‘All civilisations, at least in their early stages, are based on success in war,’ wrote Kenneth Clarke in Civilisation. And success in war is based partly on the traits now termed toxic masculinity by the American Psychological Association: aggression, competitiveness, dominance and stoicism. Accordingly, such traits are celebrated in the heroes of literature that has stood the test of time: the bards didn’t sing of cowards or pacifists.

The Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf embodies what the historian Norman Cohn has termed this ‘conflict myth’ of civilisation’s origin. The epic hero in early Old World cultures - from Egypt to the pagan Norse - represents harmony, order and nationhood. And the entire social system (supported by religion) rests on a man vs. monster allegorical origin myth. Only after the hero confronts the chaos that threatens order can civilisation flourish.

Like the Homeric epics of the 8th century BC, Beowulf was composed without the aid of writing - chanted or recited to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument and transmitted orally from bard to bard over generations, written on the wind and the heart. Unlike them, however, all its central battles pit its hero against not men but monsters - enemies of not just the community but civilisation itself.

The linguist Noam Chomsky showed that all human languages share basic structural similarities, and all stories do as well. Conflict is at their core. The hero confronts trouble and must overcome it, often being transformed in the process. Man, as the novelist Walker Percy put it, is a ‘creature in trouble, seeking to get out of it, and accordingly on the move’, and fellow novelist John Gardner described stories as ‘vivid and continuous dreams’ - attempts to order the chaos of experience.

Probably composed around 700-750AD and surviving in a single manuscript that scholars date to the early 11th century, Beowulf is the masterpiece of Old English literature and the earliest European vernacular epic. Set in pre-Christian northern Europe in the early 6th century and based on subject matter taken from German legend and history, it celebrates the Germanic - more broadly the heroic - code of loyalty, valour and honour.

As Tolkien noted, its fundamental theme is the conflict between order and chaos. The action opens in medias res (in the middle of things) in Denmark, where King Hrothgar’s mead hall, Heorot, has been attacked for 12 years by the monster Grendel. Heorot symbolises order: inside it, the bard sings about the ordering of chaos. And the sound of this music enrages Grendel, just as Satan can’t stand the sight of Adam and Eve’s happiness in Eden in Milton’s Paradise Lost.

In common with other monsters, Grendel comes from a realm of night and water - primordial symbols of chaos - to defeat and devour Hrothgrar’s warriors. Monsters and civilisation are in fact coeval: they arose together in early dynastic Egypt and Mesopotamia in 3000BC. Civilisation depends on a threshold, and monsters embody the forces that threaten it: Grendel is described as a ‘boundary walker’. And the hero’s duty is to defend the boundary without which civilisation falls.

