'Boys are always looking for ways to become men,' says Ed Gentry, the narrator of Dickey’s Deliverance. And so he and his three friends — Lewis Medlock, Bobby Trippe and Drew Ballinger — go into the wilderness. The comfort of civilisation, Lewis believes, is for 'lesser men':

'Life is so fucked-up now and so complicated that I wouldn't mind if it came down, right quick, to the bare survival of who was ready to survive…'

It’s the kind of elemental, mythical narrative that E. M. Forster said kept cave men ‘gaping around the fire.’ Overshadowed by its inferior film adaptation and banned in the past, however, the novel is rarely read today — despite being ranked at number 42 on Modern Library’s 100 Best Novels. It should be ranked higher. As a cautionary tale of the distinction between masculinity and machismo, it’s timelier than ever.

There are five sections: 'Before,' 'September 14th,' 'September 15th,' 'September 16th' and 'After.' Their descent — the three central days — thus takes place, symbolically, in the fall season. It’s a descent into hell, the Country of the Nine-Fingered People. The five sections parallel not only the five acts of a tragedy (the focus being, as Aristotle said, purgation) but also the archetypal stages of heroic myths.

But the film — by removing the first and final sections — reduces the mythic range of the novel, so this commentary will aim at elucidating it. If 'myth is always an account of creation,' in Mircea Eliade’s famous definition, then Deliverance is an account of the creation of masculinity and a warning about how it can degenerate into idolatry.

Teaching has taught me that merely giving someone a book to read isn’t enough. Readers also need a guide to help them see what matters and why. This, then, is a guided tour of a masterpiece. My hope is that it will inspire you to read the novel itself and enhance your understanding and enjoyment of it.

Before: Of Myths and Men

Lewis Medlock takes his three companions canoeing down the Cahulawassee, a river none of them had seen, in wild mountainous back-country. Soon, it is to be dammed up to create an artificial lake, so Lewis wants to test the group against it 'before the real estate people get hold of it and make it over into one of their heavens.' Why? 'Because it’s there'.

This, famously, is what George Mallory said about climbing Everest. And it’s the spirit of adventure and conquest that characterises the New World. Ed knows Lewis has a deeper purpose: 'Ah, he’s going to turn this into something, I thought. A lesson. A moral. A life principle. A way.' He’s right. Lewis, who talks 'continuously of resettling in New Zealand or South Africa or Uruguay', dreams of an existence where 'you could make a kind of life that wasn’t out of touch with everything, with the other forms of life'.

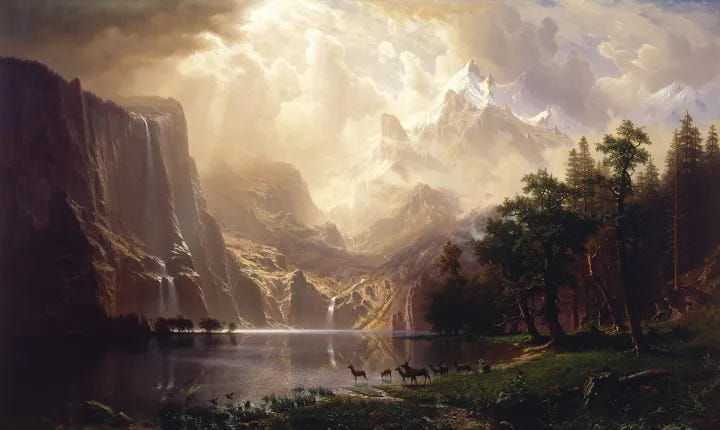

Lewis’s longing is the legacy of the spirit of America itself. In Regeneration through Violence (1973), Richard Slotkin emphasises the parallels between the passage from the known world to the unknown realm in the archetypal myth of the hero’s journey and the experience of the colonists in early American history. The self-reliant hero sets out to tame the wilderness and defeat its avatars in order to make a new life for himself. ‘America,' as Emerson put it, ‘is the idea of emancipation’.

Emancipation from what, though? A fitness fanatic, Lewis believes that 'the body is the one thing you can’t fake'. And Ed —reasonably happy, reasonably successful — is often panicked by the 'inconsequence' of anything he might usefully do in a few vacant minutes at the office.

Ed says he lives by 'sliding' — 'finding a modest thing you can do and then greasing that thing.' And a lack of competition, challenge and conflict means their lives, merely sliding by, are slipping away. This is the Unreal City of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land: ‘Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled, / And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.’ Not that they’ve read it. (They aren’t intellectuals, thankfully.) 'I don't read books and I have no theories,' says Ed. But you don’t have to have read Nietzsche for Nietzschean taedium vitae to vitiate your life.

