N.B. The talk I gave on this topic at the Renaissance of Men Conference will soon be available on Vimeo as a pay-per-view video.

Resilience means, literally, an ‘act of rebounding or springing back.’ The ultimate example of this is Christ’s Resurrection — rebounding from death itself. And one of the obstacles to resilience is fear. What if we can’t rebound? What if we can’t spring back? Even Christ was afraid before his Passion.

This is why resilience is related to fortitude, one of the four cardinal virtues: prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude. Cardo is Latin for hinge, and the moral life of man hinges on these virtues. Derived from fortitudo (‘manliness’), from fortis (‘strength’), fortitude makes a person unshaken from the doing the right thing by danger or difficulty. Without it, none of the other virtues is possible. The judge who is afraid to make the right call won’t exercise justice.

Accordingly, since ancient times, the education of boys has always involved physical hardship to develop fortitude. As Scripture says, ‘the life of man is a warfare’ (Job, 7:1), and fortitude moderates our fear and confidence in the battles we must face. Without it, we fall into either cowardice (too much fear, too little confidence) or rashness (too little fear, too much confidence).

Fortitude thus requires greatness of soul. This makes us love the best things and despise all that is opposed to them. It also requires greatness of deed. This make us perform generously what was nobly willed. And it requires endurance. This requires patience (not being thrown into dejection by difficulties) and steadfastness (refusal to accept defeat, surrender principles or make peace with wrong.

