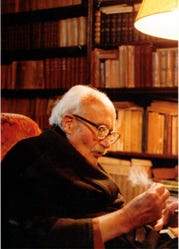

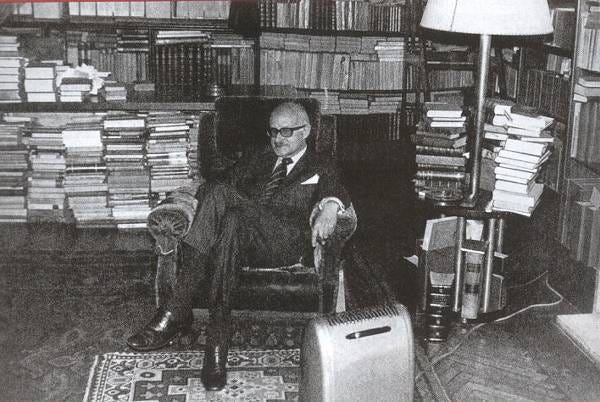

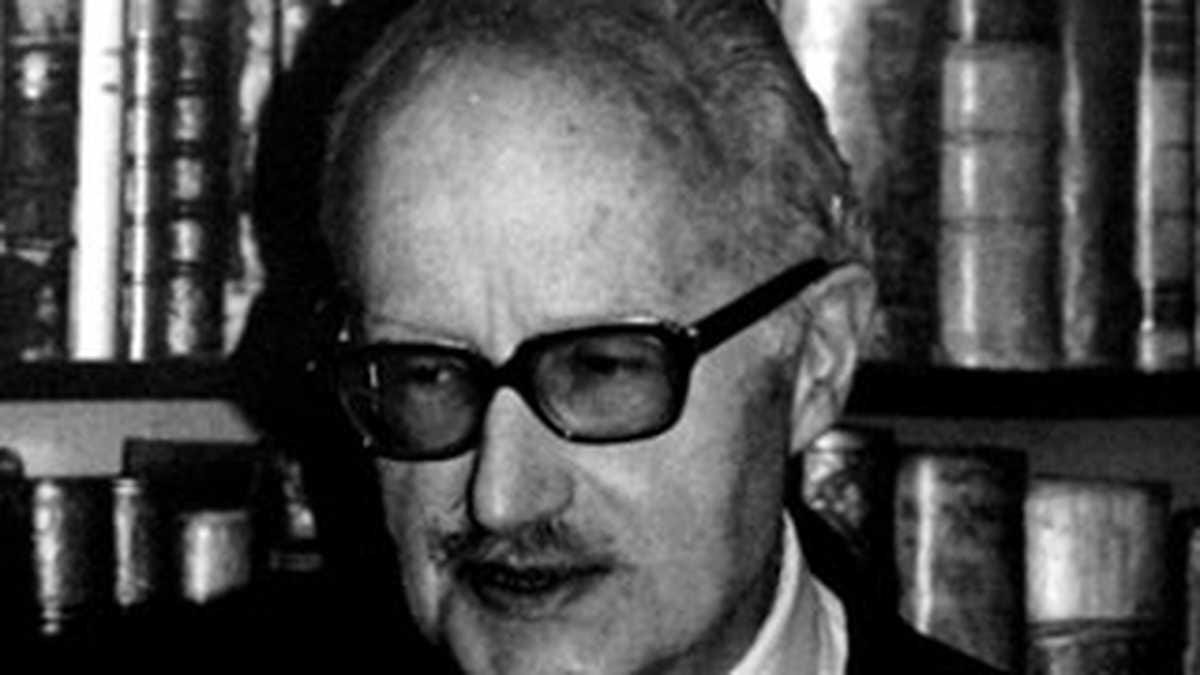

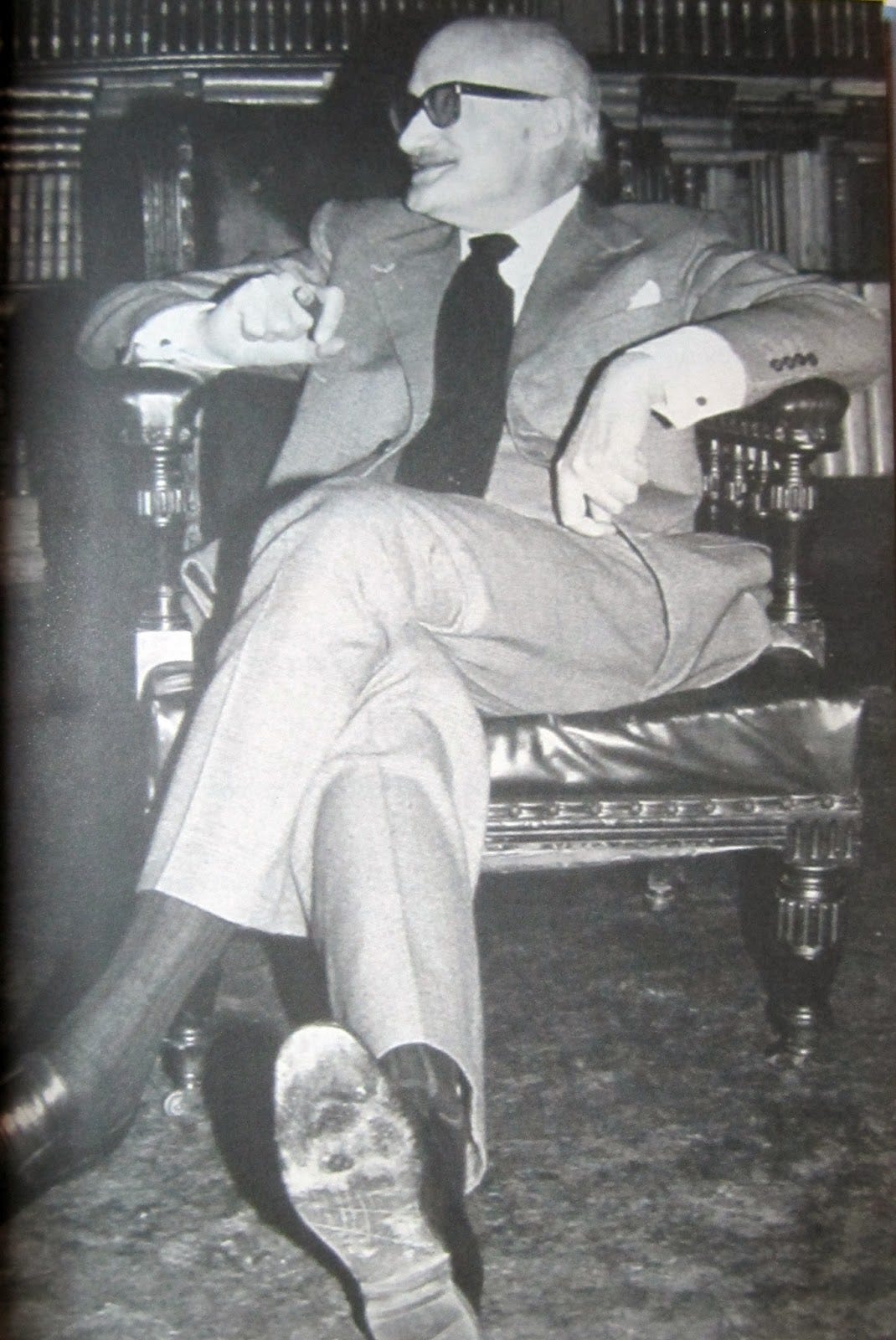

The Columbian philosopher Nicolas Gómez Dávila (1913-1994) was taught Latin, Greek and the classics by private tutors, never went to university and then, living mostly as a recluse, rarely left his library of over 30,000 books on the history of the West. His friends called him ‘Don Colacho.’ President Alberto Llera offered him a position as an adviser in 1958, and he was also offered the position of Colombian ambassador at the Court of St. James in 1974. He declined both.

His reading and The Violence — a ten-year period where Colombian liberales and conservadores killed each other — formed his view that the fundamental divide in society is between progressive and reactionaries. He was reluctant to publish his work during his lifetime, and it consists almost entirely of thousands of aphorisms. Each one says more than most writers say in a book, and the aim of this brief overview is to win him more readers.

Although there is currently no study of his work in English, few writers are more important now. A good test of a thinker is what he has to say about sex, and Don Colacho doesn’t disappoint: ‘sexual promiscuity is the tip society pays in order to appease its slaves.’ Indeed, ‘to liberate man is to subject him to greed and sex.’