Bobby and Drew, Ed notes, 'were day-to-day happy enough; they were not bored in the way Lewis and I were bored.' But ‘happy enough’ is hardly thriving. The threat of meaninglessness is there 'in the very bone marrow'. It’s what Ed calls 'the old mortal, helpless, time-terrified human feeling' that reduces him to feeling as 'impotent as a ghost, going through the only motions it has.'

‘Impotent’ is telling. Ultimately, it’s about emancipation from emasculation — the androgyny of ordinary, daily city life. On his way to work before the trip, Ed notices that he is surrounded by women: 'I was halfway up when I noticed how many women there were around me. Since I had passed the Gulf station on the corner I hadn’t seen another man anywhere.' He is 'filled…with desolation.'

The frontier had once made men feel meaningful. Untamed America had no Old World counterpart: Bradford, one of the earliest settlers, called it ‘hideous and desolate’. The transatlantic journey and subsequent western advances stripped away centuries. Survival depended on overcoming a wilderness as terrifying as that which confronted primitive man.

Conquest, then, was crucial: man as protector and provider. Hence the hero myth of the hunter — a figure that Slotkin argues is central in American mythology because of his simultaneous knowledge and control over the wilderness and his ability to mediate the contrast between culture and nature. And Lewis is 'one of the best tournament archers in the state'.

The hunter is the American equivalent of the European myth of the Faustian man. ‘The hero of the hunter myth is the representative of that spirit in us which demands that the frontiers of our knowledge and our control (the two go together) be ever extended into the unknown wilderness of the natural world, of the yet unrealised possibilities of our destiny’. Lewis, Ed says, is ‘always leaving, always going somewhere, always doing something else.’

So powerful is the hunter archetype that cowboys — who share the hunter’s rugged individualism and self-reliance — became a powerful American cultural symbol despite having only been around for roughly 20 years (c.1866-1885). Even after the invention of barbed wire made them redundant, they continued to ride the regions of the imagination as frontier symbols. The 1948 hit ‘Ghostriders in the Sky,’ for example, the greatest Western song of all time according to the Western Writers of America, describes the ghosts of doomed cowboys ‘trying to catch the devil's herd / Across these endless skies’.

But it was not only the unknown wilderness of the natural world. Prolonged exposure to the American wilderness, it was feared, might cause Europeans to degenerate by incorporating its savagery into their bodies and souls. Thus Joel Barlow’s ‘Columbiad’ (1807) describes how,

…old Europe's noblest pride,

When future gales shall wing them o'er the tide,

A ruddier hue and deeper shade shall gainAnd stalk in statelier figures on the plain.

Lewis, significantly, is ‘clay red’ — Barlow’s ‘ruddier hue’. ‘The essential American soul,’ D. H. Lawrence said, ‘is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer.’

‘Ghostriders,' interestingly, has been linked to the myth of the Wild Hunt: this, Susan Greenwood says, 'primarily concerns an initiation into the wild, untamed forces of nature in its dark and chthonic aspects.' Similarly, Joseph Campbell noted that, in myth, 'the regions of the unknown (desert, jungle, deep sea, alien land, etc.) are free fields for the projection of unconscious content … in forms suggesting threats of violence'.

‘Chthonic’ means infernal — related to the underworld. At night, Ed says, 'I went down deep, and if I had any sensation during sleep, it was of going deeper and deeper, trying to reach a point, a line or border.'

Deeper and deeper: the structure of Deliverance is the archetypal Descent and Return. Moby-Dick is in its lineage (and before that The Divine Comedy and The Odyssey), especially in its focus on water — a symbol of both death and rebirth. Origen, for example, associated the waters of the subterranean ‘deep’ with the Devil and his angels. In 1 Enoch, fumes arise in the valley of the fallen angels amid a ‘convulsion of waters’. And Romans 10:7 and Peter 3:19-21 associate Christ’s post-resurrection descent into Hades with ‘the deep’. But 'the river of the water of life' can also cleanse and renew.

American literature, intriguingly, introduced the sea story as a distinct genre: Cooper’s ‘The Pilot’ (1823) is unprecedented in that the ocean is the main setting and seamen the principal characters. Why the connection between America and the sea? To get to America in the first place, the Atlantic was the first frontier; the final one, at the extreme of Westward expansion, was then the Pacific (explored in Moby-Dick, the ultimate Western). As Charles Olson noted, ‘the Atlantic crossed, the new land America known, the dream’s death lay around the Horn, where West returned to East’.

