John Keats (1795 – 1821) wrote some of the best poems in the English language during his short life. ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’ (‘The Beautiful Lady without Mercy’) warns against the dangers of simping — infatuated men no longer leading but becoming besotted followers, inverting the proper hierarchy of the sexes.

The poem begins with the speaker encountering a sick knight:

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

‘Loitering’ means the knight is idle, dawdling — alone by the lake for no obvious reason. He has forgotten his mission: being ‘the armed Force in the service of the unarmed Truth’, as Gautier defined ‘the true idea of chivalry.’ Thus new knights received gold spurs to remind them of being obedient to the Divine Will. But this knight no longer heeds it. The birds, a traditional link between heaven and earth and the symbol of the Holy Spirit, are silent.

This means he has lost his place in the order of things:

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

Knight were responsible for the training of not only horses but also hawks, and an untamed one was known as ‘haggard’. This knight, then, has gone wild — forgotten his training and discipline. But ‘haggard’ also suggests his gaunt, emaciated condition in contrast to the ‘full’ granary of the squirrel and the gathered harvest. He is ‘woe-begone’ because the loss of his mission means misery.

Not only misery, in fact, but death:

I see a lily on thy brow,

With anguish moist and fever-dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

Because it’s pale white, the lily is often associated with death: it’s still used at funeral services today. The knight’s ‘anguish moist and fever-dew’ show he’s sick, and the rapidly ‘fading rose’ of the colour in his cheeks suggest he might die soon. But what is it that ails him?

Finally, the knight speaks:

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

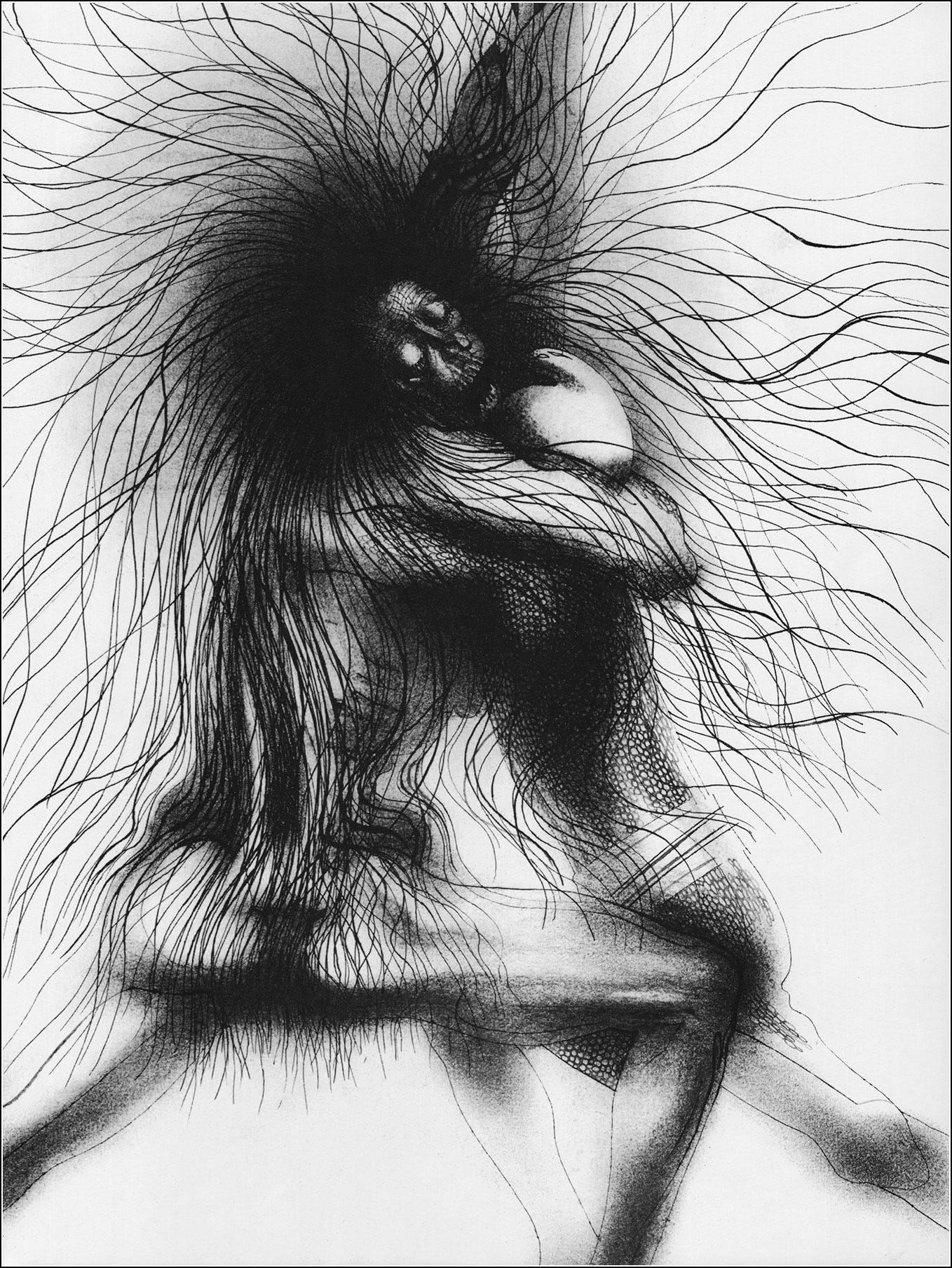

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

The ‘meads’ are the meadows — wild grassland symbolising unrestrained nature. In mythology, the earth is feminine: Mother Nature represents fecundity and fertility. And the dash before ‘a faery’s child’ shows the knight is lost for words at the lady’s bewitching beauty. Her ‘wild’ eyes lure him.