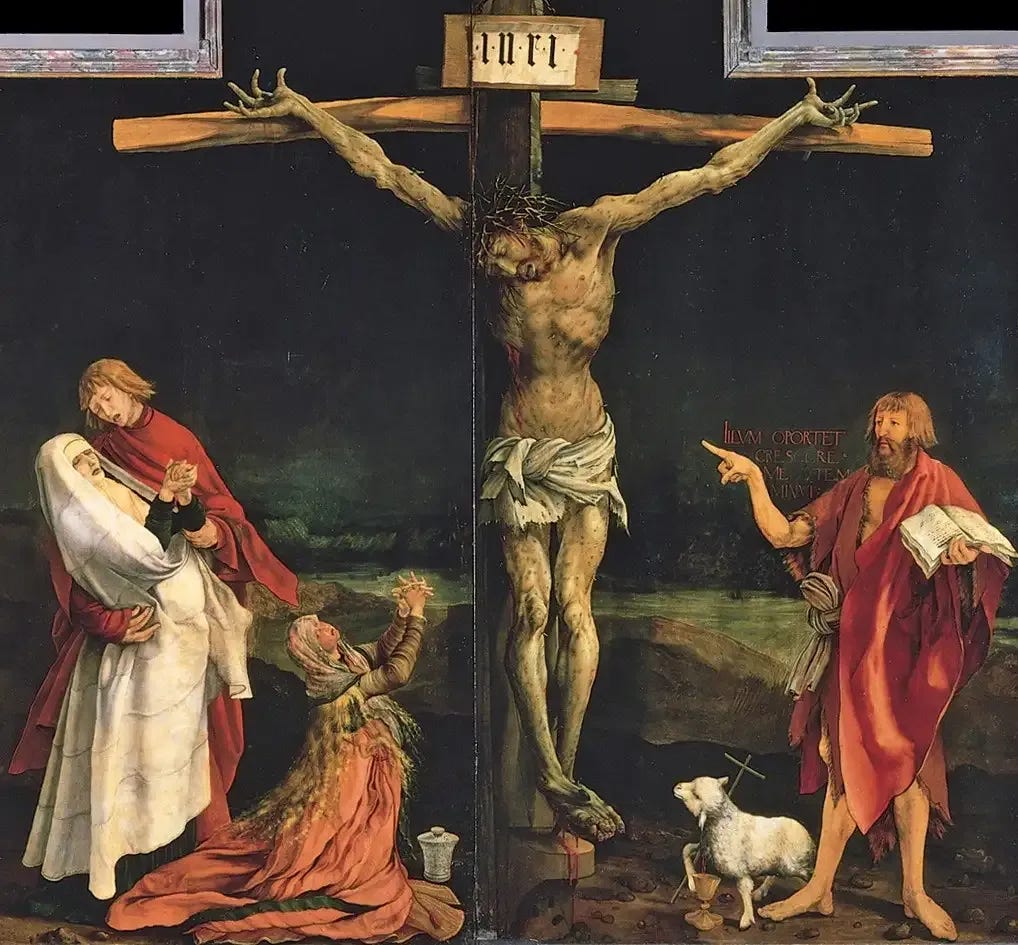

Christ’s Passion is the supreme example of all these: greatness of soul, greatness of deed, patience, and steadfastness.

Various vices, then, are opposed to fortitude.

The pusillanimous (little souled) man doesn’t desire great things.

The mean man won’t perform noble works on a grand scale.

The cowardly man doesn’t dare when he should.

The impatient man, unable to endure, complains and suffers excess of sorrow.

But for thinking about resilience, two vices are salient. The timorous man fears too much. And the effeminate man, distracted by pleasure or deterred by pain, lacks the stamina to go on in a necessary good. He surrenders to weariness or opposition by abandoning the undertaking or taking up with evil.

The ultimate display of fortitude is martyrdom because it’s the voluntary acceptance for the sake of God of a violent death inflicted out of hatred of virtue. In addition to this red martyrdom, however, the Church also recognises white martyrdom — being persecuted for the faith without shedding blood. In the age of cancel culture, it behoves us to apply the spiritual lessons the red martyrs have to teach us about facing the consequences of living in the truth.

Tribulation and The Great Turk

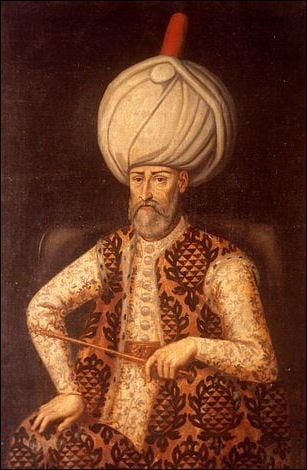

Thomas More wrote A Dialogue of Comfort in Tribulation in 1534/35, while he was in the Tower of London awaiting execution. Set in Hungary in the years 1527–1528, the dialogue shows a society on the verge of collapse. The Turks defeated the Hungarian army in battle in 1526, and the final Turkish invasion by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1529 led to permanent Turkish occupation. In the dialogue, the 'Grand Turk' is sometimes the literal Suleiman the Magnificent; sometimes he is Henry VIII; sometimes he is the Devil himself. Similarly, the ‘Turkish invasion’ is the literal historical event, the chaos of the English Reformation and, universally, the forces of chaos and evil.

For us, it comes wrapped in a rainbow flag, and it’s important to understand that you don’t get to choose your dragon. A man must fight the battles that come to him.

The two speakers are a wise, virtuous old uncle named Anthony and his nephew named Vincent, a young man seeking counsel. How should a man face the Grand Turk? In answering that question, More explains what it cost him — physically, mentally and spiritually — to get to the point where he could face his execution with serenity.

Knowing that many of his friends and family would be tortured or killed, he wrote the work to help them be resilient but without giving them false comfort. So although the book is organised around the three Theological Virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity, it also deals with their opposites: doubt, fear, despair, suicide, pride, hate.

It reminds me of the Blessed Virgin’s words to King Alfred battling the Great Turk in the form of the Danish invasion in Chesterton’s The Ballad of the White Horse:

I tell you naught for your comfort,

Yea, naught for your desire,

Save that the sky grows darker yet

And the sea rises higher.

In many ways, this is our situation today: how should good men face a bad world?

Vincent describes the atrocities of the Turks and complains to Anthony that 'so great perils appear here to fall at hand, that methinketh the greatest comfort that a man can have is when he may see that he shall soon be gone.’ Defining tribulation as ‘nothing else but some kind of grief—either pain of the body or heaviness of the mind,’ Anthony then reminds Vincent that the pains of Hell are far worse.