There is also the fact that ‘the cruising of a boat here and there is very much what happens to the soul of man in a larger way’ (Belloc). And the settlers — surrounded by a new, dangerous environment — were both ‘all at sea’ (in danger) and ‘all in the same boat’ (intense fellowship). Like Melville’s Pacific and Conrad’s Congo in Heart of Darkness, Dickey’s Cahulawassee contrasts pastoral myths with primal realities.

‘The sea,' Dr. Johnson says in The Rambler 32, is not a subject of pastoral literature because it is ‘an object of terror’. And something similar could be said for the river. Etymologically, ‘terror’ is related to awe, and that is what Lewis and the gang crave. Terror is preferable to tedium; awe, to 'gray affable' men. It’s 'the kind of thing that gets hold of middle-class householders every once in a while,' Bobby says — weekend warriors.

Before their departure, Ed notes, ‘the day sparkled painfully, seeming to shake on some kind of axis, and through this a leaf fell, touched with unusual color at the edges. It was the first time I had realized that autumn was close.’ Symbolically, this is the Fall, and so the descent into the underworld — the axis — begins.

September 14: Departure

The first day thrills them as they realise that ‘the world is easily lost’. Ed, ‘tanked up with [Lewis’s] river-mystique,’ feels the pull of the wilderness:

We went over a bridge, and through the whirling girders of the supports the river was flickering. It was green, peaceful, slow, and I thought, very narrow. It didn't look deep or dangerous, just picturesque.

Although this aesthetic appreciation of the wilderness — 'the idea of hunting, for me, was also a kind of romance,' Ed says — is easy from a distance through a car window, the reality differs radically.

I can’t read ‘the river was flickering’ without thinking of the opening to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, when Marlow, looking out over the Thames at the start, says,

'I was thinking of very old times, when the Romans first came here, nineteen hundred years ago--the other day. . . . Light came out of this river since--you say Knights? Yes; but it is like a running blaze on a plain, like a flash of lightning in the clouds. We live in the flicker--may it last as long as the old earth keeps rolling! But darkness was here yesterday.’

And darkness there is in Deliverance. Civilisation is a fragile thing. As D. H. Lawrence noted, ‘the American landscape has never been at one with the white man,’ and there are ominous hints at the violence to come. Showing the men the departure point on the map, Lewis ‘marked out a small strong X in a place where some of the green bled away.’

It starts with a tense stopover at the garage owned by the hulking Griner brothers:

They were like two pro football linemen in their first season after retirement when they are beginning to soften up, working as night watchmen. We didn't try to introduce ourselves; the thought of asking them to shake hands with us never occurred to me until years later. I still wonder what would have happened if we had tried.

Conflict simmers. Even the smaller one is ‘twenty pounds heavier than Lewis’. Like the mythical threshold guardian, he warns Lewis that he’s not welcome. Talking about the planned trip, they ‘battled in midair; the sound of crickets in the grass around the garage clashed like shields and armor plate.’ The environment itself harbours hostility.

Griner’s sobre realism (he’s got nothing to prove) makes Lewis’s machismo seem affected. Yes, ‘it’s there,' but Griner warns that, ‘if you git in there and can't get out, you're goin' to wish it wudn’t’. As Griner sees it, 'there ain't nothing to go down there for'. The mountain men, living closer to nature — hideous and desolate, as Bradford put it — don’t harbour the city boys’ fantasies about it.

Lewis, however, as Ed notes, ‘wanted to be immortal. He had everything that life could give, and he couldn't make it work. And he couldn't bear to give it up or see age take it away from him, either…And yet he was also the first to take a chance, as though the burden of his own laborious immortality were too heavy to bear.’ Griner, by contrast, doesn’t need to dance with death like this. He’s ‘never been’ hunting, and ‘the fishing’s no good’ down there either.

Ed ‘wanted to back out; just go back to town and forget it. I hated what we were doing.’ His chest feels ‘hollow,’ and his heart is ‘ringing like iron.’ He senses Lewis’s nihilism. Although the Griners agree to drive the group’s two cars to the end of kayak route for a fee, Ed notes it was ‘hard to believe’ they weren’t ‘saying something mean’.

Yet they don’t turn back. Fantasy prevails. 'I caught a glimpse of myself in the rear window. I was light green, a tall forest man, an explorer, guerrilla, hunter. I liked the idea and the image, I must say.' Deliverance attacks this Romantic vision of Rousseau’s noble savage — the wilderness as a New Eden.

Ed has doubts but ultimately still sees the trip as an escape from emasculation:

‘even if this was just a game, a charade, I had let myself in for it, and I was here in the woods, where such people as I had got myself up as were supposed to be. Something or other was being made good. I touched the knife hilt at my side, and remembered that all men were once boys.’