Lovestruck, he makes gifts for her:

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan

He crowns her with the ‘garland’ but then moves down to ‘bracelets too’ and finally the ‘fragrant zone’, a girdle of flowers for her waist. But a girdle is also something that confines, and to girdle a plant is to cut away the bark and cambium in a ring to kill it by interrupting the circulation of water and nutrients. And the knight’s focus on the ‘fragrant zone’ of her hips (suggesting sex) indicates how lust now begins to girdle him. ‘She looked at me,’ he says, ‘as she did love’: he sees what he wants to see.

Just as Keats inverted the ‘haggard’ hunting hawk to apply to the wayward knight himself, he now inverts the knight’s horse, too:

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

The lady — or lust — is in the saddle now. Indeed, his setting her on his ‘pacing steed’ might be a euphemism for sex, given her ‘sweet moan’. And now he is so hypnotised by her ‘faery’s song’ that he sees ‘nothing else … all day long’. Odysseus had to tie himself to the mast to resist the song of the Sirens, but the lady has overpowered the knight.

Gratifying his appetites, she feeds him:

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna-dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

‘I love thee true’.

The dream vision he has later suggest these ‘roots’ might be psychedelic, but regardless ‘the honey wild’ echoes her ‘wild eyes’ and the untamed meadows. Regarded as an aphrodisiac for centuries, the honey is juxtaposed to the ‘manna-dew’ that recalls his ‘fever-dew’. This links his lust to his sickness. Although the Israelites fed off manna in the desert, Jesus reminds us in the Gospel of John that they eventually died. Only his bread gives everlasting life.

Similarly, the knight’s story shows that the most delicious pleasures can be a doorway to death:

She took me to her Elfin grot,

And there she wept and sighed full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

A ‘grot’ is a cave, and the dark earth-mother — the Diana of Ephesus — was depicted, Cirlot notes in his Dictionary of Symbols, with black hands and face, recalling the black openings of caves and grottos.' Like Beowulf facing Grendel’s mother in the underwater cave, the knight here confronts the feminine that threatens to overpower him.

But whereas Beowulf manages to throw off the hag when she sits on top of him (Beowulf’s steed isn’t for riding), the lady here sighs ‘full sore’ as her eyes, intensifying, now become ‘wild wild’.

Perhaps she weeps because she knows what’s coming:

And there she lullèd me asleep,

And there I dreamed—Ah! woe betide!—

The latest dream I ever dreamt

On the cold hill side.

To ‘lull’ is to soothe, relaxing vigilance, contrasting to Christ’s command to ‘stay awake’. And in this sense the lady is like Calypso, who ensnares Odysseus. A sex-starved nymph, she keeps him on her island for seven years. Her name comes from the Greek kalyptein, which means to cover or conceal. Odysseus later understands her embraces were to “banish from my breast my country’s love” — that is, distract him from his mission to get home.

Calypso cloaks his destiny with carnality. Thus when he breaks free, it's an apocalypse — literally, an uncovering or unveiling. Without this breaking free, however, there is only ‘woe’, and the beauty of the meadows becomes the ‘cold hill side’.

The knight has a vision of simps stretching back to the beginning of human history:

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Thee hath in thrall!’

King, princes and warriors — symbols of patriarchal order — are all here in ‘thrall’ to her, meaning not just in servitude or submission but also absorption, mental and moral. Note the repetition of ‘pale’ echoing the knight ‘palely loitering’ at the beginning of the poem. A master of the music of the English language, Keats subtly rhymes ‘all’/‘thrall’ to draw our attention to the power the men’s lust gives the lady, making them place her above God.

Echoing the eating and drinking from earlier, Keats then shows how she can’t ultimately satisfy them:

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gapèd wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

As Aquinas warns, 'the love of bodily pleasures leads man to have a distaste for spiritual things, and not to hope for them as arduous goods. In this way, lust causes despair.' (ST 2-2.20.4). And the ‘gloam’ is richly suggestive here. It means not only twilight or a liminal state but also a period of decline. It’s a vision of the decline of male authority as men putting women above God brings the twilight of civilisation and the knight is left ‘loitering’ on the limen.

But he knows he won’t be loitering long:

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

‘Sojourn’ shows he knows this is just a temporary stop: death awaits him, as it does all who fall into the honeytrap this poem warns against. That’s why knights were given not only gold spurs but also — the central inversion of the poem — a white girdle to remind them of the importance of chastity.

Suggests deeper connotations for the expression “white knight” too

Wonderful breakdown of a greatly relevant poem