Sir John Glubb served in World War One in France and Belgium. Wounded three times, he was awarded the Military Cross. From 1939 to 1956, he commanded the famous Jordan Arab Legion. In his retirement, he lectured on the rise and fall of empires. Military history has suffered more than any other subject from the woke-washing of academia, so my aim here is to help give his findings the attention they deserve.

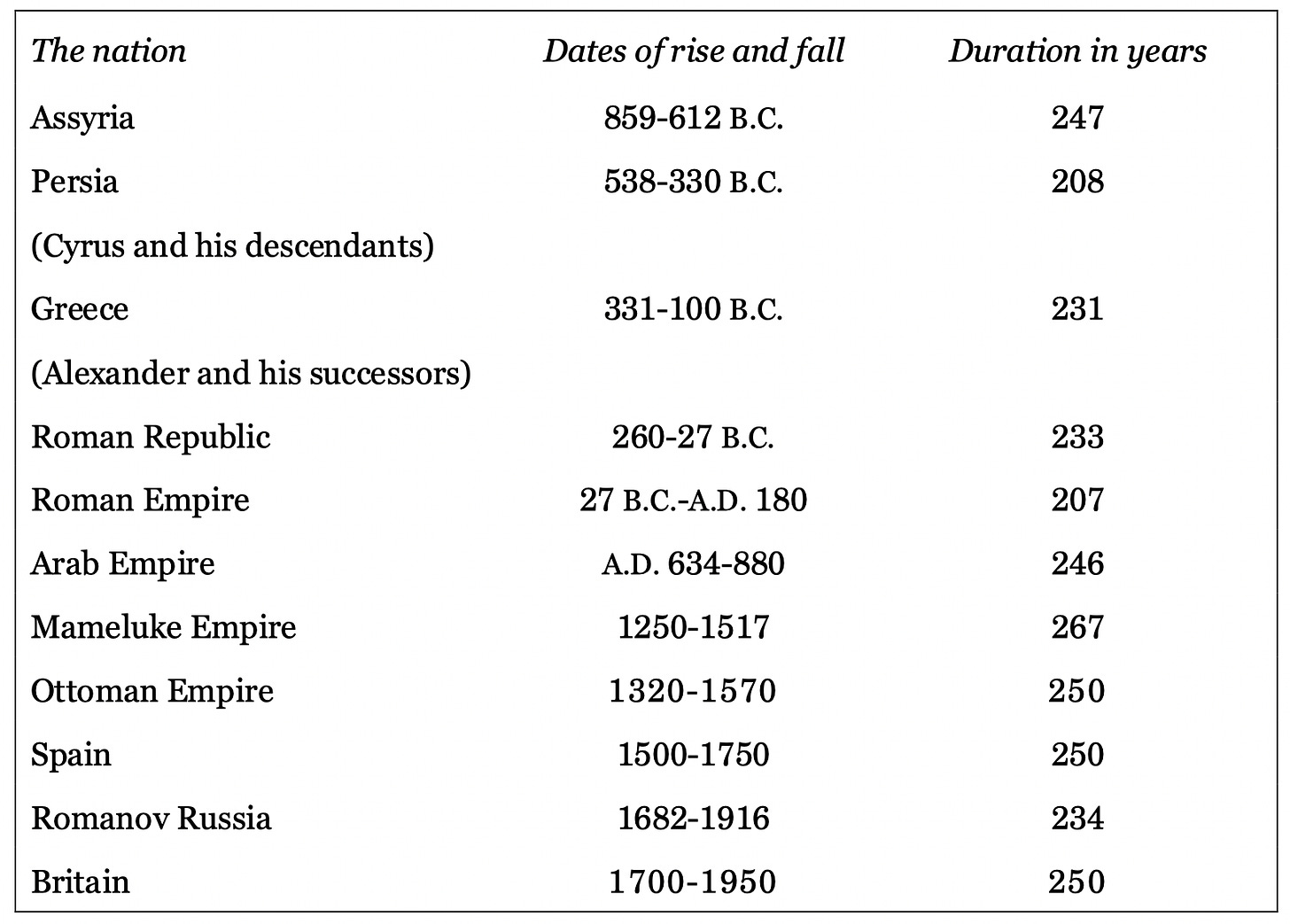

‘We do not learn from history,’ he said, ‘because our studies are brief and prejudiced,’ but surveying the whole means that, ‘in a surprising manner, 250 years emerges as the average length of national greatness.’ Since ‘this average has not varied for 3000 years’, he wondered whether it might ‘represent ten generations.’