At the end of the first day, Drew plays his guitar as darkness falls:

I sat up, and the water, though it still swarmed weightlessly with the cave-images of fire, now seemed on the point of swirling them down.

Drew tuned softly, then raked out a soft chord that flowed and floated away.

'I've always wanted to do this,' he said. 'Only I didn't know it.'

He moved up the neck, drawing out chord after chord. These built and shimmered on each other in the darkness, in lonely harmony. Then he began to pick individual notes, and put the bass under them.

'It's woods music,' he said. 'Don't you think so?'

Drew’s last name, Ballinger, hints at balance, and this is an image of Orpheus — music as order and harmony — attempting to tame the wilderness. Ominously, however, it’s a ‘lonely harmony’.

The transition to the second day is in fact a nightmare. Ed recalls the girl he’d photographed at work before leaving, when the ‘bright hardship of the lights’ made him think of those

films you see at fraternity parties and in officers' clubs where you realize with terror that when the girl drops the towel the camera is not going to drop with it discreetly, as in old Hollywood films, following the bare feet until they hide behind a screen, but is going to stay and when the towel falls, move in; that it is going to destroy someone's womanhood by raping her secrecy; that there is going to be nothing left.

With the woods ‘unimaginably dense and dark’ around him, his mind merges his sexual memory of his wife ‘Martha's back heaving and working and dissolving into the studio’ where the same girl, in underwear, is now being photographed with a kitten:

panties stretched, the cat pulled, trying to get its claws out of the artificial silk, and then all at once leapt and clawed the girl's buttocks. She screamed, the room erupted with panic, she slung the cat round and round, a little orange concretion of pure horror, still hanging by one paw from the girl's panties, pulling them down, clawing and spitting in the middle of the air, raking the girl's buttocks and her leg-backs. I was paralyzed. Nobody moved to do anything. The girl screamed and cavorted, reaching behind her.

Sex and blood mingle. And then he feels ‘something hit the top of the tent’ — an owl. Its claw pierces the canvas, and Ed reaches up to touch it:

‘All night the owl kept coming back to hunt from the top of the tent. I not only saw his feet when he came to us; I imagined what he was doing while he was gone, floating through the trees, seeing everything. I hunted with him as well as I could, there in my weightlessness. The woods burned in my head. Toward morning I could reach up and touch the claw without turning on the light.’

The kitten’s claws have become the owl’s talons, and to ‘touch the claw’ is to touch death since owls kill with their talons, not their beaks. In the Egyptian system of hieroglyphics, the owl symbolises death, night, cold and passivity. It relates to the realm of the dead sun — the sun set below the horizon and crossing the sea of darkness.

Ted Hughes’s poem ‘Pike’ ends with the speaker, so terrified of the immense, ancient pike in the depths of the lake that he’s too scared to cast, hearing

Owls hushing the floating woods

Frail on my ear against the dream

Darkness beneath night’s darkness had freed,

That rose slowly towards me, watching.

‘We could have been watched from anywhere,' Ed says thinking about the darkness of the woods. And it is this ‘darkness beneath night’s darkness’ — the infernal, chthonic darkness — that ‘the dream’ of the wilderness frees in Deliverance, too. It rises slowly not only towards them but also within them.

September 15: Descent

‘The woods burned in my head,' Ed remarked. And Dickey said that the action sequences on the river in Deliverance were suggested by the voyage of Satan through Chaos in Milton’s Paradise Lost. In that ‘hoarie deep, / a dark Illimitable Ocean without bound,’ Milton says ‘time and place are lost’. It is the ‘wilde Abyss’ and ‘the Womb of nature and perhaps her Grave’. This recalls the language used of the New World wilderness, and Satan himself —‘wandring this darksome desert’ — is also in search of a frontier, ‘the neerest coast of darness / Bordering on light’.

But whereas Satan has left Hell to search for Eden, the men are going the opposite direction. 'Let's get the hell out of here,' Bobby soon remarks. And Ed, joking about Lewis, says, ‘Tarzan speak with forked tongue…I think we never get out of woods. He bring us here to stay and found kingdom.’ Bobby agrees: ‘Kingdom of Snakes is right’.

Freud saw civilisation as a conflict between eros (love) and thanatos (death). The impulse towards dissolution and death grips Ed as he first enters the river: ‘I was tired of human efforts of all kinds, especially my own,' he says, and could have ‘gone on downstream either dead or alive, to wherever it would take me.’ This is what Keats, in ‘Ode to a Nightingale,' called the urge to ‘fade away into the forest dim,' to ‘cease upon the midnight with no pain’.