And he stresses that faith is the necessary foundation without which comfort is impossible: God comforts man. Unable to bear tribulation without God, even the Stoic sages killed themselves. Suicide is the biggest killer of young men today, and Stoicism is regarded as masculine by many, so this is a timely point. As Augustine remarked, the Stoics in their ‘stupid pride’ thought they could endure suffering without God. And they were wrong.

Having established faith as the foundation, Anthony then answers all Vincent’s anxieties. The Dialogue is over 300 pages and I recommend that you read it all, but I would like to emphasise the following fifteen lessons in particular.

#1: Tribulation is Good

God sends tribulation as a means for man's amendment, so we mustn’t desire it be taken away in every case. Indeed,

‘Every tribulation which anytime falleth unto us... is either sent to be medicinal if men will so take it... or may become medicinal if men will so make it... or is better than medicinal but if we will forsake it.’

Tribulation, then, is the bitter medicine that heals us. And there are three reasons it comes:

Because our own sinful deeds bring it upon us.

Because God sends it as a punishment for past sins or to preserve us from falling into sin.

Because it can help us prove our patience or increase our merit.

There are thus extremely good reasons why an all-good, all-powerful God would permit suffering and evil. No pressure, no diamond.

#2: Tribulation is The Way to Heaven

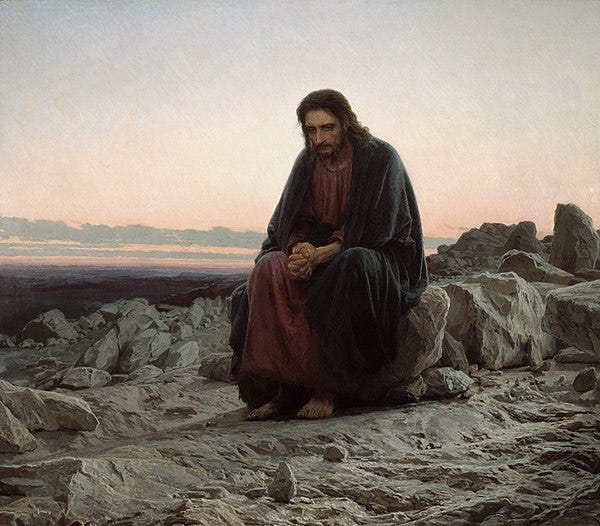

Tribulation teaches us to pray. Anthony remarks that Christ’s greatest prayers were those ‘He made in His great agony and pain of His bitter Passion.’ Tribulation is a gift — ‘the thing by which our Savior entered his own kingdom…the thing without which no man can get to heaven.’

And this is why recreation and attempts to divert from tribulation, although necessary due to the weakness of human nature, should be kept as short as possible. The lack of tribulation harms us.

Men should not seek soft lives.

