Sometimes you read sentences you never forget. In his introduction to Pascal’s Pensées, T. S. Eliot remarks,

‘The majority of mankind is lazy-minded, incurious, absorbed in vanities, and tepid in emotion, and is therefore incapable of either much doubt or much faith; and when the ordinary man calls himself a sceptic or an unbeliever, that is ordinarily a simple pose, cloaking a disinclination to think anything out to a conclusion.’

I loved T. S. Eliot’s poetry - ‘I can connect nothing with nothing,’ the heart of The Waste Land, resonates perhaps even more now, in 2022, than it did when first published in 1922 - so to read Eliot on Pascal, who haunted another of my favourite writers, Nietzsche, was to eavesdrop on a conversation across the ages. At its best, that’s what reading is.

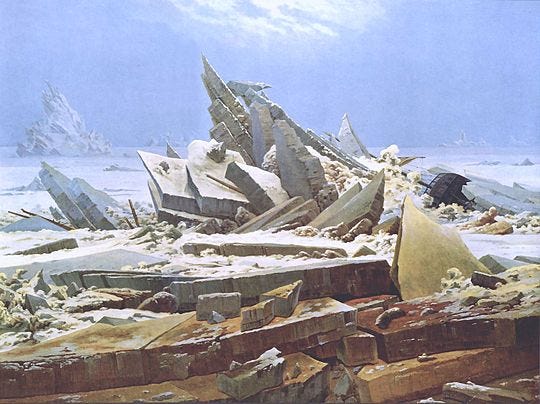

‘A disinclination to think anything out to a conclusion’ - reading this as a superficial adolescent atheist, I felt called out. Had I thought it out to a conclusion? No. But this is what great writers are for: ice-axes, Kafka said, to break the frozen sea inside us. And that ice has never been thicker because liberal pluralism is often taken as an excuse for not seeking truth. If whatever I want is ‘true for me’, why seek? Why not just state? In fact, ultimately, as Nietzsche asked, ‘why truth?’

As Pascal warned, ‘those who do not love truth excuse themselves on the grounds that it is disputed and that very many people deny it.’ In the great conversation of Western culture, some voices are especially powerful. Pascal’s is one, and his work is even more relevant to our time than it was to his own.