And so ‘modern man’s life oscillates between two poles: business and sex.’ Particularly scathing about the involvement of both in porn, he writes that, ‘the ability to consume pornography is the distinctive characteristic of the imbecile.’ This is because ‘whatever is labeled “for adults,” is not meant for adults.’

But ‘in the society that is starting to take shape, not even the enthusiastic collaboration of the sodomite and the lesbian will save us from boredom.’ This is because ‘immodesty is the solvent of sensuality’. And ‘the most recent generations are particularly boring: believing in effect that they invented violence and sex, they copulate doctrinairely and doctrinairely kill.’

But ‘despite what is taught today, easy sex does not solve every problem.’ Indeed, ‘sex does not solve even sexual problems’. Don Colacho sees there is no such thing as safe sex, and ‘the purpose of sex education is to make it easier to learn sexual perversions.’ Ultimately, ‘the problem is not sexual repression, nor sexual liberation, but sex.’

He recognises, however, the reality of the wayward human will — ‘a motto for the young leftist: revolution and pussy’ — and says that ‘the root of reactionary thought is not the distrust of reason, but the distrust of will.’ Thus ‘being reactionary is understanding that it is not possible to demonstrate or convince, only to invite.’ He also says, wisely, “I distrust every idea that doesn’t seem obsolete and grotesque to my contemporaries.”