The woods, Ed notes, are so ‘dark and heavy’ that ‘the packed greenness seemed to suck the breath out of your lungs,’ and he complains the fog is ‘eating me alive’. He is also figuratively buried alive as he hunts. And he’s hunted. When Ed and Bobby are separated from Lewis and Drew briefly, two men appear:

The shorter one was older, with big white eyes and a half-white stubble that grew in whorls on his cheeks. His face seemed to spin in many directions. He had on overalls, and his stomach looked like it was falling through them. The other was lean and tall, and peered as though out of a cave or some dim simple place far back in his yellow-tinged eyeballs.

The imagery of ‘a cave or some dim simple place’ recalls Lewis’s desire to escape civilisation. These men are red in tooth and claw. Before them, Ed says, ‘I shook my head in a complete void.’ The lean man touches Bobby's arm ‘with strange delicacy.’ Ed is then tied to a tree: ‘it occurred to me that they must have done this before; it was not a technique they would just have thought of for the occasion.’ There is a routine ruthlessness to it. ‘I had never felt such brutality and carelessness of touch, or such disregard for another person's body.’

While Ed is trying to get his breath in ‘a gray void full of leaves,’ Bobby is forced to strip at gunpoint ‘like a boy undressing for the first time in a gym.’ The shorter, older man rapes him. ‘There was no need to justify or rationalize anything; they were going to do what they wanted to. I struggled for life in the air, and Bobby's body was still and pink in an obscene posture that no one could help. The tall man restored the gun to Bobby's head, and the other one knelt behind him.’

Ed hears Bobby’s scream of ‘pain and outrage,’ followed by ‘one of simple and wordless pain.’ At the start of the novel, Ed described Bobby as ‘a pleasant surface human being, though I had heard him blow up at a party once and hadn't forgotten it. I still don't know what the cause was, but his face changed in a dreadful way, like the rage of a weak king. But that was only once.’ Porcine Bobby — the ‘born salesman’ and ‘good dinner or party guest,’ who lives by selling out — now rages again.

Lewis’s words to Ed on entering the woods now reverberate: ‘I admire it, and I admire the men that it makes, and that make it, and if you don't, why, fuck you.’ Just before he left the city, Ed was looking for a 'decent ass' in a crowd of 'horned' women.

Bobby is the ass now.

In the woods, male sexuality is unleashed from the restraining power of women. Bobby in his underwear recalls the girl in hers, and her bloody buttocks (scratched by the kitten in Ed’s vision) foreshadowed Bobby’s.

In The Once and Future King, the Wart —transformed into a fish by Merlin — is taken to see Black Peter, ‘the King of the Moat’ so he can ‘see what it is to be king’. Black Peter, an enormous fish, is ‘remorseless, disillusioned, logical, predatory, fierce, pitiless’. And his words to the Wart sounds like the kind of thing Lewis would say:

'Love is a trick played on us by the forces of evolution. Pleasure is the bait laid down by the same. There is only power. Power is of the individual mind, but the mind's power is not enough. Power of the body decides everything in the end, and only Might is Right.'

‘The body,’ as Lewis said, ‘is the one thing you can’t fake.’ And for these men in the woods, ‘power of the body’ knows nothing of love.

Homosexuality is the uncivilised male sex drive. By contrast to Griner — ‘a huge creature, twenty pounds heavier than Lewis, dressed in overall pants and an old-fashioned sleeveless undershirt, with a train engineer's cap on and cutdown army boots’ — the image of Lewis in the water sounds like gay soft porn:

‘Everything he had done for himself for years paid off as he stood there in his tracks, in the water. I could tell by the way he glanced at me; the payoff was in my eyes…You could even see the veins in his gut, and I knew I could not even begin to conceive how many sit-ups and leg-raises -- and how much dieting -- had gone into bringing them into view.’

The description of Griner emphasised his strength: his hand was ‘held…like he was having to keep it down by all the strength in his other hand and the rest of his body.’ Lewis values the way another man looks at him. Tellingly, ‘talk about sex was never something he seemed to enjoy.’

One of the best established findings in anthropology is that homosexuality is always most common in areas with the fewest women (prisons and the navy, for example). And here, in Lewis’s woods fantasy, Dickey, who wrote the screenplay to the 1975 Call of the Wild TV production, presents it as a form of atavistic abuse:

The white-haired man worked steadily on Bobby, every now and then getting a better grip on the ground with his knees. At last he raised his face as though to howl with all his strength into the leaves and the sky, and quivered silently while the man with the gun looked on with an odd mixture of approval and sympathy. The whorl-faced man drew back, drew out.