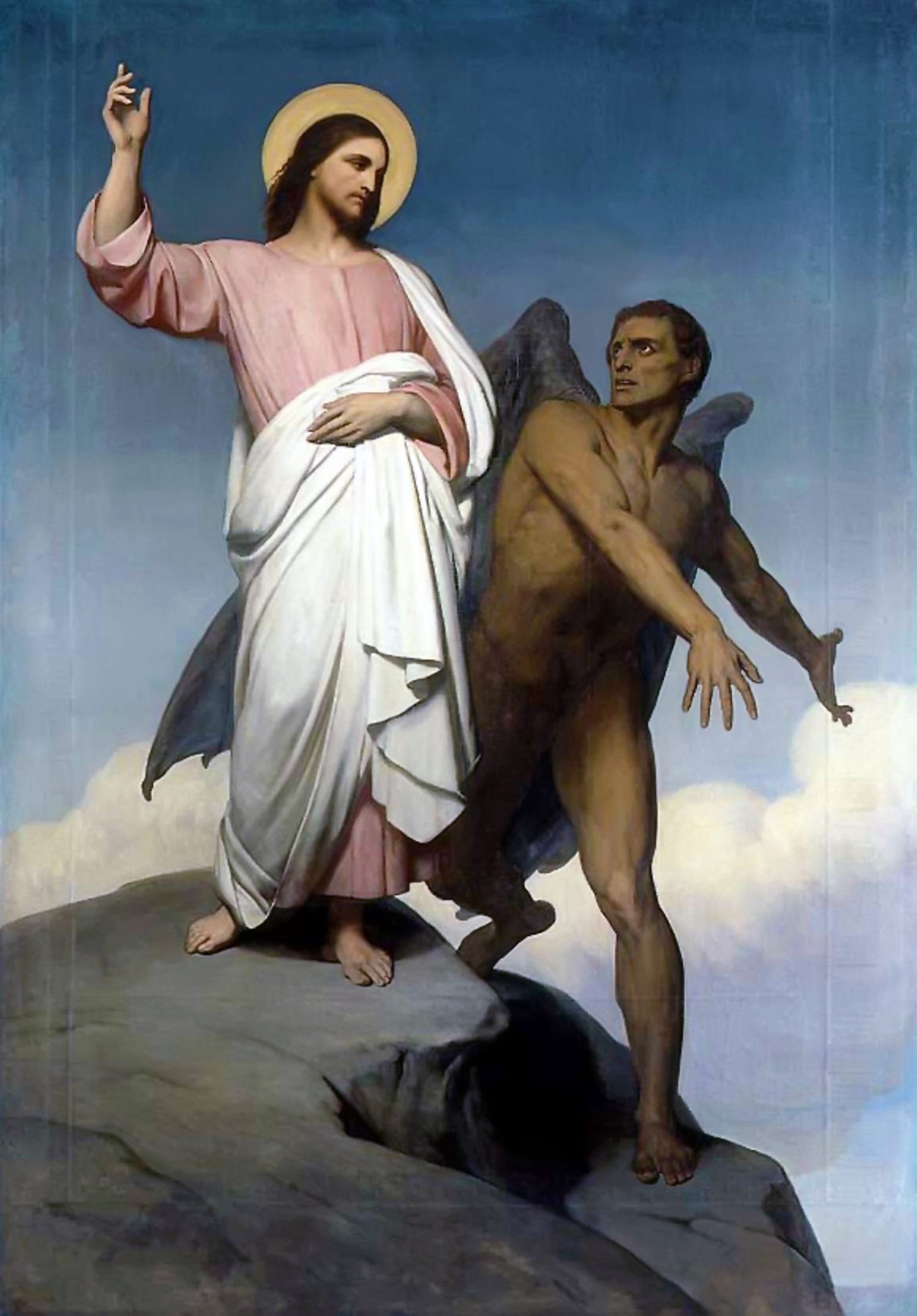

#3: Wrestling with the Devil

Sometimes we have tribulation we can’t avoid — getting sick, or example, or our loved ones dying. We can also deliberately impose it on ourselves by self-denial. But sometimes we face persecution we are reluctant to endure but do so to avoid giving displeasure to God. This is about integrity and honour. And because it involves open temptation by the Devil, it can aid our salvation if we wrestle with him.

Anthony uses Psalm 90 to explain the four kinds of wrestling:

"He that dwelleth in the aid of the most High, shall abide under the protection of the God of Jacob…His truth shall compass thee with a shield: thou shalt not be afraid of the terror of the night. Of the arrow that flieth in the day, of the business that walketh about in the dark: of invasion, or of the noonday devil."