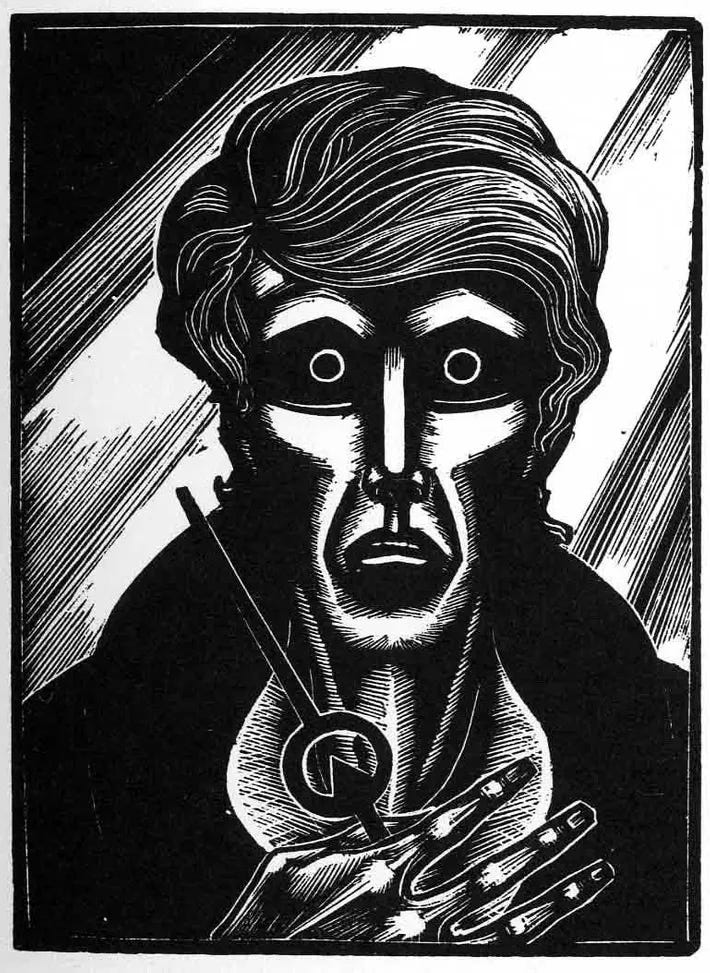

Chateaubriand called him a ‘terrifying genius.’ Partly this is due to his being one of the greatest physicists and mathematicians ever. Aged only 16, he discovered the theorem of the Mystic Hexagon (known as Pascal’s Theorem), and his further work in maths was the foundation of the science of statistics. But he also gave the first outline of a system of hydrostatics in the history of science, and his other efforts in physics led to the measurement of altitude from barometric pressure. Besides that, he organised the earliest system of hansom cabs in Paris, invented the wrist watch and designed the first mechanical calculator.

This ‘terrifying genius’ also had profound insight into human psychology. In 1654, Pascal, then aged 31, was driving across Neuilly bridge with some friends when their horses frighted, jumping into the Seine. The carriage teetered on the parapet. Finally, Pascal and company were rescued, but he was never the same afterwards. Kierkegaard wrote that such experiences are ‘the infinite intensely concentrated in a single pressure and in a single moment of time’ and propel a man into ‘the service of the Absolute’.

In other words, man’s extremity is God’s opportunity. Later that year, on 23 November, he underwent what he described as his 'night of fire’ — a conversion experience. Increasingly withdrawing from his earlier life of high society and science, he wrote his Pensées or ‘thoughts’, a defence of the Christian religion.

Despite being unfinished, it is said to have disturbed even Voltaire with its power and profundity. Like Nietzsche, Voltaire couldn’t shake Pascal off. Here again, T. S. Eliot wrote memorably:

‘Voltaire has presented, better than any one since, what is the unbelieving point of view; and in the end we must all choose for ourselves between one point of view and another.’

Either we are immortal or not. And this is not, Pascal stresses, merely ‘a philosophical question’; rather, ‘everything is at stake’ because ‘it is a question of ourselves, and our all’, and on it ‘all our conduct depends.’

Nobody lives as an agnostic. Superficial, sophisticated liberals who claim to live without metaphysical convictions actually constantly manifest them in their actions. Pascal is more akin to great creative writers in this respect than to the formal logic of contemporary analytic philosophy. ‘It is impossible to be a man and not bow down to something,’ wrote Dostoevsky. ‘There could not be such a man. Nor could such a man bear the weight of himself.’ Similarly, for Pascal, the alternative to theism is actually idolatry.

Although a great scientist, mathematician and logician, Pascal did not focus on the rational proofs of classical deism:

‘It is a remarkable fact that no canonical [Biblical] author has ever used nature to prove God. They all try to make people believe in him. David, Solomon, etc., never said: “There is no such thing as a vacuum, therefore God exists.” They must have been cleverer than the cleverest of their successors, all of whom have used proofs from nature.’

Pascal’s point is not that the arguments from nature are logically weak. The point is they’re psychologically weak. In a characteristically wise remark, he explains that

‘the metaphysical proofs for the existence of God are so remote from human reasoning and so involved that they make little impact, and, even if they did help some people, it would be only for the moment during which they watched the demonstration, because an hour later they would be afraid they had made a mistake. What they gained through curiosity they lost through pride.’

Pascal sees the uselessness of what Newman was later to term ‘paper logic’. Instead, he asks us to consider, for example, whether the Apostles were deceivers:

‘The human heart is singularly susceptible to fickleness, to change, to promises, to bribery. One of them had only to deny his story under these inducements, or still more because of possible imprisonment, torture and death, and they would all have been lost. Follow that out.’

‘Follow that out’ - that is, think it out to a conclusion. Do men die for what they know to be a lie? The human heart is Pascal’s target. He believes the great maxim of Classical humanism, ‘Know thyself,’ is impossible. Man can never understand himself as man. To be human is to be hopelessly mysterious — even to ourselves.

