacted>. People can debate whether those changes were for good or ill, but it's undeniable how much <redacted> have contributed to driving those changes.

> Knowland Knows

> Nobody was forced to accept any of them.

Are you saying that men in the West should be more cognizant of policies and positions that aren't actually in their own best interest? If so, perhaps it'd be good for the few who do recognize associated pitfalls to help educate their brethren. E.g., they could warn about the negative consequences and point out how to identify when an argument is couched in terms of Western values but actually intended for the benefit one particular minority group. It might also be good for men of the West to broaden their understanding of history--to understand that the subversion of a people doesn't always have to be militaristic in nature. Those in the West could be encouraged, to actively resist their cultural, financial and political overthrow. They could be deprogrammed from accepting the outcomes of prior campaigns against them as eternally binding and legitimate. Why should the men of today accept servitude to a chain (extending back at least to the mid-1700s) of financial/inflationary schemes against them if we're capable of building a society independent of such dynastic fraud? Should we not cast the self-sanctificating globalist bankers off and re-kindle the will to live like our ancestors as sovereign nations on the world stage?

> Nobody was forced to accept any of them.

The first step in rejecting such 'contributions' is to learn to recognize positions that are anti-independence / anti-national. Recognition is significantly helped when the true beneficiaries of such positions are 'named'.