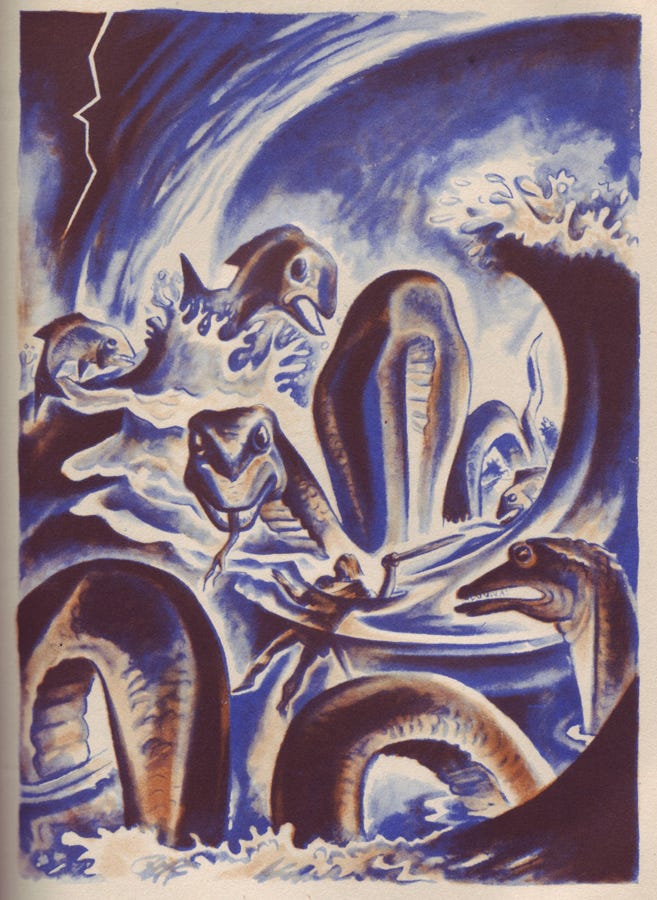

So Beowulf, a prince of the Geats of southern Sweden, arrives with a small band of retainers and offers to rid Heorot of its monster. Hrothgar welcomes Beowulf, but a Dane named Unferth scorns Beowulf’s tale of defeating another warrior called Breca in a swimming race at sea while killing sea monsters. Unferth doesn’t understand it’s not really about Beowulf vs. Breca but man vs. sea. Beowulf is victorious over Breca because he is the better conqueror of chaos.

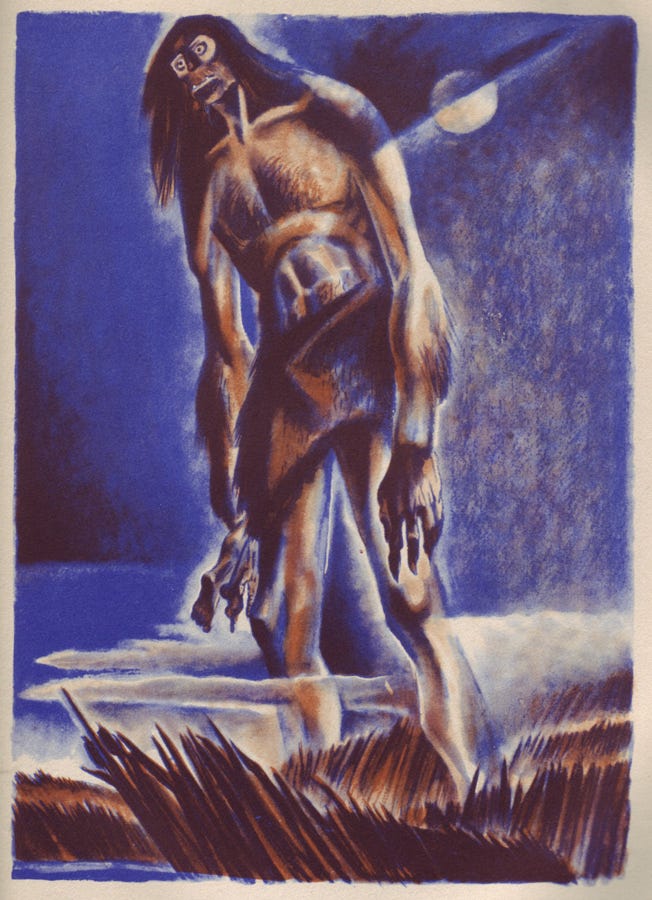

And so when Grendel comes from the moors at night, tears open Heorot’s heavy doors and devours one of the sleeping Geats, Beowulf grapples with him. Having shunned weapons and armour, Beowulf rips off Grendel’s arm as - terrified of Beowulf’s strength - he tries to escape, leaving him mortally wounded. So the encounter shows that Beowulf and Grendel are similar in their size, strength, bravery and willingness to dismember their opponents.

This ‘reshuffled familiarity’ of monsters, as Harpham termed it, means they threaten not just physical but cognitive boundaries; they confuse cultural categories. Dracula and Frankenstein resemble us, and Micronesian and Polynesian mythologies feature were-sharks and were-octopuses. Mutant and atavistic, Grendel is called not just ‘boundary walker’ but ‘shadow walker’, and ‘The Shadow’ is the name Jung gave to the dark side of the personal unconscious.

And just as Grendel symbolises the potentially destructive element within Beowulf, Grendel’s mother is the demonic complement to Hrothgar’s Queen, Wealtheow. The day after Grendel’s death, Heorot rejoices, but at night Grendel’s mother comes to avenge her son by killing one of Hrothgar’s men.

Seeking vengeance, Beowulf journeys to her haunted mere, whose surface resembles a stormy sea, the antithesis of Heorot - chaos and darkness vs. order and light. A hart links Heorot and the mere: it seems to have chosen the place where Heorot was built, but it chooses death from the hounds pursuing it rather than enter the mere’s haunted waters. The opposite of the amniotic waters of the womb, these waters - teeming with serpents - are death.