The philosopher Jerry Fodor famously remarked, summarising the state of modern philosophy of mind and neuroscience, that ‘nobody has the slightest idea how anything material could be conscious. Nobody even knows what it would be like to have the slightest idea about how anything material could be conscious.’ Augustine would have approved: how ‘bodies and spirits are bound together and become animals, is thoroughly marvellous, and beyond the comprehension of man, though this it is which is man.’ (City of God, Bk 21, Ch 10.)

As Pascal sees it, there are three main dangers: the pedestal of pride, the pit of despair, and the mediocre middle. Man truly fits in none of these and must be kept continually restless. Thus Pascal wrote,

‘if he praises himself, I humble him. If he humbles himself, I praise him. And I keep on contradicting him until he comprehends that he is a monster that is incomprehensible’.

Such is man’s nature that ‘some people’, Pascal remarks, ‘have thought we had two souls’ because ‘a simple being seemed to them incapable of such great and sudden variations, from boundless presumption to appalling dejection’ - the pedestal and the pit.

Etymologically, ‘monster’ derives from the Latin monstrum, ‘divine omen, portent, sign; abnormal shape; monstrosity’, which is a derivative of monere ‘to remind, bring to (one's) recollection’. And human nature, as a sign of man’s divinity, is for Pascal a reminder that ‘man is neither angel nor beast, and it is unfortunately the case that anyone trying to act the angel acts the beast’. Platonism, Gnosticism, New Age humanism: these angelic heresies all ignore the animal in man. ‘No bloodless myth will hold’, as Geoffrey Hill put it in his poem ‘Genesis’. Marxism, Darwinism, metaphysical naturalism: these animalist heresies all ignore the angel in man.

Chesterton, describing St. Thomas’s philosophy of man, said that ‘man is not like a balloon, floating free in the sky, nor like a mole, burrowing in the earth, but like a tree, with its roots firmly planted in the earth and its branches reaching up into the heavens’. Richly resonant in the world’s spiritual traditions (in Norse myth, Yggdrasil, the world tree, connects all the realms), the tree corresponds to the Cross of Redemption in Christianity , and the Cross is often depicted as the Tree of Life.

Hence Pascal’s famous image of man as the ‘thinking reed’:

Man is merely a reed, the weakest thing in nature, but he is a thinking reed. There is no need for the whole universe to take up arms in order to crush him: a trace of vapour or a drop of water is enough to kill him. But even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his killer, since he knows that he is dying whereas the universe knows nothing of its advantage over him.

Asked by a media interviewer during WW2 what he would do if he saw a German bomb falling on him, C.S. Lewis replied that he would stick his tongue out at it and say, ‘Pooh! You’re only a bomb. I’m an immortal soul.’

Man’s wretchedness, Pascal argues, is in fact the best proof of his greatness. ‘It is the wretchedness of a great lord, the wretchedness of a dispossessed king.’ Only the very great can be truly wretched. As the medieval theologians said, ‘the corruption of the best becomes the worst’ (corruptio optimi pessima est). The greatest criminals, for example, are masterminds. The ‘criminal strain in Moriarty’s blood,’ Conan Doyle writes in ‘The Final Problem’, ‘instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his extraordinary mental powers.’

With man’s capacity for rational thought, unique among animals, comes the capacity for deception. To be able to grasp the truth is to be able to lie. And man, says Pascal, is wilfully ignorant. Indeed, we hate the truth about ourselves. It hurts. ‘Men despise religion. They hate it and are afraid it may be true.’ The proofs of it, says Pascal, are ‘before their eyes, but they refuse to look.’