These, then, are the four ways the Devil tempts us in tribulation:

The terror of the night

The arrow that flieth in the day

The business that walketh about in the dark

The noonday devil

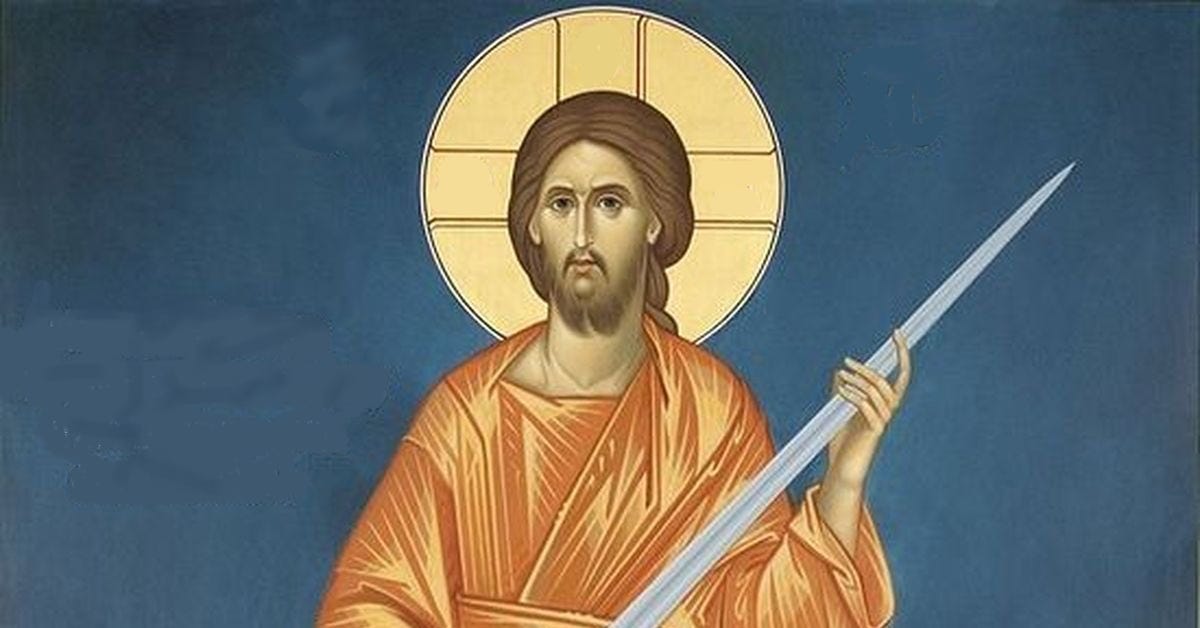

In all these cases, Christ is the shield — ‘broad above with the Godhead,’ as St Bernard says, 'and narrow beneath with the manhood.’ Without Him, a man is stripped back to his own powers of intellect and will that were weakened already by original sin and weakened further by actual sin.

#4: ‘The Night’s Fear’

The first temptation is called ‘the night’s fear’ for two reasons:

The tribulation is dark and unknown.

The dangers of the temptation are often greatly exaggerated.

It tempts us to impatience and anger (e.g., the sufferings of Job). But it also takes the form or pusillanimity (faintheartedness), which is littleness of soul — not desiring great things when one should desire them. This turns us away from noble pursuits. The Scriptures reprove Jonah for fleeing from the great task set before him by God. In its most serious form, as Vincent and Anthony discussed at the start, it’s the desire to kill oneself.

Cancel culture is the night’s fear in that it’s like the bump in the night that makes the timid man hide under the covers. If it works, it’s a symptom of spiritual sickness rather than a cause of it. As Augustine says in The City of God, ‘we detect weakness in a mind which cannot bear physical oppression of the stupid opinion of the mob.’

#5: ‘The Arrow Flying in the Day’

This is ‘the arrow of pride.’ Because man isn’t susceptible to pride in the night of tribulation and adversity, this arrow flies in the day of prosperity, when man is ‘full of lightsome lust and courage.’

When we are at our strongest, the Devil knows we are also at our weakest because we don’t think we need God. It involves vainglory, arrogance, contempt for the poor, and oppression and extortion. Anthony says good men in power should stay in their positions of authority for the common good but seek counsel to overcome this temptation.