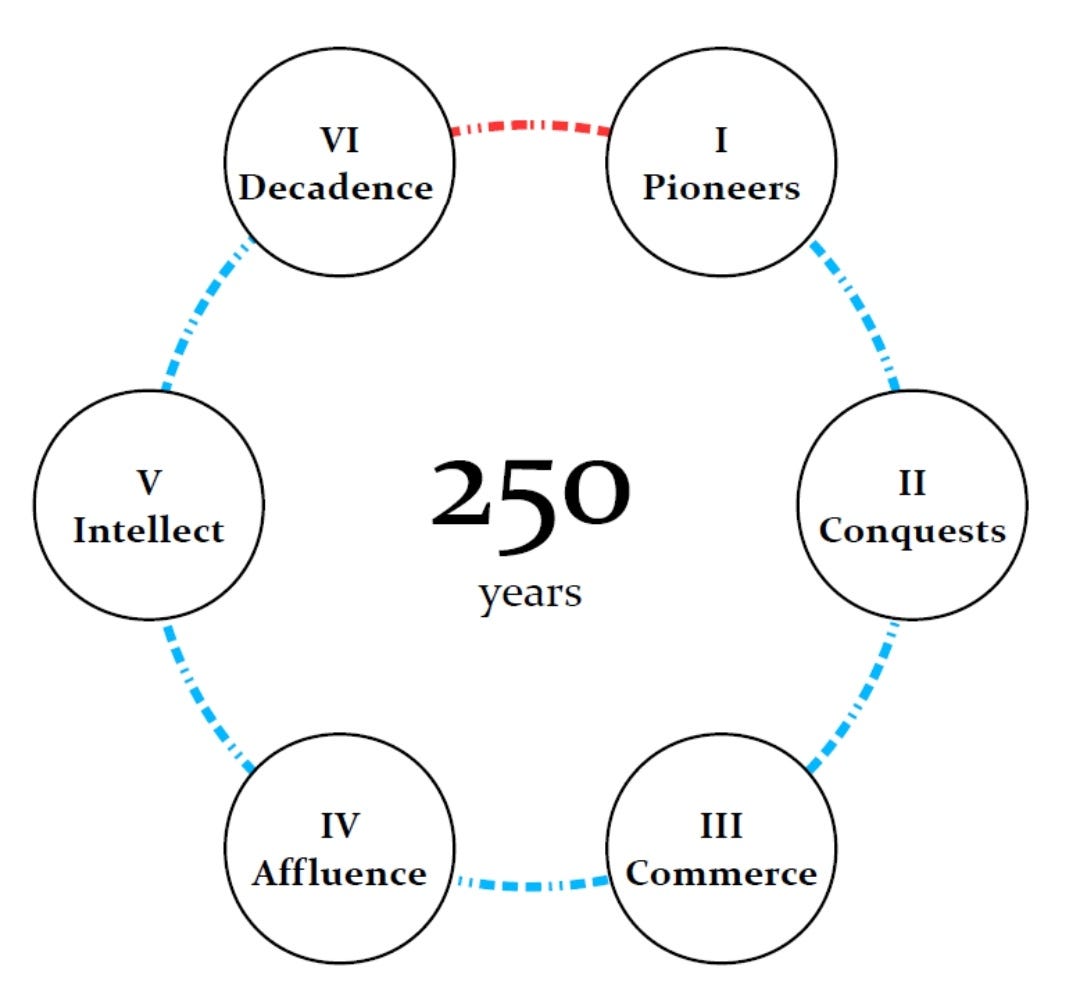

He discerned six stages in the rise and fall of great nations:

Each has distinctive characteristics.

The Age of Pioneers

He noted that ‘again and again in history we find a small nation, treated as insignificant by its contemporaries, suddenly emerging from its homeland and overrunning large areas of the world.’ At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Mongols were remote, savage tribes; by 1253, their empire — one of the largest in the history of the world — extended from Asia Minor to the China sea.

What he called these ‘sudden outbursts’ are characterised by ‘an extraordinary display of energy and courage,’ and he added that ‘the new conquerors are normally poor, hardy and enterprising and above all aggressive.’ By contrast, the ‘decaying empires which they overthrow are wealthy but defensive-minded.’ The Arab warriors who sacked the Byzantine empire were disgusted by the decadent golden cups.

But the conquerors, he added, are ‘not only distinguished by victory in battle, but by unresting enterprise in every field.’ Although ‘poor, hardy, often half-starved and ill-clad,’ they ‘improvise and experiment’ to ‘overcome every obstacle’. Sometimes — as in the case of Atilla and the Huns — their motivation is ‘mere loot, plunder and rape.’ But the barbarians admired Rome and ‘themselves aspired to become Romans.’

He believed that the conquerors could serve to purge the decaying empire by burning it like dead wood. 'Every race on earth,’ he said, ‘has distinctive characteristics. Some have been distinguished in philosophy, some in administration, some in romance, poetry or religion, some in their legal system.’ And the rise and fall of empires allows each to place itself at the service of mankind during its period of pre-eminence.