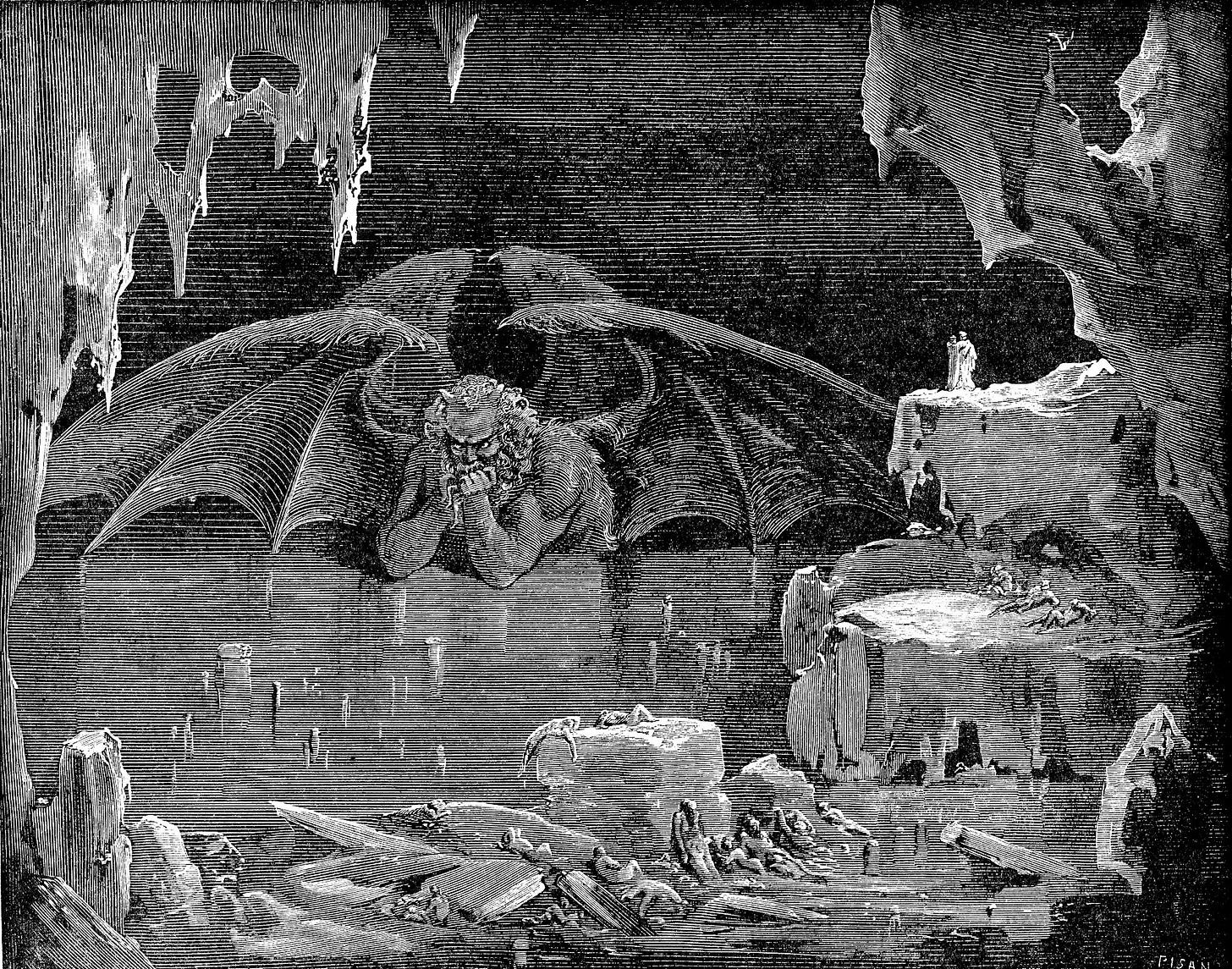

God hides, Pascal argues, because He ‘wishes to move the will rather than the mind. Perfect clarity would help the mind and harm the will. Humble their pride.’ This concept of the Hidden God - borrowed from Isaiah XLV 15, ‘Verily thou art a God that hidest thyself’ - is fundamental to Pascal’s thought. ‘There is enough light for those who desire only to see, and enough darkness for those of a contrary disposition.’ The damned are deprived only of what they do not desire:

‘Truth is so obscured nowadays and lies [are] so well established that unless we love the truth we shall never recognise it.’

What fallen man desires, Pascal argues, is diversion: we possess ‘a secret instinct’ for it. Men ‘think they genuinely want rest when all they really want is activity,’ and ‘the sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.’ Pascal says we seek constant diversion because ‘we are incapable of not desiring truth and happiness and incapable of either certainty or happiness.’ Ultimately, ‘without diversion there is no joy; with diversion there is no sadness.’