#6: ‘The Business Walking in the Darkness’

Anthony interprets this as being a devil that tempts men to evil business or frantic activity in pursuit of worldly goods and pleasures. This is about inordinate desire for riches. Christ did not condemn riches as such — just the disordered attachment to them. Scripture doesn’t say money is the root of evil. It says the love of money is.

In this sense, unbridled capitalism has produced a generation of men whose honour and integrity had a price. We must remember that, after a man has provided for the material needs of his family, obsessing about work can emasculate him by distracting from his more important duties.

#7: ‘The Incursion of the Noonday Devil’

At this point, news of the Turkish invasion arrives, and Anthony says that God makes ‘these infidels…the sorrowful scourge of correction.’ He uses them to illustrate 'the incursion of the noonday devil’. Whereas in all the other temptations the Devil ‘stealeth on like a fox,’ in this temptation ‘he runneth on roaring with assault, like a ramping lion.’

And it’s the most perilous because it involves the Devil tempting with not only the promise of peace and prosperity but also terror. A man ‘may for the forswearing or the denying of his faith be delivered and suffered to live in rest, and some in great worldly wealth also.’ Just say men can get pregnant and they’ll leave you alone. Just add your pronouns to your email signature and get the promotion.

Combined with the threat of imprisonment, torture and death, the promise of prosperity is ‘a marvelously great occasion’ for falling into the Devil’s trap. It’s a pincer movement of the promise of both pleasure and pain.

#8: Fear God only

Since man is both body and soul, all harms must involve one of these two. And Anthony says the soul is harmed only by disordered attachment to the body that leads to sliding from the Faith. That is why we are told, “Fear God and keep His commandments, for this is all man.” (Ecclesiastes 12:13)

Fear of anything other than God is emasculation.

There is much that Vincent fears. A man stands to lose all his money and property, reducing him to the shame of begging. He must also suffer ‘the grief of heart’ in watching other good men suffer while his enemies ‘enjoy the commodities that himself and his friends have lost.’ After losing all this, he can also lose his life.

But Anthony’s ultimate response to this is that we cannot keep any of our possessions — or our lives — for very long. And they can harm a man’s soul by puffing him up with pride, which is far more dangerous than any bodily harm.

#9: No Shelter Under the Dragon’s Wing

But what, Vincent asks, if a rich man says he will profess Islam in name only? Why not try to appease the Great Turk? Anthony responds by quoting Christ: ‘No man may serve two lords at once.’ We must publicly profess our faith. To forsake the faith on one point is to forsake it entirely.

And, crucially, the Turk demands total submission anyway. Anthony warns that the Turk would not leave you after he had ‘once brought you so far forth... but would little and little after, ere he left you, make you deny Christ altogether, and take Muhammad in his stead.’

Appeasement only emboldens. Instead, Anthony tells Vincent to think of how Christ expressed fear at His own Passion but showed courage.

Once you’re on your knees, you never get back up.

#10: The World as Prison

Vincent is scared of imprisonment, but Anthony says that God will be with them in prison as much as he is with them now.

He then provides three more reasons why Vincent should not be afraid.

We only fear loss of liberty because we imagine we have more than we do. Human laws restrain us, and we are all in bondage to sin.

The world itself is a prison — a theme that echoes Plato's Allegory of the Cave. In fact, ‘the great Turk, by whom we so fear to be put in prison, [is] in prison already himself.’ He is like a rich man condemned to death but given the use of his lands and free access to his family and friends until his execution.

Since ‘Our Savior was himself taken prisoner for our sake,’ we mustn’t fear it.

Regarding the point about imagining we have more liberty that we do, intellectuals afraid to lose their jobs for not paying lip service to lies should imagine the prospect of a career of soul-destroying cowardice instead.

#11: What Did You Expect?

Vincent worries Christians will renounce Christ rather than suffer a shameful death. But Anthony responds that no death suffered for Christ is shameful.

It is ‘very precious and honorable in the sight of God, and of all the glorious company of heaven.’ For the apostles, suffering for Christ was a ‘great glory.’