And when Beowulf dives down to face Grendel’s mother in her cave, during the fight she sits on top of him. As Jung observed, it is a universal peculiarity of lamia - the devouring mother figures of mythology - that they ride their victims. Before the battle, Beowulf’s own mother is mentioned for the first time, reminding us he is mortal and juxtaposing her to Grendel’s mother. And Beowulf now arms himself because he is invading the monstrous world, not fighting within the limits of human control as he was in Heorot against Grendel.

His acceptance of the fratricide Unferth’s sword also shows his acceptance of his role in a heroic society that mingles order and violence. When fighting Grendel, Beowulf didn’t owe Hrothgar anything: he was magnanimously defending mankind from monsters. But he is now enmeshed in a feud. Beowulf took Grendel’s arm and shoulder, so Grendel’s mother took Aeschere, Hrothgar’s ‘shoulder companion’, and now Beowulf is obliged to kill her.

But Unferth’s sword shatters when Beowulf uses it: he transcends the flaws of the system it stands for. Beowulf is only saved by his magical armour and by an ancient, giant sword he finds in her lair, with which he kills Grendel’s mother and decapitates Grendel. This sword then dissolves to the hilt, becoming as useless against men as Unferth’s was against monsters. Writing centuries after the action, the Christian poet stresses that the hero is in but not of the pagan world.

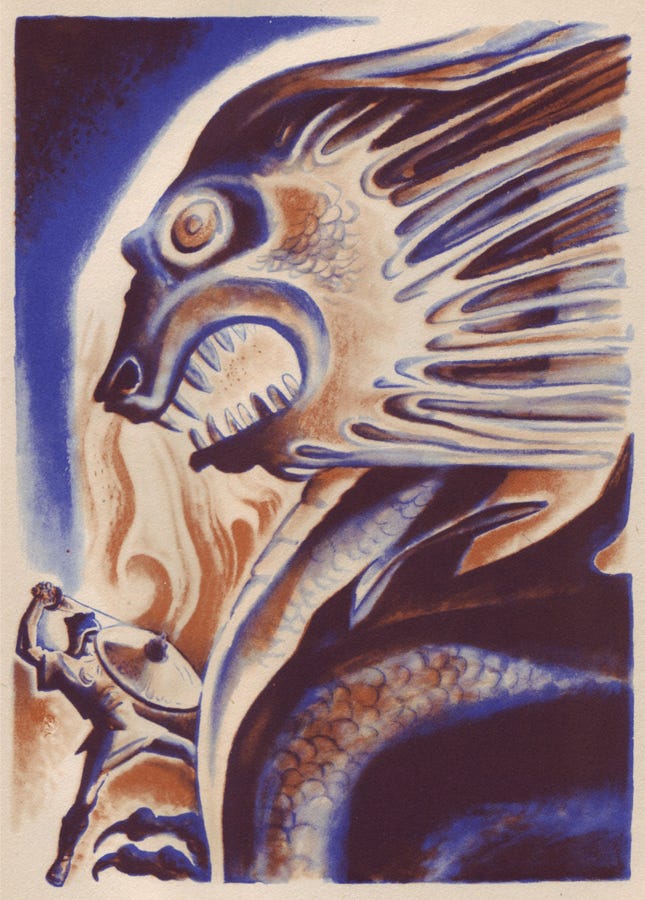

With the mere-hag’s 50-year reign ended and Heorot is liberated, Beowulf enjoys a peaceful rule of 50 years as king of the Geats, putting his strength and prowess in service of defending the kingdom against its human enemies. But as order is always fragile, then comes Beowulf’s final battle: a dragon, the supreme symbol of chaos. To its lair he again brings arms and armour, symbols of the heroic system and of the limits of human power. He regrets their necessity. But this is his duty.

And as in the mere, his victory depends on an unusual weapon - an enormous iron shield that covers both him and Wiglaf, the only one of his men not to abandon him in terror. After Beowulf shatters his sword (just as he did against Grendel’s mother), Wiglaf uses his own to defend him. Inherited from Wiglaf’s father, who was loyal to his lord, it symbolises the values of the heroic society that obliges Beowulf to face the dragon.