Since God is truth, all turning away from the truth, as Peter Geech argues in Truth and God, is turning away from God. Etymologically, the German Sünde ‘sin, transgression, trespass, offense’ and the English sunder, ‘to separate’, are linked. Sin, separation from God and self-deception go together. ‘We are nothing but lies, duplicity, contradiction, and we hide and disguise ourselves from ourselves.’

Pascal doesn’t seek a rational explanation of sin. That would be to succumb to the pride of philosophers. Reason’s last step, he says, is that there is an infinite number of things beyond it. It is ‘merely feeble’ if it does not recognise that. He is content to observe ‘this is not the home of truth; it wanders unrecognised among men’.

Not only unrecognised, in fact, but unwelcome: the eminent cosmologist Andrei Linde noted, for example, ‘the nonstationary character of the Big Bang theory [based on the] Friedmann cosmological models seemed very unpleasant to many scientists in the 1950s.’ They didn’t want it to be true.

Similarly, Fodor said he was a materialist regarding the mind because he found the alternatives unpleasant. And to avoid a theistic conclusion to the argument from cosmic fine-tuning, the materialist - having previously demanded empirical proof of God - will believe in an empirically unobservable infinite multiverse. He will even deny his rationality, claiming he is a mere machine.

It is ‘the wisest men…who imagination is best entitled to persuade,’ Pascal wisely remarks when noting that reason is often overpowered by imagination. He gives the memorable example of ‘the greatest philosopher in the world on a plank that is wider than it need be; and there is a precipice beneath him. Although his reason may convince him that he is safe, his imagination will get the better of him.’ (44)

The imagination, for Pascal, is a ‘proud power’ - the handmaiden of pride. Striving to be our own gods, we are forced to privately imagine we are perfect. And then we try ‘to lead an imaginary life in the minds of others’. One wonders what Pascal would have made of Instagram. He certainly wouldn’t have been surprised. This is because what we desire most is the esteem of others - “the most indelible quality in the human heart” - and since in reality we are too limited, only the imagination can satisfy this.

Pascal asks,

“Who dispenses reputation? Who makes us respect and revere persons, works, laws, the great? Who but the faculty of imagination? All the riches of the earth are inadequate without its approval”.

A magistrate’s robes, Pascal says, do not intrinsically manifest wisdom. Nor does bowing to one’s superiors intrinsically manifest respect. In fact, the commoner does not bow because the nobleman is superior; rather, the nobleman is superior merely because the commoner bows.

Indeed, all ‘the bonds securing respect for a particular person are bonds of imagination,’ Pascal argues: society works best when subordinates imagine their superiors are deserving of their power. Pascal read Montaigne’s account of how native Brazilians visiting Charles IX’s France ‘thought it very strange that so many grown men, bearded, strong, and armed, who were around the king . . . should submit to obey a child, and that one of them was not chosen to command instead.’

A king is actually Pascal’s paradigmatic example of someone who diverts himself from realising his own unhappiness: hunting, court intrigue and even war are all, Pascal says, ultimately diversions. Indeed, ‘we prefer the hunt to the kill.’ And this insight is particularly important for our own time. Politics on this view is like gambling or playing cards - a way to avoid boredom and reject God. It, too, can become an idol.

Semi-scripted reality TV shows increasingly dominate modern entertainment, but Pascal saw politics as a similarly distracting game. Political activity turns us away from uncomfortable truths about ourselves and our society. Progress means keeping your eyes on an imaginary future, forgetting human nature - with all its flaws and failings - is still going to be in it.

The Fall, for Pascal, is prior to any political arrangement. Because human beings bring their aversion to truth and their disordered love with them when they enter society, these are merely manifested in politics. In fact, it ramifies their effects. ‘All men naturally hate each other,’ warns Pascal.

‘We have established and developed out of concupiscence admirable rules of polity, ethics and justice, but at root, the evil root of man, this figmentum malum is only concealed; it is not pulled up.’

Our darkened intellects and disordered wills doom all dreams of a society founded according to just the right system, by just the right people, in the just right way. The fallen reality of human nature is unavoidable and politically ineradicable. That is what being based actually means. For Pascal, the founding myth of the American republic, for example, is a delusion.