Another good test of a thinker is what he has to say about God. Don Colacho doesn’t disappoint here either. ‘The death of God is an interesting opinion, but one that does not affect God,’ he writes, adding elsewhere that ‘cultures dry out when their religious ingredients evaporate’ and ‘an irreligious society cannot endure the truth of the human condition. It prefers a lie, no matter how idiotic it may be.’

Indeed — and think here of equality, diversity and inclusion — ‘the simplistic ideas in which the unbeliever ends up believing are his punishment.’ For Don Colacho, ‘modern history is the dialogue between two men: one who believes in God, another who believes he is a god.’ In this sense, then, ‘the modern world shall not be punished: It is the punishment.’

Thus ‘violence is not necessary to destroy a civilization. Each civilization dies from indifference toward the unique values which created it.’ And here Don Colacho is especially attentive to the necessity of hierarchy. ‘In society just as in the soul, when hierarchies abdicate the appetites rule.’ (As Plato said, the city is the soul writ large.) By contrast, ‘relativism is the solution of one who is incapable of putting things in order.’

Don Calacho’s insights here are prescient. ‘Every straight line leads right to a hell’ is a reminder of the dangers of the reductionism of the revolutionary. The progressive concept of equality perverts the Christian idea that all men are equally made in the image of God because it neglects that ‘hierarchies are heavenly. In hell, all are equal.’

Thus ‘levelling is the barbarian’s substitute for order,’ and in fact ultimately ‘every non-hierarchical society splits in two’. Accordingly, 'in the modern state there now exist only two parties: citizens and bureaucracy.’ And ‘individualism is not the antithesis of totalitarianism but a condition of it. Totalitarianism and hierarchy, on the other hand, are terminal positions of contrary movements.’

Another way of putting this is that ‘doctrinaire individualism is not dangerous because it produces individuals but because it suppresses them. The product of the doctrinaire individualism of the 19th century is the mass-man of the 20th.’

The unifying value for progressives is equality; reactionaries are simply against this. By contrast, ‘today’s conservatives are nothing more than Liberals who have been ill-treated by democracy.’ Mainstream conservatism shares the fundamental assumptions of liberalism, and in fact capitalism is merely economic liberalism: ‘The Gospels and the Communist Manifesto are on the wane; the world’s future lies in the power of Coca-Cola and pornography.’

Indeed, ‘tolerance consists in the firm decision to allow the others to scoff at everything that we pretend to love and respect, provided that they do not threaten our worldly comfort. As long as others do not tread on his corns, modern man—liberal, democrat, progressivist—tolerates them to besmirch his soul.’

This is intellectually and spiritually deadening. ‘The taste of the populace is not characterized by their dislike of excellence but by the passivism with which they delight equally in the good, the mediocre, and the inadequate. The populace does not have bad taste—it is, simply, tasteless.’ Yet again, the barbarian levels rather than orders.

Don Colacho believed that ‘the cause of democracy’s stupidities is confidence in the anonymous citizen; and the cause of its crimes is the anonymous citizen’s confidence in himself.’ In fact, ‘democracy is the political regime in which the citizen entrusts the public interests to those men to whom he would never entrust his private interests.’

If there is a thoughtlessness to this, it’s because ‘ideologies were invented so that men who do not think can give their opinions.’ Hence the reliance on statistics in the mass media that substitutes for thinking in a democracy: ‘statistics is the tool of those who give up understanding in order to manipulate.’ In this sense, ‘daily news is the modern surrogate of experience.’ Ironically, then, despite his ideology of autonomy, ‘modern man accepts any yoke, as long as the hand imposing it is impersonal.’

His comments on rights were particularly prescient. Traditionally, he notes, a man ‘has no more right than that which he derives from another’s duty.’ A right is something owed to another. Rights are thus communal, not individual. But today “it has become customary to proclaim rights in order to be able to violate duties.’ Thus ‘the tissues of society become cancerous when the duties of some are transformed into the rights of others.’

The proliferation of rights is symptomatic because ‘dying societies hoard laws like dying people medicines.’ This reminds me of Chesterton’s aphorism that ‘over-civilization and barbarism are within an inch of each other.’ How can this be?

Tacitus, writing on Rome, provides illumination. ‘Once we suffered from our vices; today we suffer from our laws,’ he lamented (Annals, iii.25). Primitive cultures are ruled by custom. They are not legalistic. As their intellectual life develops, they then develop an understanding of why their customs are just. Their traditions are thus traced to natural and, ultimately, divine law.

But the merely legalistic society loses touch with this. For Don Colacho, remember, ‘cultures dry out when their religious ingredients evaporate’.

In the progressive wasteland, ‘the pure reactionary is not a dreamer of abolished pasts, but a hunter of sacred shades on the eternal hills…The reactionary does not aspire to turn back, but rather to change direction. The past that he admires is not a goal but an exemplification of his dreams.’ And there can be only one desirable direction: 'the Church is the sewer of history, the tumultuous flowing of human impurity towards immaculate seas.’