Love and Heroism in The Last Unicorn

'The true secret of being a hero lies in knowing the order of things.'

As the male rite of passage continues to dwindle in contemporary culture, the desire for it deepens. Starved of nourishing food for their hearts and minds, where can young boys turn? Many look to video games — often variations on the quest or journey archetype.

But fairy tale and fantasy literature offer an imaginative feast. Over half the Grimm's fairy tales, for example, feature boy heroes struggling towards manhood. And Peter Beagle’s novel The Last Unicorn, mostly encountered in the form of the cult 1980s animated film, also explores this in the character of Prince Lír.

Its quest narrative places it firmly within the medieval romance tradition, and Beagle’s allusions situate the novel in the world of mythology. The heroine of the title is named ‘Amalthea’ after Zeus’s nurse, while Prince Lír is named after the Irish sea-god. Minor characters, too, reinforce this mythic dimension: the witch Mommy Fortuna, for example, adopts the persona Elli, Old Age, whom Thor wrestled in Norse myth, and among the beasts in her Midnight Carnival are Cerberus and the Midgard Serpent.

But the Amalthea-Lír pairing is fundamental because it presents the masculine-feminine symbiosis. In Greek myth, Amalthea’s horn - she is represented either as the goat that fostered Zeus or the nymph that used a goat’s horn to feed him - was regarded as the symbol of inexhaustible fertility and plenty. And the Irish sea-god, Lír, has impenetrable armour, an invincible sword and protects sailors and provides crops. We first meet the unicorn deep in her home in the forest, Mother Earth, whereas Lír lives in a castle by the sea, traditionally masculine in mythology (e.g., Neptune, Triton).

Although we know nothing of Amalthea’s mother, Lír’s adoptive father - King Haggard, who knows neither ‘fear…nor rest’ - hates poetry and is incapable of love. The Red Bull serves him, and in attempting to find happiness Haggard makes it round up all the world’s unicorns (the only things that give him joy) into the sea at the foot of his castle.

When Amalthea, seeking to save the trapped unicorns, arrives at the castle disguised as a young lady, Lír falls in love with her, and Haggard hears him singing:

‘What business had he to be singing?…He was singing here, and not of battle and gallantry either, but of love. Where is she? I knew he was singing of love before I ever heard him, for the very stones shuddered as they do when the Bull moves in the earth.’

Haggard himself is loveless. ‘I always knew that nothing was worth the investment of my heart, because nothing lasts, and I was right, and so I was always old,’ he laments. Ultimately, this story is about the challenge and cost of love: where can we find the courage to commit to it in the face of mortality and mutability? Where Haggard fails, Lír succeeds.

Whereas Tolkien often used songs to advance his narrative, Beadle uses them as interruptions for philosophical emphasis. Mommy Fortuna, whose Latin name recalls Boethius’s Fortuna, sings one song in particular that haunts the book:

Here is there, and high is low;

All may be undone.

What is true, no two men know -

What is gone is gone.

This is the nihilism that gnaws at Haggard’s heart. The rug of reality, he fears, can be pulled from under our feet at any time.

He believes nothing is ‘worth the investment of… [his] heart, because nothing lasts.’ When he adopted Lír as a baby, ‘picking him up where someone else had set him down’ because he ‘had never been happy and never had a son’, he found ‘it was pleasant enough at first, but it died quickly. All things die when I pick them up.’

But if Haggard is unable to love because he fears death too much, seeing what T. S. Eliot called ‘the skull beneath the skin’, the immortal Amalthea is tragic because she faces ‘a story with no ending, happy or sad. She can never belong to anything mortal enough to want her.’ Unlike Haggard, however, she takes joy in mortality:

‘It was always spring in her forest, because she lived there…keeping watch over the animals…generation after generation…they hunted and loved and had children and died, and as the unicorn did none of these things, she never grew tired of watching them.’

Caught between these two extremes is Lír. According to Chesterton, ‘the inevitable result of love…is incarnation; and the inevitable result of incarnation…is crucifixion’. Haggard is hollow because he fears the crucifixion, whereas Amalthea, being immortal, lacks incarnation. But Lír both loves Amalthea and suffers the sting of mortality.