The Age of Conquests

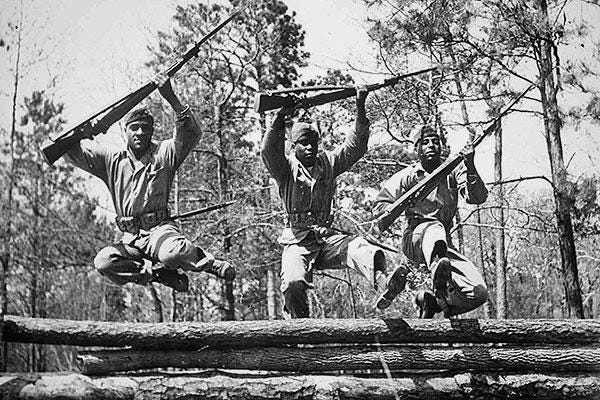

After ‘a little-regarded people suddenly bursts on to the world stage with a wild courage and energy in the Age of the Pioneers, there follows ‘a great period of military expansion’. This is the Age of Conquests. It is characterised by 'more organised, disciplined and professional campaigns.’

Because of its success, ‘the new nation is confident, optimistic and perhaps contemptuous of the “decadent” races which it has subjugated.’ This results in ‘the acquisition of vast territories under one government’.

The Age of Commerce

But this ‘automatically acts as a stimulant to commerce,’ and The Age of Commerce that ensues is ‘marked by great enterprise in the exploration for new forms of wealth.’ He gives the example of how, ‘from Waterloo to 1914, the British Navy commanded the seas of the world. Britain grew rich, but she also made the Seas safe for the commerce of all nations, and prevented major wars for 100 years.’

‘The Age of Conquests,’ he said, ‘overlaps the Age of Commerce.’ This means that ‘the first half of the Age of Commerce appears to be peculiarly splendid.’ Decadence has not yet set in. ‘The ancient virtues of courage, patriotism and devotion to duty are still in evidence. The nation is proud, united and full of self-confidence.’

He gives particular attention to the raising of boys. They ‘are still required, first of all, to be manly—to ride, to shoot straight and to tell the truth.’ And ‘boys’ schools are intentionally rough. Frugal eating, hard living, breaking the ice to have a bath and similar customs are aimed at producing a strong, hardy and fearless breed of men. Duty is the word constantly drummed into the heads of young people.’

In the latter stages of The Age of Commerce, however, ‘gradually the desire to make money seems to gain hold of the public.’ In the Age of Conquest, ‘glory and honour were the principal objects of ambition.’ But these become ‘empty words’ to the merchant because they ‘add nothing to the bank balance.’

The Age of Affluence

Thus ‘the High Noon of the nation covers the period of transition from the Age of Conquests to the Age of Affluence: the age of Augustus in Rome, that of Harun al-Rashid in Baghdad, of Sulaiman the Magnificent in the Ottoman Empire, or of Queen Victoria in Britain.’

It is the High Noon because ‘the immense wealth accumulated in the nation dazzles the onlookers’ and ‘enough of the ancient virtues of courage, energy and patriotism survive to enable the state successfully to defend its frontiers.’ Yet ‘beneath the surface, greed for money is gradually replacing duty and public service.’

The Arab moralist, Ghazali (1058-1111), for example, complained in the declining Arab world of his time that students no longer attended college to acquire learning and virtue. Instead, they wanted the only those qualifications that would enable them to grow rich.

The change is ‘from service to selfishness’ because ‘the nation, immensely rich, is no longer interested in glory or duty, but is only anxious to retain its wealth and its luxury.’ Thus ‘it is a period of defensiveness, from the Great Wall of China, to Hadrian’s Wall on the Scottish Border, to the Maginot Line in France in 1939.’

Because money is ‘in better supply than courage, subsidies instead of weapons are employed to buy off enemies.’ And ‘to justify this departure from ancient tradition, the human mind easily devises its own justification. Military readiness, or aggressiveness, is denounced as primitive and immoral. Civilised peoples are too proud to fight.’

‘This intellectual device enables us to suppress our feeling of inferiority, when we read of the heroism of our ancestors.’ But ‘the weakness of pacifism,’ he warns, ‘is that there are still many peoples in the world who are aggressive’ - peoples waiting to burst out as pioneers.

‘Great nations,’ he warns, ‘do not normally disarm from motives of conscience, but owing to the weakening of a sense of duty in the citizens, and the increase in selfishness and the desire for wealth and ease.’ And ‘money is the agent which causes the decline’.

It ‘replaces honour and adventure as the objective of the best young men. Moreover, men do not normally seek to make money for their country or their community, but for themselves.’ And then ‘gradually, and almost imperceptibly, the Age of Affluence silences the voice of duty.’