A whorl is a circle around a point on an axis, and this is the pivot of man to beast. The ‘howl’ recalls Hobbes’s state of nature: man is wolf to man. Lewis, when he first arrived to collect Ed for the trip, was described as having a ‘wolfish face’. And what Janusz Bardach describes in Man is Wolf to Man: Surviving the Gulag is strikingly similar to the men’s descent into Hell in Deliverance:

'[A]n excited group of prisoners gathered around a bench next to the wall. Those in the back row were jumping up, trying to see over the heads and shoulders of those in front, who were shouting obscenities and holding their penises….A young man lay on his stomach [in the baths], and another man lay on top of him, embracing him around the chest and moving his hips back and forth. His back was tattooed with shackles, chains, and the popular Soviet slogan ‘Work is an act of honor, courage, and heroism.’ On both sides were trumpeting angels. He breathed heavily, while the young man underneath moaned and cried out. The spectators shouted. I caught sight of the young man’s grimacing face.'

This is men going their own way. This is the world of Black Peter, where only Might is Right. This is the world of Africa today, where male rape is used in war. Fenrir, the giant wolf in Norse myth who symbolises the destructive potential of evil, breaks his chains at Ragnarok and devours the world. And the wolf within man, unchained, destroys civilisation.

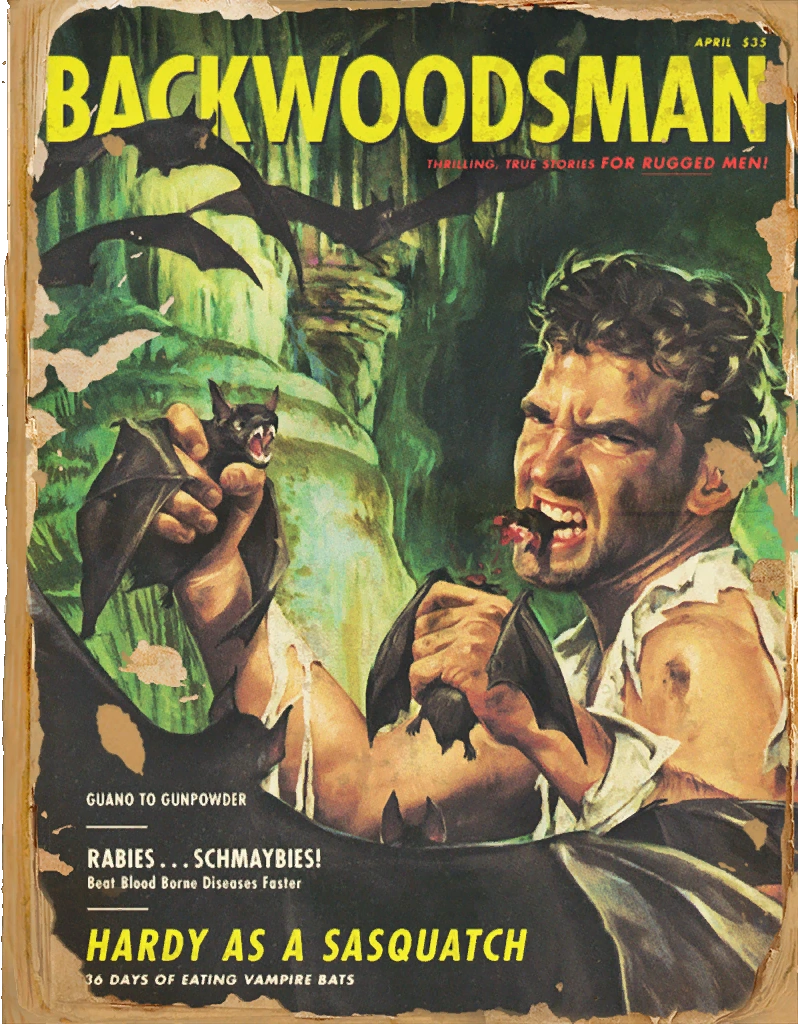

Having finished with Bobby, the rapists turn to Ed, who is ‘blank’ (again, ‘the void’). Bobby was a ‘boy,’ but now Ed is not merely a boy but also a mere animal: 'You’re hairy as a goddamned dog, ain't you?'

'Ain't no hair in his mouth,' the other one said.

He said to me, 'Fall down on your knees and pray, boy. And you better pray good.'