Faced with the option of leaving the unicorn in the form of Lady Amalthea to escape a battle with the Red Bull, Lír grows from boy to man. Amalthea begs him to let the magician leave her in human form:

“Everything dies,” she said, still to Prince Lír. “It is good that everything dies. I want to die when you die. Do not let him enchant me, do not let him make me immortal. I am no unicorn, no magical creature. I am human, and I love you.”

Love means incarnation. The magician agrees: ‘let the quest end. Is the world any the worse for losing the unicorns, and would it be any better if they were running free again? One good woman more in the world is worth every single unicorn gone.’ An appealing ending beckons: ‘Marry the prince and live happily ever after.’ Hearing this, Lady Amalthea says, ‘That is my wish’.

But Lír says, ‘No.’

The word escaped him as suddenly as a sneeze, emerging in a questioning squeak—the voice of a silly young man mortally embarrassed by a rich and terrible gift. “No,” he repeated, and this time the word tolled in another voice, a king’s voice: not Haggard, but a king whose grief was not for what he did not have, but for what he could not give.

What explains this transition from ‘silly young man’ to ‘king’?

“My lady,” he said, “I am a hero. It is a trade, no more, like weaving or brewing, and like them it has its own tricks and knacks and small arts…But the true secret of being a hero lies in knowing the order of things.”

He realises that ‘quests may not simply be abandoned’. When the magician asks ‘why not? Who says so?’, Lír ‘sadly’ replies, ‘Heroes…Heroes know that some things are better than others.’ As an agent of order against chaos, the hero subordinates his selfish desires. Love is not a subjective feeling; it is actively willing the objective good of the beloved.

He explains to Lady Amalthea, ‘I never looked at you without seeing the sweetness of the way the world goes together, or without sorrow for its spoiling. I became a hero to serve you, and all that is like you.’ Just as Andromeda chained to the rock calls forth the hero in Perseus, so Amalthea calls forth the hero in Lír.

In a nice touch characteristic of the wry comedy of the story, Lír adds that becoming a hero was necessary even for merely ‘starting a conversation’, capturing how the feminine overwhelmingly motivates the masculine.

