Advertising and social media assault your mind with thirst traps. You should watch what you put in it more carefully. So here are ten paintings for manly meditation.

Botticelli, Pallas and Centaur, c.1482

Pallas, Goddess of Wisdom, triumphs over man’s animality, represented by the centaur. This must happen within every man. But Wisdom is a woman because this process also happens between men and women. Civilisation is only possible when women civilise men. Through the family, men are integrated into the community. Community otherwise descends into animality. Beauty and the Beast is a variation on this theme.

Piero di Cosimo, Venus and Mars, 1498

In the love affair between the Goddess of Love and the God of War, she vanquishes him. Sleeping Mars is not just a physiological allusion to how men usually fall asleep soon after sex. He also symbolises how love defeats strength: Venus, by contrast, stays pensively awake, and the rabbit gnawing at her loins is a reminder of her niggling sexual frustration.

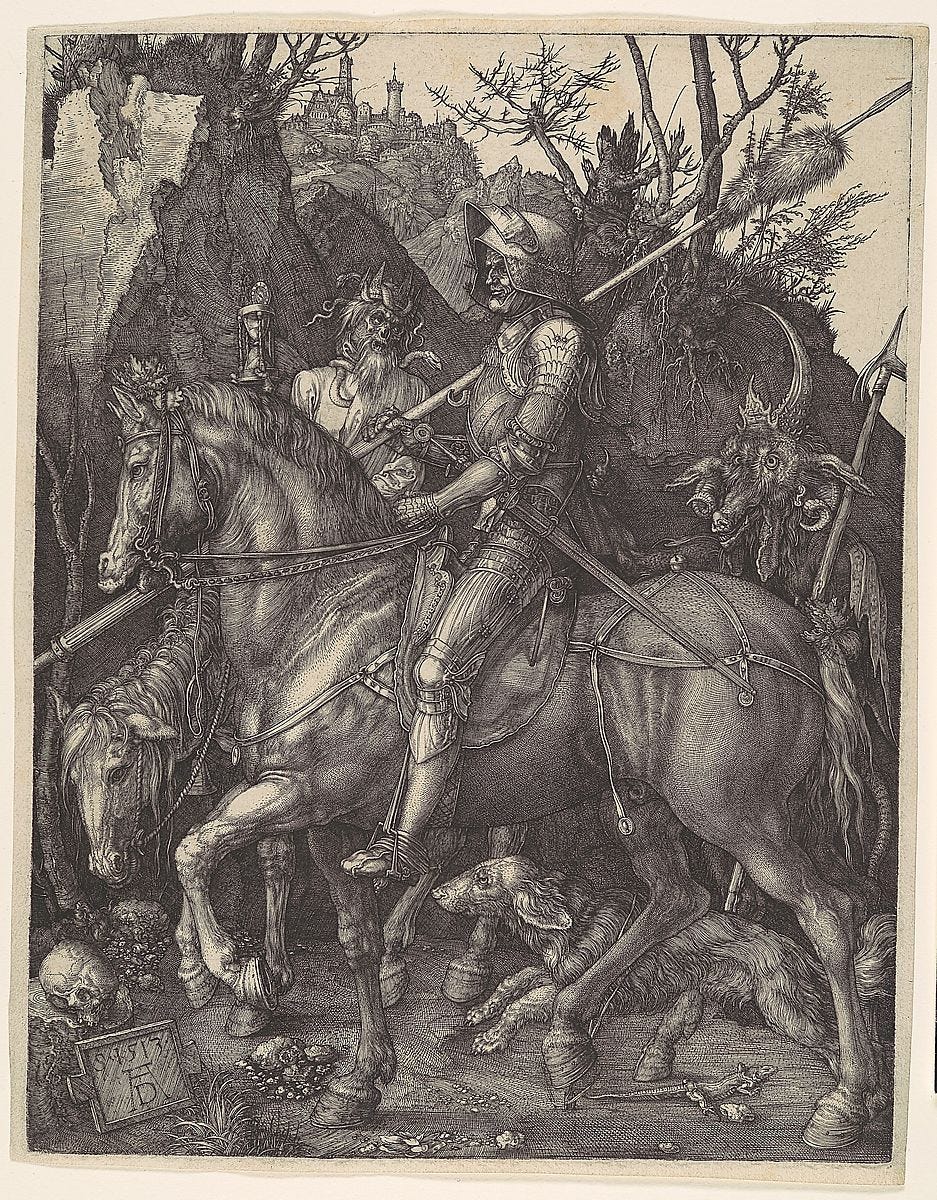

Dürer, Rider (1513)

This embodies the state of moral virtue outlined in Erasmus's 'Instructions for the Christian Soldier', published in 1504:

"In order that you may not be deterred from the path of virtue because it seems rough and dreary ... and because you must constantly fight three unfair enemies—the flesh, the devil, and the world—this third rule shall be proposed to you: all of those spooks and phantoms which come upon you as if you were in the very gorges of Hades must be deemed for naught after the example of Virgil's Aeneas ... Look not behind thee."