But then as the man unbuttons in front of Ed’s face — in an echo of the rape — ‘a foot and a half of bright red arrow was shoved forward from the middle of his chest’. It’s Lewis. The colour red now connects the two scenes to register the reality of the world of the woods. The man’s ‘lips turned red,’ and ‘he opened his mouth and it was full of blood like an apple.’ Bobby, whose ‘faced expanded its crimson,’ has eyes ‘as red as the bubble in the dead man's mouth’. In an echo of the rapist drawing out of Bobby, ‘the arrow slowly slithered from the body, painted a dark uneven red.’

The other man escapes, leaving them to bury his companion. Ed, in an echo of Dante ‘lost in the middle of a dark wood,’ is left ‘wandering foolishly in the woods holding a corpse by the sleeve’. They finally find the burial place: ‘a sump of some kind’ where there is ‘rotten water’. When Lewis — looking even ‘more functional and accurate than the form of an archer on an urn’ (the hunter motif again) — fires an arrow into it to test the depth, ‘there was no sense of the arrow's being stopped by anything under the water — log or rock. It was gone, and could have been traveling down through muck to the soft center of the earth.’

This is hell. The ground is ‘mulchy like shit,’ and they dig the grave ‘with the collapsible GI shovel we had brought for digging latrines.’ The ‘hollowed out…trench’ echoes the ‘hollow’ feeling in Ed’s chest as Griner warned them not to come here. The place has the ‘smell of generations of mold’ — a symbol of man’s primal past. Thinking about it being covered by the dam, Ed realises ‘they might as well let the water in on it…this stuff is no good to anybody.’ Water can cleanse as well as drown.

Having buried the rapist, they continue down river. ‘The beginning of darkness was thrown over us like a sheet,’ Ed says, evoking a burial shroud. It’s ‘like flying down an underground stream with the ceiling ripped off’. Unlike Lethe, however, the water from this river of hell won’t let them forget. And Drew is soon shot (they believe) by the hillbilly who got away. The musician — his last name, Ballinger, hinting at balance — couldn’t harmonise the chaos. Bobby bends over, but Drew, unable to find what it takes within himself to fight, is broken.

And so is Lewis’s leg, so Ed must now climb a cliff to hunt the shooter. He notes ‘the cliff looked something like a gigantic drive-in movie screen waiting for an epic film to begin,’ recalling Emerson’s definition of America as ‘a poem before our eyes’. On the stage of the landscape Ed must play the role of the hero, writing his story on its pages.

This involves finding his own darkness — doing what Drew had been unable to — and as he wades through the water he feels ‘the depth came into me, increasing -- no one can tell me different - with the darkness.’ The forest, Jung pointed out, is a symbol of the unconscious, and the sylvan terrors of fairy tales — wolves, dragons, witches, ogres — represent its perilous elements. They threaten to devour or obscure reason.

September 16th: Return

During the climb, Ed becomes bestial. He is in touch with nature and 'smelling for blood like an animal' as he pursues Stovall (the rapist). The hunter hero, Slotkin says, experiences 'an initiation and conversion in which he achieves communion with the powers that rule the universe beyond the frontiers and acquires a new moral character … a new identity'. Accordingly, after the climb, Ed lies in a crevice — ‘solid on one side,’ he says, ‘with stone and open to the darkness on the other, as though I were in a sideways grave.’ His old self has to die.

Below him is the ‘river in its icy pit of brightness.’ (The deepest circle of Dante’s Inferno is ice, not fire.) It’s ‘a kind of god,’ he feels, and his experience on the cliff is a kind of transcendence: ‘I had thought so long and hard about him that to this day I still believe I felt, in the moonlight, our minds fuse.’ As Nietzsche warned, ‘he who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.’

Slotkin adds that the hunter-hero’s adventure always culminates in violence since 'the killing of the quarry confirms him in his new and higher character and gives him full possession of the powers of the wilderness.' And Ed finds that in fact the wilderness, as the early settlers feared, nearly takes full possession of him. After accidentally falling on his own arrow, he finds ‘walking was odd and one side-sided’. Like the Inferno’s pilgrim, he now walks with a limp. This is fallen and divided man.

Dickey echoes Bobby’s rape:

The broadhead had torn my side open…it was in me. In me. The flesh around the metal moved pitifully, like a mouth, when I moved the shaft. I put the knife against the flesh above the wound. Just cut right down, I said aloud. Cut down and cut it loose, and you'll be able to clean the wound out in the river. It will be a lot better that way, boy.

Ed’s mouth escaped violation early thanks to Lewis, but now his flesh is penetrated instead. Like Bobby, he’s a ‘boy’. But the real danger comes when, having killed Stovall, he feels overcome by the call of the wild:

I took the knife in my fist. What? Anything. This, also, is not going to be seen. It is not ever going to be known; you can do what you want to; nothing is too terrible. I can cut off the genitals he was going to use on me. Or I can cut off his head, looking straight into his open eyes. Or I can eat him. I can do anything I have a wish to do, and I waited carefully for some wish to come; I would do what it said.