The Age of Intellect

Following from The Age of Affluence is an ‘expansion of intellectual activity,’ which characterises ‘every period of decline.’ In the Acts of the Apostles, for example, the decline of Greek intellectualism is captured by the observation that ‘all the Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell or to hear some new thing’.

This includes ‘surprising advances in natural science.’ And ‘the ambition of the young, once engaged in the pursuit of adventure and military glory, and then in the desire for the accumulation of wealth, now turns to the acquisition of academic honours.’ He stresses that ‘intellectualism leads to discussion, debate and argument, such as is typical of the Western nations today.’

But ‘men are interminably different, and intellectual arguments rarely lead to agreement. Thus public affairs drift from bad to worse, amid an unceasing cacophony of argument. But this constant dedication to discussion seems to destroy the power of action. Amid a Babel of talk, the ship drifts on to the rocks.’

The problem, he believed, was the arrogance of the Age of Intellect in assuming that cleverness can save the world. ‘The survival of the nation depends basically on the loyalty and self-sacrifice of the citizens.’ Cleverness without self-sacrifice leads to collapse.

But ‘intellectualism and the loss of a sense of duty’ occur together in the life-story of the nation.’ He movingly describes how ‘there are times when the perhaps unsophisticated self-dedication of the hero is more essential than the sarcasms of the clever.’

The Age of Decadence.

The Age of Decadence has various symptoms:

Defensiveness

Pessimism

Materialism

Frivolity

An influx of foreigners

The Welfare State

A weakening of religion.

He also identified the main causes:

Too long a period of wealth and power

Selfishness

Love of money

The loss of a sense of duty.

As we’ve seen, one race is not outright inferior to another. But because ‘they are just different’, immigrants ‘tend to introduce cracks and divisions’. This worsens ‘the intensification of internal political hatreds’ that is another symptom of national decline.

Because of the decline in power and wealth that decadence brings, ‘a universal pessimism gradually pervades the people, and itself hastens the decline.’ And frivolity is associated with this pessimism. Let us drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die. ‘The heroes of declining nations are always the same,’ he observes. ‘The word ‘celebrity’ today is used to designate a comedian or a football player, not a statesman, a general, or a literary genius.’

Baghdad’s High Noon was in the first half of the ninth century. It was ‘the greatest and the richest city in the world.’ By the early tenth century, however, the historians of Baghdad ‘deeply deplored the degeneracy of the times in which they lived, emphasising particularly the indifference to religion, the increasing materialism and the laxity of sexual morals.’

They particularly lamented ‘an increase in the influence of women in public life.’ And this ‘has often been associated with national decline.’ The later Romans complained that, although Rome ruled the world, women ruled Rome. When confusion and violence made it unsafe for women to move unescorted in the streets, however, feminism collapsed.

The Age of Decadence is characterised by people forgetting that ‘material success is the result of courage, endurance and hard work.’ History shows this has happened in ‘almost ever possible variation of political system’. Ideas of ‘a master race of supermen’ are particularly destructive. Such delusions have inclined people ‘to the employment of cheap foreign labour (or slaves) to perform menial tasks and to engage foreign mercenaries to fight their battles or to sail their ships.’

Whereas ‘The Age of Conquests often had some kind of religious atmosphere, which implied heroic self-sacrifice for the cause’, The Age of Decadence is marked by a decline in religion — defined broadly as ‘the human feeling that there is something, some invisible Power, apart from material objects, which controls human life and the natural world’. Without this, the spirit of service is weakened, and selfishness permeates the community, weakening its coherence until disintegration threatens.

To reiterate, then, ‘decadence is a moral and spiritual disease, resulting from too long a period of wealth and power, producing cynicism, decline of religion, pessimism and frivolity.’ And ‘the citizens of such a nation will no longer make an effort to save themselves, because they are not convinced that anything in life is worth saving.’

A significant omission from his observations is the fertility rate. Not only are the citizens of a decadent nation ‘not convinced that anything in life is worth saving.’ They are also not convinced life is worth creating. Hence a declining fertility rate is throughout history the strongest sign of cultural collapse.

But he reminds us that ‘some of the greatest saints in history lived in times of national decadence, raising the banner of duty and service against the flood of depravity and despair. In this manner, at the height of vice and frivolity the seeds of religious revival are quietly sown.’

But why is this? After ‘the impoverished nation has been purged of its selfishness and its love of money, religion regains its sway and a new era sets in.’ As the psalmist put it, ‘It is good for me that I have been afficted that I might learn Thy Statutes.’

Thanks Will, fantastic read.

'No one can be the slave of two masters: he will either hate the first and love the second, or be attached to the first and despise the second. You cannot be the slave both of God and of money.

Matthew - Chapter 6 : 24