Death on a Pale Horse holds out an hourglass as a reminder of life's brevity, and a pig-snouted Devil lurks nearby: 'Sin lieth at the door. And unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him.' Yet the rider is undistracted, his expression contemptuous. As it is written, 'Act like a man, and take courage, and do: fear not, and be not dismayed.' (1 Chronicles 28:20)

Spranger, Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, c.1590

The nymphomaniac naiad Salmacis, who chose vanity and idleness rather than following the virginal Greek goddess Artemis, is spellbound by the beauty of the naked Hermaphroditus. In a masterful portrayal of the power of female sexuality, her body is coiled like a predator’s ready to pounce as, removing her garments, she prepares to flick off her shoe. He spurns her, but she won’t relent, and disaster follows for them both.

Carracci, Hercules at the Crossroads, c.1596

Hercules sits at the centre of the crossroads symbolising two ways of life. On his right, Pleasure, suggestively physical, tempts him with playing cards, musical instruments, and theatrical masks. The landscape is inviting — verdant, fertile, lush. But on his left, Virtue gestures to Hercules’s winged horse, Pegasus. The horse, mastered by its rider, is a symbol of man’s triumph over his baser nature (as in Plato’s allegory of the chariot). The road is hard; the landscape, forbidding. But the laurels on the poet in the bottom left remind Hercules that Virtue will bring renown.

Cavalier d’Arpino, Rape of Europa, 1607-8

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Jupiter assumes the form of a bull and seduces Europa. She climbs on its back willingly, holds its horn and, with her breasts exposed, drapes her hand over its muscles. Seduction and rape are basically synonymous in Greek myth, especially where Zeus/Jupiter is concerned: ‘rapture’ and ‘rape’ are even etymologically related. From this union came the birth of Minos, king of Crete and the Minoans — the first European civilisation. Sex is the core of culture, and in Mithraic ritual, the sacrifice of the bull symbolised the penetration of the feminine principle (the fertile soil) by the masculine (the blood of the bull).

Saraceni, The Fall of Icarus, 1608

The famous architect Daedalus wanted to leave the island of Crete, but the sea stopped him, so he invented wings using feather and wax. In spite of his father’s warning, his son flew too close to the sun. This well-known story from Ovid symbolises how pride comes before a fall. But Icarus is an allegory of not only impiety (sons should heed their fathers) but also how over-confident cultures ignore the wisdom of their ancestors. This is a painting for our time in both senses. Saraceni emphasises the enormity of nature to show its triumph over man’s technology, and the Enlightenment project of power over nature also aims at power over human nature itself.

Rubens, Angelica and The Hermit, 1620-25

In Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, Angelica — one of the most sought-after women in the story — spurns all her would-be lovers, causing Orlando’s madness. After two soldiers fight over her, she runs away and seeks refuge with an old hermit. Thinking he’s venerable, she imagines she’s safe. But he instantly gets an erection and, using spells, puts her into an enchanted sleep. Unusually but profoundly, Rubens shows him voyeuristically gazing at her. No power on earth compares to hers. Fertile young women are the real enchanters.

Carle van Loo, Aeneas Carrying Anchises, 1729

The embodiment of Roman virtue, Aeneas carries his elderly father Anchises from burning Troy. With them are Creusa and Ascanius, his wife and son. She confides the Penates or household gods to the old man, symbolising the continuity of the race; she herself, however, will soon be lost in the flames. Returning to search for her, Aeneas, in desperation, will find only her ghost. Gazing back at the blaze, the little boy feels the fragility of order, its vulnerability to violence — what seemed so solid is reduced to smoke.

Tiepolo, Rinaldo Abandoning Armida, 1745

Here, in an episode from Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata, the enchantress Armida — having been persuaded by the Saracens — has seduced the Christian soldier, Rinaldo. But she has fallen truly in love with him. Rinaldo’s fellow soldiers sent to retrieve him make him remember — as he looks back at her open arms and legs — his Christian duty, and he leaves her heartbroken.

In the Odyssey, Calypso similarly ensnares Odysseus. A sex-starved nymph, she keeps him on her island for seven years. Her name comes from the Greek kalyptein, which means to cover or conceal. Odysseus later understands her embraces were to “banish from my breast my country’s love.” When he breaks free, it's an apocalypse - literally, an uncovering or unveiling. Calypso had cloaked his destiny with carnality.

Which is your favourite and why? Comment below…

Carracci, Hercules at the Crossroads. The first thing I noticed is that the arts equated to the perils of lust. I am warned that my aim to discover great literature can become a decadent indulgence if it is at the expense of action in the world.

I did not see Pegasus in the distance at first. Unlike on the right of the image, which has the woman illuminated and masks close in the foreground, the eye takes time to travel down the path and has to work to see Pegasus in shadow. A life that is note worthy is not one that is within easy reach.

Durer, Rider. I liked this one the best because of its style and it is always good to be reminded of death. I would like to hang this up in my house. I’m sure it would be a great conversation starter.