Thus ‘the ultimate horror’ circles him. It ‘played over the knife.’ He manages to evade it — echoing, perhaps, the Orphic musician Drew — by singing ‘a folk-rock tune,’ but the image is one of possession, a rape of the spirit: 'I finished, and I was withdrawn from. I straightened as well as I could. There he is, I said to him.' Only Christ entered Hell without Hell entering Him.

With Stovall dead, Ed descends the cliff but falls into the river on the way down:

…the river went into my right ear like an ice pick. I yelled, a tremendous, walled-in yell, and then I felt the current thread through me, first through my head from one ear and out the other and then complicatedly through my body, up my rectum and out my mouth and also in at the side where I was hurt.

It is another image of violation, and the ‘walled-in yell’ anticipates the primal scream the men give shortly as, returning to life after their descent into the darkness, they go down a waterfall. Lewis, with the compound fracture in his thigh, ‘looked like some great broken thing’. The wilderness has humbled his pride. Griner was right.

Approaching the falls, Ed says he ‘got ready to die again’. He closed his eyes and ‘screamed with Lewis, mixing my voice with his bestial scream, blasting my lungs out where we hung six feet over the river for an instant and then began to fall.’ After the fall, taking them six feet deep, Lewis says, ‘I want to get out of my own coffin, this fucking piece of tin junk.’ And when they finally exit the woods, they find a doctor with the 'hands of an angel.'

After: Deliverance

After changing his clothes, Ed says, ‘a shave would have made me a completely new person, but I was half-new anyway, and half-new was very good; it is better to come back easily.’ But difficulties still remain. The wife of one of the dead rapists has told the Deputy Sheriff he’s missing, so there’s a search for the body. ‘We've been through a goddamned bad time,’ Ed tells him, continuing the damnation theme, and he manages to hide the truth even though the Deputy doesn’t believe him:

'He's lyin'. Sheriff, don't let him go. Don't let the son of a bitch go.'

'We got nothing to hold him for, Arthel,' the sheriff said. 'Nothing. These boys've been through a lot. They want to get back home.'

He then sleeps ‘in a place beyond all sleep, around on the other side of death,' and he says

'The river and everything I remembered about it became a possession to me, a personal, private possession, as nothing else in my life ever had. Now it ran nowhere but in my head, but there it ran as though immortally. I could feel it -- I can feel it -- on different places on my body. It pleases me in some curious way that the river does not exist, and that I have it. In me it still is, and will be until I die, green, rocky, deep, fast, slow, and beautiful beyond reality. I had a friend there who in a way had died for me, and my enemy was there.'

Ultimately, he never leaves the river because it never leaves him. And the water doesn’t wash away the lie in his soul or bring Drew back. 'Drew was the best man we had,' he tells Drew’s wife. 'I'm so sorry. I'm so goddamned sorry.' Mrs. Ballinger simply replies, 'You can get out of here and go find that insane friend of yours, Lewis Medlock, and you can shoot him.'

Ed, chastened, no longer lusts after the ‘gold-halved eye’ of the underwear model that, at the start of the novel, he’d seen shining ‘in the center of Martha's heaving and expertly working back’ as they had sex. Now it has ‘lost its fascination,’ whereas before it had ‘promised other things, another life, deliverance’.

Instead, Ed realises that Martha is what he has ‘undervalued’. When he first arrives home, she removes his shirt and looks at the arrowhead wound ‘with pure, practical love,’ and she steadies him while he waits, terrified, by the window because he thinks the police are coming for him:

Back at home I put an easy chair in front of the picture window and got a blanket and a pillow and sat looking out onto the street with the phone beside me all afternoon. I was shaking. Martha sat on the floor and put her head in my lap and held my hand, and then went and got a bottle of whiskey and a couple of glasses.

Odysseus’s goal was to get home to Penelope, and the true hero’s adventure starts as he steps into his own front door.

As for Lewis, who had more than a touch of Achilles about him, 'he can die now; he knows that dying is better than immortality,' Ed says. Limping from his injured leg, he stills like to shoot, and his final words in the novel are telling: 'I think my release is passing over into Zen…Those gooks are right. You shouldn't fight it. Better to cooperate with it. Then it'll take you there; take the arrow there.'

Hopefully this essay takes you to the novel.

I was only ever taught one prayer in my time in the military. "Yay though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I shall fear no evil. For I am the baddest motherfker in the valley."

Could have been Lewis' motto. It's certainly mine.