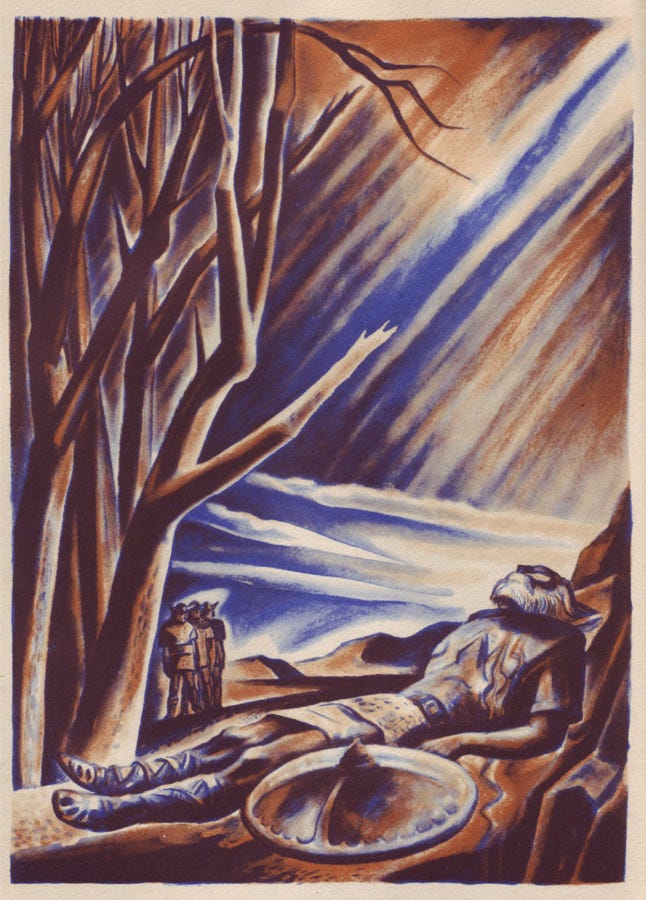

Beowulf kills the dragon but is mortally wounded, so the poem ends with a mixed view of heroism. Is the ideal attainable? Tested by fire, all but one of the best men handpicked by Beowulf fled. And Beowulf’s dying vision of his reputation living on and the heroic values enduring is darkened by his knowledge that only one of his clan survives. Despite leaving his armour and greatest treasure to Wiglaf, he is buried alongside the ‘last survivor’, who left everything to the grave.

This nameless figure from a forgotten past offers a bleak vision of futility. No human civilisation can ultimately endure. As the critic George Clark observes, ‘the poem sees essential nature as hostile to mankind: water engulfs, fire consumes, and earth corrodes the prizes of heroic life’. And so in Beowulf’s funeral pyre even the arms and armour burn along with his body. A haunting image in Old English poetry describes the life of man as bird that enters the bright banquet hall from the darkness outside, briefly dances in the light, then flies into darkness again.

Pascal put it this way: the final act is tragic, no matter how fine the rest of the play. But even the elements seem to acknowledge Beowulf’s nobility. The wind calms, and the smoke of the fire drifts straight up to heaven. And although the Christian poet, writing centuries after the action is set, doubts whether the heroic values are sufficient, the Geats mourning Beowulf do not doubt they are necessary. Without Beowulf’s protection, they will no longer be able to withstand their enemies.

And without Charles Martel’s victory over the Moors at Poitiers in 732, around the time Beowulf was composed, western civilisation might never have existed. Without the heroic virtues, no higher virtues are possible. Without the blood shed by the warrior, the bard has no safe space in which to sing his song.

By blood we live, the hot, the cold

To ravage and redeem the world:

There is no bloodless myth will hold.

- Geoffrey Hill, ‘Genesis’.

Wiglaf also chastises the nobles who served with Beowulf, but did not come to his aid. The society is thrown into doubt now that their greatest hero has fallen.

The spear must be seized, morning-cold,

hefted in hand, on many dark dawns;

no harp music will wake the warriors,

but the black raven above doomed men

shall tell the eagle how he fared at meat

when with the wolf he stripped the bodies.

Each generation must rise and face the chaos of the world or be consumed by it.

Wiglaf also chastises the nobles who served with Beowulf, but did not come to his aid. The society is thrown into doubt now that their greatest hero has fallen.

The spear must be seized, morning-cold,

hefted in hand, on many dark dawns;

no harp music will wake the warriors,

but the black raven above doomed men

shall tell the eagle how he fared at meat

when with the wolf he stripped the bodies.

Each generation must rise and face the chaos of the world or be consumed by it.