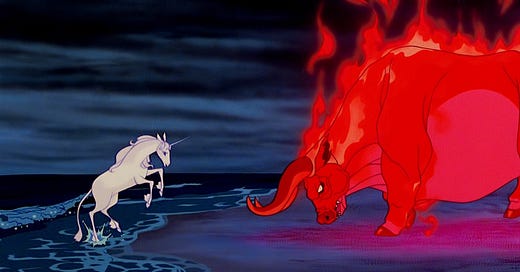

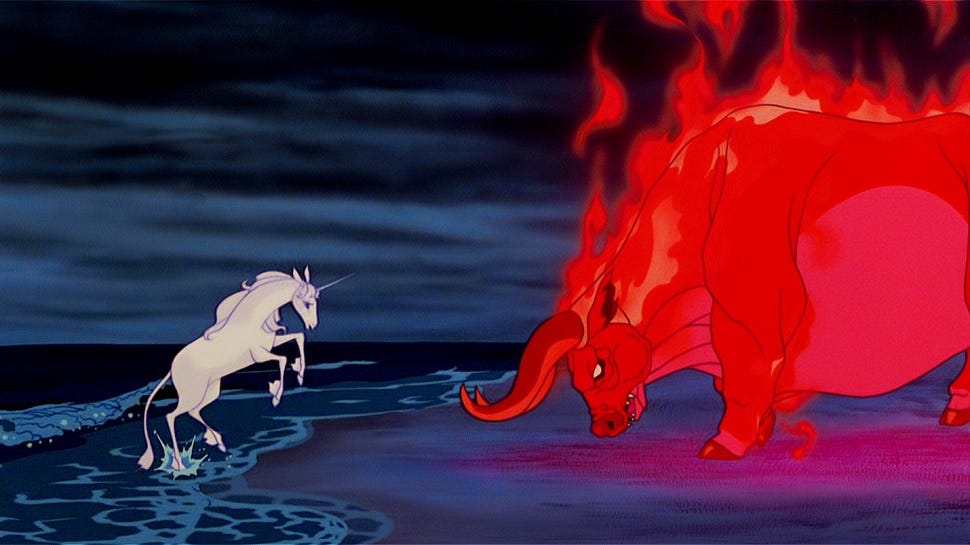

And so Amalthea is transformed back into unicorn form. But when the Red Bull attacks her, Lír begs the magician to help her. He can’t. “Then what is magic for?” Prince Lír asks. “What use is wizardry if it cannot save a unicorn” Without turning to look at him, the magician tells Lír, “That’s what heroes are for.” And so, unable to see Amalthea because the Red Bull - ‘blind and patient as the sea’ - is dwarfing her, Lír gives a ‘soft grunt of understanding’.

Duty calls. “Yes, of course,” he said. “That is exactly what heroes are for. Wizards make no difference, so they say that nothing does, but heroes are meant to die for unicorns.” Taking the sacrificial step, he stands ‘between her body and the Bull, weaponless, but with his hands up as though they still held a sword and shield. Once more in that endless night, the prince said, “No.”’

Like Hector stepping out to face Achilles, he never had chance. The Red Bull overpowered even Amalthea in their first encounter, despite her horn having not only healed kings but slain dragons: ‘He was too strong…too strong. There was no end to his strength, and no beginning.’ Lír disappeared ‘like a feather in a flame’.

What is gone is gone.

But the light touch of his love emboldens Amalthea’s heart. Seeing him die in her defence, she gives ‘an ugly, squawking wail of sorrow and loss and rage, such as no immortal creature ever gave.’ Like a vampire in sunlight, Haggard shrinks back, covering his eyes. ‘Lowing doubtfully,’ even the Red Bull hesitates. The castle quakes.

This moment touches the core of the story. Although the unicorns trapped in the sea can leave at any time, their fear of the Red Bull imprisons them. He ‘conquers, but he never fights.’ And just as the unicorns are afraid to fight back, Haggard is afraid to love. The Red Bull conquers by cowing the spirit.

Fighting him, ‘she might have been stabbing at a shadow, or at a memory.’ In The Lord of The Rings, Aragorn describes the Balrog as ‘both a shadow and a flame, strong and terrible,’ and there are Egyptian paintings of a black bull bearing the corpse of Osiris on its back. She knows she can ‘never destroy him,’ yet she fights anyway, with her horn ‘burning and shivering like a butterfly.’

Combined with the fire of the Red Bull, this image is suggestive. There is a small Mattei urn portraying an image of love holding a butterfly close to a flame. This visually represents the purification of the soul by fire represented in Romanesque art by the burning ember placed by the angel in the prophet’s mouth.

Having driven the Red Bull into the sea, the unicorn then stands guard over Lír’s dead boy ‘as he had guarded the Lady Amalthea.’ She then brings him back to life: ‘her horn glanced across Lír’s chin as clumsily as a first kiss.’ As he looks into her eyes, he remembers Lady Amalthea. She leaves, and watching her go for a moment, ‘he looked like Haggard,’ crying out ‘she is mine!’

But then his voice softens: ‘I have no wish to capture her, but only to spend my life following after her.’ This, Lír believes, ‘is my right. A hero is entitled to his happy ending, when it comes at last.’ But the magician tells him, ‘You have loved her and served her—be content, and be king.’

This is not what Lír wants, but once more duty calls. “So be it. I will stay and rule alone over a wretched people in a land I hate.” As he watches the unicorn leave, with the memory of Lady Amalthea lingering in his heart, he says, “It’s strange to have grown to manhood in a place, and then to have it gone, and everything changed—and suddenly to be king.”

C.S. Lewis once remarked that fairy tales best say what needs to be said. And the magician, watching Lír bereft but not broken at the end, reminds us that “great heroes need great sorrows and burdens, or half their greatness goes unnoticed. It is all part of the fairy tale.”

One of my favorite films. I never realized all this in my head- yet I think there's also something instinctive about such beauty realized. You can understand it even before the mind has grounded it. Thank you for enriching my appreciation!