But although Pascal sees politics as necessarily tragic because of the inevitable reality of sin, he affirms, contrary to Hobbes, for example, that true justice exists and that we have a dim grasp of it. Even for fallen man, moral progress is possible politically. Since disordered political systems are perpetuated through vice, however, they can only be combated through counter-institutions focused on truth. But Pascal is aware that, insofar as they comprise fallen men, all institutions are imperfect - even the Church because it is a mixture of the divine and the human. And Pascal often opposed the Church of his day.

Pascal’s doctrine of the three orders, T. S. Eliot stressed, ‘offers much about which the modern world would do well to think.’ For Pascal, the order of nature (strength, brute force, wordly power), the order of mind (intellectual and imaginative power) and the order of charity (love of one’s neighbour) are discontinuous. The higher is not implicit in the lower. You can’t get charity from mind any more than you can increase a line’s breadth by increasing its length. Man can’t raise himself up.

Because ‘they wished to humble, and not to teach’, Pascal observes, ‘Jesus Christ and St Paul possess the order of charity, not of the mind’. And towards the end of his life, Pascal belittled the importance of scientific research - the order of mind. He gave away his library along with his servants, silverware and horses. Only the Bible and St Augustine remained.

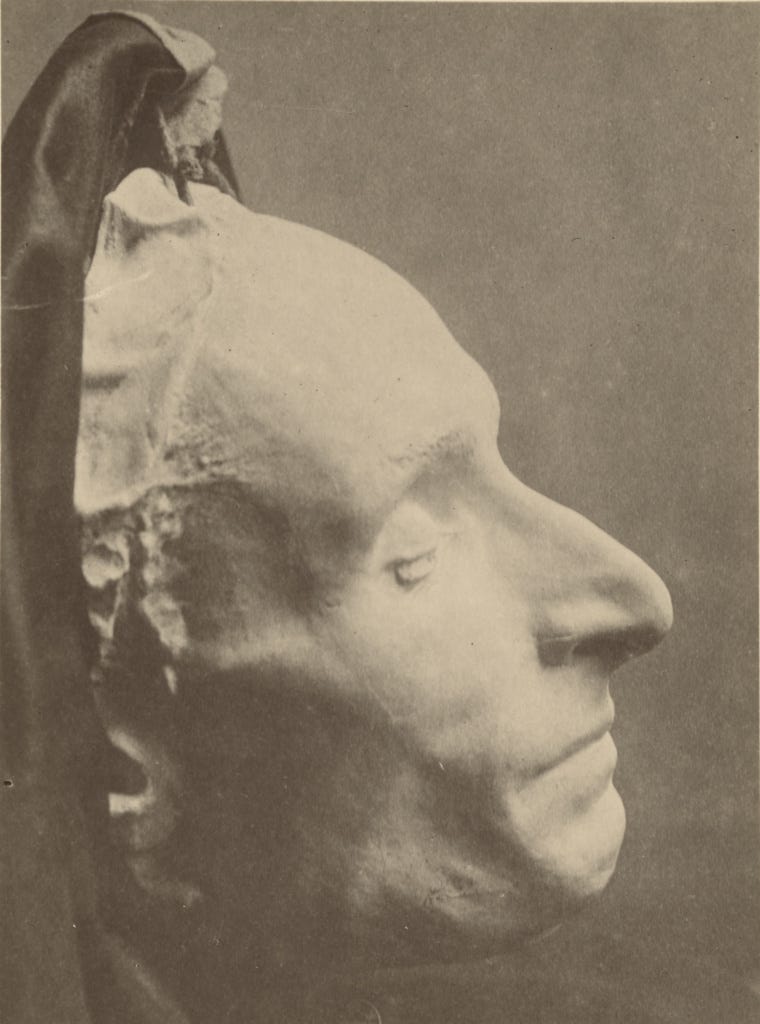

Suffering from an unnerving vertigo, believing a gaping gulf to be beside his chair, he always had another chair beside it to protect him. Perhaps the memory of the bridge haunted him.

By the end, the great mathematician, physicist and matchless stylist of French prose could be found giving street urchins reading lessons. Perhaps he taught them some writing as well, including a lesson he added to the end of one of his own letters that, like this article, had failed it: ‘I have only made this one longer because I have not had the time to make it shorter.’

The best thing you have written

Wonderful.