And Christ emptied Himself of His divinity and suffered the humiliation of Crucifixion for us. Since the ‘servant is not above his master,’ we must not ‘disdain to do as our Master did.’

He ‘through shame ascended into glory,’ so we would be mad to ‘fall into everlasting shame both before heaven and hell than, for fear of a short worldly shame, to follow him into everlasting glory.’

#12: Success in This Life Doesn’t Determine Success in Life

Vincent worries that pain, unlike shame, can’t be mastered, but Anthony responds that God will give us grace to strengthen us. And not only is death from sickness and disease often more painful and more prolonged than a violent death, but the pains of Hell are everlasting. Nothing the Turk can do compares to them.

Against the joys of Heaven we must ‘set at naught all fleshly delight, all worldly pleasures... all earthly losses, all bodily torment and pain.’

#13: No Guts, No Glory

Anthony cites the words of Christ to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:26): 'Ought not Christ to have suffered these things, and so to enter into his glory?’

It is shameful, says Anthony, to desire ‘to enter into the kingdom of Christ with ease, when himself entered not into his own without pain.’ We must meditate on Christ’s passion and be both inspired and humbled by the fact that many of the martyrs of the past were ‘not only men of strength, but also weak women and children.’

Indeed, trust in God means the Turk, His scourge, may do us ‘inestimable good.’

#14: Our Enemy is Immortal

Anthony reminds Vincent that the literal Turks are only the instruments of the Devil. As St. Paul says, “Our wrestling is not against flesh and blood.” (Eph. 6:12)

Anthony recommends continually keeping this in mind:

‘If the devil put in our mind the saving of our land and our goods... let us remember that we cannot save them long.’

‘If he fear us with exile, and flying from our country, let us remember…whithersoever we go, God shall go with us.’

‘If he threaten us with imprisonment... let us tell him we will rather be man’s prisoners a while here in earth... than by forsaking the faith, be his prisoners ever in hell.’

‘If he put in our minds the terror of the Turks... let us consider his false sleight therein. For this tale he telleth us to make us forget him. But let us remember well that in respect of himself, the Turk is but a shadow. They are but his tormentors; for himself doth the deed.’

The so-called culture war is really a spiritual war, and what’s really at stake is our souls.

#15: You Didn’t Get Subverted. You Sinned.

Only by living in truth is a man saved. Anthony reminds Vincent that the Devil ‘never runneth upon a man to seize on him with his claws till he see him down on the ground willingly fallen himself.’

When predators want to attack a herd, they first spook it. Similarly, the Devil sets his servants against us to make us fall through fear. Meanwhile, the Devil ‘compasseth us, running and roaring like a ramping lion about us, looking who will fall, that he then may devour him.’

This is why we must fear God only. And Anthony’s advice to avoid falling due to fear is that we tell the Devil ‘that our Captain, Christ, is with us, and that we shall fight with his strength that hath vanquished him already.’

Finally, Anthony asks God to ‘breathe of his Holy Spirit into the reader’s breast, which inwardly may teach him in heart, without whom little availeth all that all the mouths of the world were able to teach in men’s ears.’

TLDR

The hardest lessons to learn from this book are also the most important:

#9: There is no shelter under the dragon’s wing. No happy-ever-after awaits you for kneeling to lies. Even the informants in the Soviet Union were sent to the Gulags in the end.

#12: Success in this life doesn’t determine success in life. ‘What should it profit a man if he gains the whole world but loses his own soul?’

#13: No guts, no glory. Christians, as Pope Leo XIII said, are ‘born for combat.’ It’s easy to read about Alexander the Great or Vikings. It’s a lot harder to face the fact that your dragon comes to you wrapped in a rainbow flag and offers you worldly success.

#15: You didn’t get subverted. You sinned. Victim narratives are emasculating.

Can you discuss a bit more about stoics killing themselves. Stoicism is making a resurgence and I’d like to be able to speak intelligently about it.